Photography is a rather simple system of recording the intensity of light either directly emitted by a light-source, or transmitted by translucent or transparent gases or bodies, or reflected in various ways by various opaque bodies. The rendering of these intensities by a photographic apparatus results in monochromatic images showing the various levels of light: with various tones of gray ranging from black to white with silver halide salts on film or paper (or with a digital sensor), or with shades of blue in the case of cyanotypes. The problem with these processes is that they do not match human vision whose cones also record the differences in wavelengths of the visual spectrum. Thanks to our sensitivity to three wavelengths/colors, which we call primaries, namely red, green and blue, and their combinations, we see the world in colors (especially under sunlight).

The first steps in the history of both silver-based and digital photography only delivered black and white images. As early as the late 1860s various ways of rendering colors were investigated. Charles Cros (1837-1888) and Louis Ducos du Hauron (1837-1920) developed trichrome processes inspired by contemporary scientific discoveries of their age (Edmond Becquerel, Thomas Young, Herman von Helmholtz, and James Maxwell): three black and white negatives would be respectively exposed through red, green and blue filters and would be used to print three layers of color pigments on top of each other, carefully registered to match. The processes were time-consuming and expensive, and the colors faded. Until the three primary RGB color filters could be incorporated either into film or on the surface of digital sensors (mostly through Kodak’s Red-Green-Blue Bayer array, or Sigma’s Foveon sensor) it was more convenient and less costly to apply colors to black and white images once they had been created. As a result, until 1936 when Kodak released its Kodachrome film (limited to color transparencies and which survived until 2009), and the 1960s when the progress in color negatives and papers allowed for better color reproduction and increased light sensitivities, black and white photography reigned—which leaves us now with huge amounts of photographs, especially archives, that are deprived of colors.

Colorizing black and white photographs started as early as the first years of the daguerreotype process in the 1840s. With the current progress of digital image-processing software and artificial intelligence colorizing images just gets faster, easier, more precise. We can see a near future where anyone will be able to upload a black and white image and get it exactly colorized once the materials, people, landscape and objects will have been checked according to the time they were photographed with a huge on-line database of their colors. However, eyebrows were raised when people who were not the author started to colorize the photographs without his or her consent. One of the first historical examples of problematic colorization was the 1947 movie Casablanca. After buying the rights to this classic, Ted Turner decided to release a colorized version of it in 1988. The film critic Robert Ebert (Chicago Sun / Times) summarized his experience after viewing the movie: “Colorization does not produce color movies, but only sad and sickening travesties of black and white movies […] that is little more than legalized vandalism.” [https://www.rogerebert.com/interviews/casablanca-gets-colorized-but-dont-play-it-again-ted]. More recently, in 2019, in the April 17 edition of the web media forward.com, journalist Naomi Zeveloff wrote a whole article dedicated to the colorization of the concentration camp mug shots of a young Polish girl, Czesława Kwoka, a victim of Nazi extermination policies, by Brazilian colorizer Marina Amaral: “Should We Be Colorizing Photographs from Auschwitz?” The “work” was actually signed Marina Amaral, the colorizer, and had been shared on-line by the Auschwitz Museum on its Facebook page (still there on June 20, 2020). Zeveloff commented: “But as gripping as I found the colorized picture, I had a gut-level disagreement with the premise of the Faces of Auschwitz project — that photographs from the past should be manipulated to appeal to people in the present. […] I did see the project as distorting history.” She then quotes Larry Gross, a professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism arguing that “ there was no “artistic intent” with the black and white photos in the Faces of Auschwitz project. If the Nazis had the capacity to photograph inmates in color, they would have done so.” Hmmmm, to this I would answer that 1-the Nazi could have used color if they had wanted, Leni Riefenstahl had done it for the 1936 Berlin Olympics; Agfa color film existed at the time and they probably had access to Kodachrome (or its then competitor in the USA, Ansco/Agfa), 2-these are historical documents and any alteration can be considered highly problematic (as George Orwell had already warned in his 1984 novel: who controls the past [and its imagery], controls the future).

Since the early 2000s, various image-processing software and artificial intelligence have been coming to the rescue of the colorization of such black and white film and photographs. A new generation trained in the graphic arts with such programs as Adobe’s Photoshop or Illustrator has taken upon itself to colorize our past for the spectacle of it, “our pleasure,” and in order to glean some financial or exposure reward (and sometimes both). However interesting, enticing and spectacular, these operations might be, they also raise several issues: historical accuracy of colors, value of the created images (still documents or just spectacular entertainment?), respect of authorship, ethics.

1- COLOR: How accurate are these colorizations? If some show an excellence at their craft supported by meticulous research, others, either perceived as lazy or “creative,” are taking shortcuts as well as liberties with reality and history. These bring us to other deeply disturbing issues as follows.

2- HISTORY: Are we losing the documentary/historical value of those black and white photographs and will the next generations contemplating those colorized versions take them as granted primary sources, in other words as trustable documents? Will those colorized images cease to be reliable historical documents after being manipulated in such ways (and to what extent)?

3- INTENTIONS: Whatever these might be they cannot but be ambiguous, all the more when the colorizers sign photographs taken by others with their own names. The colorizers, even though they apply their copyright to those images, are not the authors who are the only ones that can / could authorize the modification of their work (“intellectual right,” as stipulated in the Bern convention)—I am not sure that photographers such as Margaret Bourke-White, Walker Evans, or Dorothea Lange would agree with anyone plundering the archives of the Library of Congress, colorizing their photographs made for the Farm Security Administration in the 1930s, and signing them with their names—as if the editor of a book, or worse a news article would somewhat modify the size of the fonts and their color (according to content of course), and sign the modified texts with her/his name!

4- COPYRIGHT (different from unalterable “intellectual” rights protecting authorship): In order to circumvent the copyright conundrum most “colorizers” dig into public archives (Library of Congress, New York Library, army archives) choosing works whose copyright has elapsed (roughly 70 years after the authors’ death—if after 1978, or 95 years after their first publication), or works which are “work for hire” commissioned by a public entity, in which case the copyright belongs to the commissioner, the public entities, and thus to the public. One issue that becomes highly problematic, if not highly unethical, if not illegal, is when the colorizers sign the colorized photographs with their names (and sell them or use them to advertise their colorizing businesses)… as if I painted Rodin’s Penseur or Balzac, and signed it with my name. All right, there are probably, somewhere, even in the shops of reputable museums, 6-inch-tall highly colorful plastic reproductions of these works… I am not saying that it is good taste, that I would not tolerate such reproduction for any somewhat entertaining or obscene work by Jeff Koons (who would definitely ask for royalties), I am just venturing the argument that it is questionable… and this while colorizers, free colorizing websites, the publications of colorized photographs (on Instagram or Pintarest) abound.

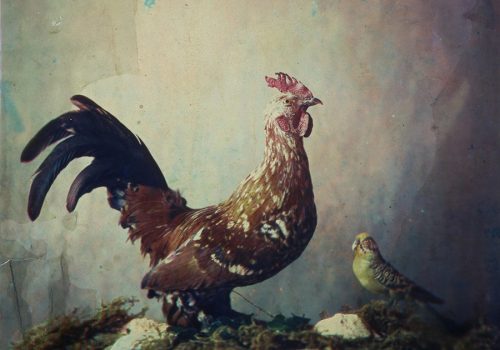

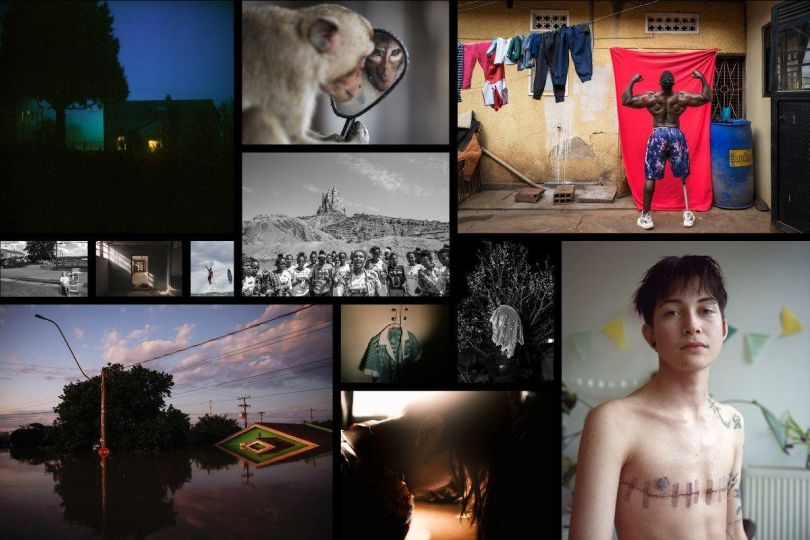

In order to push the argument further, I have myself colorized some photographs here displayed. They have been the previous victims of many colorizers. I have even “re-colorized” some of their colorized works… and I would never go as far as signing them with my copyright except (here for one of my own black and white photographs (Notre-Dame bridge and pigeons) colorized through one of the many on-line colorizing software to illustrate this article). The ones that I have not re-colorized and that I am just quoting carry the copyright mentions of their colorizers (Marina Amaral, Danna Keller, Jordan Lloyd/Dynachrome, Mads Madsen, Richard James Malloy… ).

Bruno Chalifour