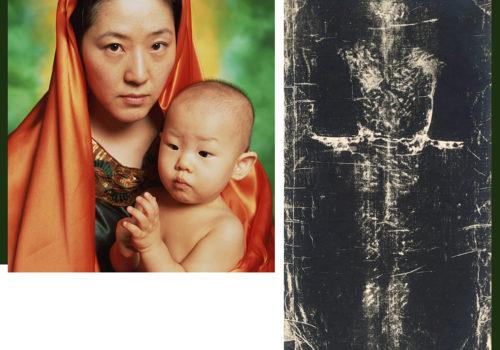

This is the 36th dialogue of the Collezione Ettore Molinario. In order to celebrate the third year of “encounters” I wish to introduce you to images that might seem furthest from my gaze, a Madonna with child by Andres Serrano and the Shroud, guarded since the sixteenth century in the Cathedral of Turin. They are sacred presences that tell tales of faith, of believers, and of the unshakable faith in the strength of images, no matter what.

Ettore Molinario

It is a simple intuition, a mother and her son. And the bond that links them in the news of every day, of all times and in the whole world, becomes the story of the mother and son of God. An image that passes from the earthly dimension to the otherworldly one, from news to faith. This is the miracle of Christianity, which anticipates by eighteen centuries the miracle of the photographic image and of the faith it has fuelled ever since. It is also the theme that Andres Serrano has been investigating for forty years. At the time he created the Holy Works cycle, to which La Chinoise Madonna belongs, Serrano, who was born and bred in a devout Catholic family, had already signed, as a young blasphemous artist as many consider him, his Piss Christ, the famous crucifix immersed in urine. Twenty years later the reflection softens, a friend of Andres and her son become the Virgin and Child. Small variations: mother and son are Chinese from Brooklyn, and the blue veil that envelops the Madonna, a prefiguration of the vault of heaven, is instead orange, a color sacred to Buddhism. Yet the message gets through, it transcends everyday life and becomes a symbol. The success of a religion that makes everyday life its message.

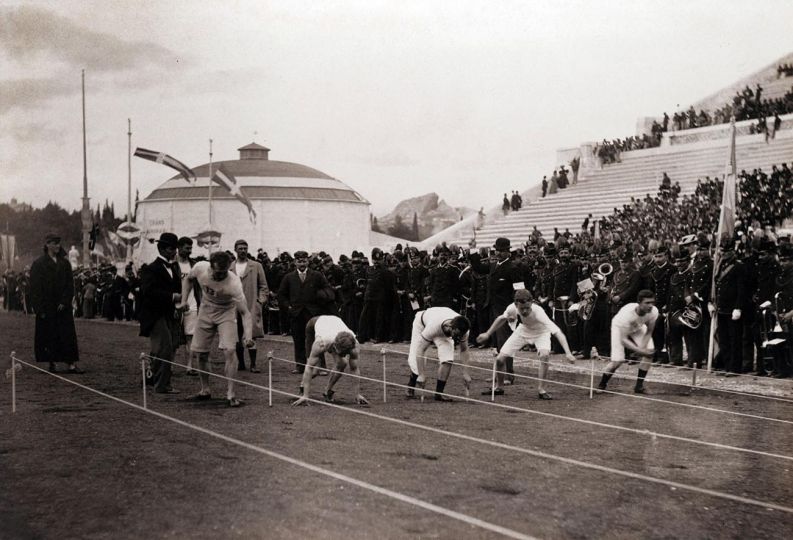

If a son is born, the son becomes a man and every man is destined to die. Respecting the “photographic” nature of its story, Christianity completes the life cycle of Jesus in the most extreme and spectacular of images, the most organic and the most sublime, the most scientifically false and the truest because the heart of every believer is always in search of proof that confirms the divine word. Faith and believer are the terms of the problem. And if we talk about Christian faith and a “faithful” image, of a copy of the truth and the revelation of the truth, then we talk about the Holy Shroud.

The linen sheet, that’s the meaning of the word “shroud”, arrived in Turin in 1578. Certainly that cloth, over four meters long and more than one meter wide, wrapped the body of a man, tortured and crucified. No one can say whether it is the body of Christ, but the correspondence with the Gospels is precise. When the Shroud was exhibited to the public in 1722, a foreign ambassador noted the presence of over one hundred thousand believers. None of them had any doubts. And to ensure that no doubt was ever raised in the future, on the 29th of May 1898 the lawyer Secondo Pia, an amateur photographer from Turin, obtained permission to photograph the extraordinary relic for the first time. On the cloth, as if it were a photographic negative, Pia discovered a body, and above all a face, imprinted. By the way, the medieval world already knew the Shroud, but no one had raised the question of its authenticity, those who wanted to venerate it as the portrait of the son of God were free to do so, and equal respect for those who did not feel the need for such a tangible proof. The nineteenth century, the positivist era of the negative-positive process of photography, changed the temperature: since photography “revealed” the face of Christ, that face is authentic.

In 1931 Secondo Pia’s shots were followed by those of Giuseppe Enrie, which were more precise, not only because Enrie was a professional, but also because at the time the materials were more sensitive. So in 1978, the scientists of the STURP, The Shroud of Turin Research Project, arrived in Turin from the Los Alamos laboratories of New Mexico, directed at the time of the Second World War by Robert Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb. Among them is one of the most famous scientific photographers of the time, Barrie Schwortz, who shot the Shroud and created perhaps the most dramatic images of it. The back is striking for its symbolic power, almost fetishistic in the traces of the whippings, and it is with this charge of earthly pain and pleasure that the Shroud enters Ettore Molinario’s collection. But this sacred image also brings its doubts and uncertainties to the collection. Where does faith in images lead us, to illuminate our path or to lose it? What if every photograph, loved, sought, recognised and collected, was our personal, very fragile Shroud?

Ettore Molinario

DISCOVER COLLECTION DIALOGUES

https://collezionemolinario.com/en/dialogues