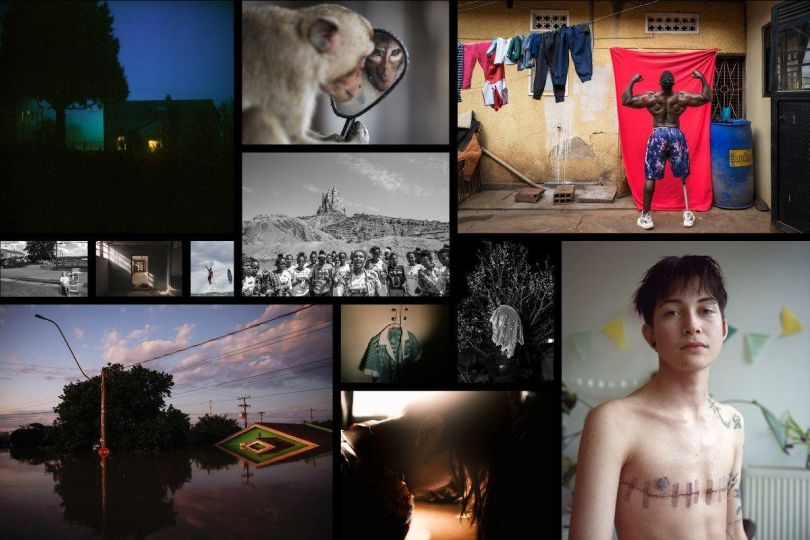

This is the nineteenth dialogue in the Ettore Molinario Collection. Perhaps an extreme encounter, as such is the life and work of Pierre Molinier, an author I love very much and it is no coincidence that his Shaman is the tutelary deity of my collection. Alongside this artist, who is so very modern in his intuitions on gender identity, is the portrait of the «Inconnue de la Seine», signed by Albert Rudomine. A game of masks, of life and death, and an invitation to approach fetishism with a smile of gratitude.

Ettore Molinario

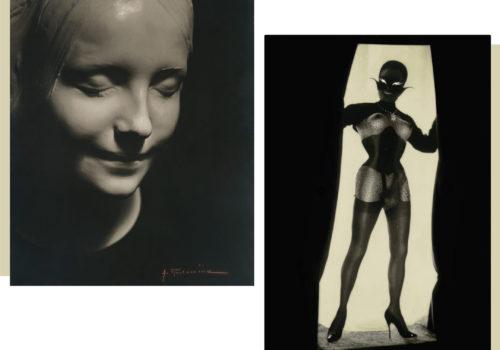

They had laid her on a black marble bed and exhibited her in the large window of the Paris morgue, on the Quai de l’Archevêché, in the hope that someone would recognise that young woman, fished out lifeless from the waters of the Seine. But despite the crowd that gathered in front of the morgue, the destination of the Sunday walk at the end of the nineteenth century, no one had claimed her body, no one had given a name to her still intact face and her inexplicably smiling lips. Such a delicate smile, as if the girl, who committed suicide, had glimpsed a light beyond the darkness and had brought back a message of bliss to the living.

The first to be moved by the mystery of this beauty is the medical examiner’s assistant who instructs Michel Lorenzi, originally from Lucca and emigrated to France around 1870, to take a cast of her face. Shortly after, the death mask is exhibited among the masterpieces of sculpture in the atelier window, at 19 rue Racine, and there it remains anonymous until, in 1900, Richard Le Gallienne describes it in the novel L’Adorateur d’image. In 1902 Rainer Maria Rilke, then engaged in drafting the biography of Auguste Rodin, passes in front of the same address, it’s love at first sight and that siren from beyond the grave enters one of the most famous works of the German poet, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. The book ignites passion across Europe.

In the spell of the «Inconnue de la Seine», as Vladimir Nabokov baptised it, other famous victims parade at a macabre dance rhythm, André Breton, Alberto Giacometti, Salvador Dalí, Picasso, Man Ray, Louis-Ferdinand Céline and in 1927 Albert Rudomine who portrays the «Mona Lisa of Suicides», according to the definition by Louis Aragon, using the same lights with which in the studio he illuminates the faces of the actors and later the sculptures of Rodin.

Yet none of these characters, however assiduous of other dimensions of reality, dreamlike and frightening as they are, agree to truly join the mystery of the Unknown and her mask. Too dangerous perhaps, and the words of Maurice Blanchot are useless when he imagines that «that teenager with her eyes closed died in a moment of extreme happiness». We must therefore wait for Pierre Molinier, the shaman Molinier, the man-woman, for that plaster cast to breathe again and to transform itself into the most authentic face of the artist, in his feminine double, which emerges from the deep waters of the ego and completes the perfect androgyny of the body. Legend has it that the artist at eighteen, in 1918, photographed his sister Julienne, who died of Spanish flu, also beautiful and a virgin in the white dress of her first communion. Molinier had locked himself in the wake room and lay down on that lifeless body, had enjoyed, had spilled his sperm, and those drops were «the best of me», a fraternal gift for Julienne to enter, she too happy and content, in the realm of the dead. After all, that necrophilic fantasy was just another smile, a dedication to lovers of fetishism, the only ones, like Pierre Molinier himself who would take his own life in 1976, capable of transforming death into the most extreme pleasure.

Ettore Molinario