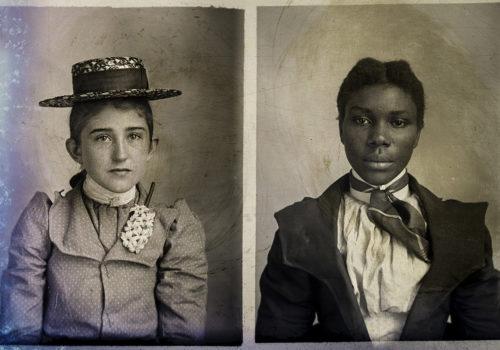

Hugh Mangum (1897-1922) was an American itinerant photographer who worked in the Southern states during the rise of the Jim Crow era laws mandating racial segregation and discrimination. His clientele was both racially and economically diverse.

Through Mangum’s lens, we witness a varied citizenry whose unique personalities and essences Mangum has captured, redefining our sense of history and of place and time. After his untimely death at age forty-four from influenza, the glass negatives from his Penny Picture Camera lay abandoned and unprotected in a family tobacco barn, largely forgotten for fifty years. In the 1970’s, a developer was moments away from bulldozing the barn, and it was only through the concerted efforts of local preservationists that they were saved, and later donated to Duke University.

A limited edition of photographs by Hugh Mangum is now available, as selected and printed for this exhibition by Alex Harris, photographer, writer, and a founder of the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke, and Margaret Sartor photographer, writer, and instructor at the Center. This exclusive edition shows the genius of Mangum, the alchemy of time and the elements, and the unique vision brought to this project by Sartor and Harris.

The exhibition, which first opened at the Nasher Museum in North Carolina, followed by exhibits at ACA Galleries in New York, and the Deland Museum, Florida, is now available for touring. It is accompanied by the premier edition of the book, Where We Find Ourselves, authored and edited by Sartor and Harris, who are interviewed here.

Touring Exhibition contact: Patricia Lanza ([email protected])

Book sales: Where We Find Ourselves, 2019 ,

https://www.amazon.com/Where-Find-Ourselves-Photographs-Documentary/dp/1469648318

Limited edition Prints: MB Abram

https://www.mbabram.com/hugh-mangum-overview)

For an inquiry email: [email protected]

Lanza : Discuss Hugh Mangum and how you came to the project?

Harris and Sartor : As an itinerant portraitist during the rise of Jim Crow segregation, self-taught photographer Hugh Mangum welcomed people from all walks of life into his temporary studios. After his death in 1922, hundreds of his black-and-white glass plate negatives, with over 12,000 images remained stored, and largely ignored, in a tobacco drying barn on his family farm in Durham, North Carolina. Slated for demolition, the barn was saved at the last moment, and with it this unparalleled document of life at a turbulent time in the American South. We first encountered his work when it was donated to Duke University in the late 1980s, but it was only in the 2000s, with the aid of digital technology, that we began to grasp the true scope and originality of Mangum’s artistic achievement.

As photographers and scholars of photography, we have long been fascinated by the ways in which photographic portraiture, from its earliest days, has served as an indicator of personal identity, social status, fashion, cultural traditions, relationships, and history. The great variety of portraits Hugh Mangum made reveal a time and place that we, as Americans, think we are familiar with and have many assumptions about—ideas we carry with us about race, class, and family relationships, ideas based in fact but also, to a degree, in fiction. What these images convey is both profound and surprising.

Perhaps what is most surprising about Hugh Mangum’s work is its artistic freshness. The portraits collected on his multiple-image glass plates were never intended to be viewed as a group but seen in the twenty-first century they allow us to witness what the photographer experienced on a daily basis. Mangum’s portraits reveal the open-door policy of his studio and the racial and economic diversity of his clients. Some of Mangum’s sitters are marked by notable influence, others by scarcity, but all are imbued with a strong sense of individuality and often joy, suggesting the sitters constructed their own visual narratives in collaboration with Hugh Mangum.

As editors we were drawn not only to the originality of the portraits, but also to the way that these portraits had been altered by and survived, both literally and figuratively, the passage of time. Indeed, these dazzling images — made even more dazzling by the work of time — are a celebration of life.

Lanza : What is the significance and meaning of the publication title: Where We Find Ourselves?

Harris and Sartor : Where We Find Ourselves was a title we chose early in our process because it is at once a compelling metaphor, a question, and a statement of fact. In looking at Hugh Mangum’s striking photographs created during a tumultuous period in the American South, we found ourselves confronting and rethinking much of what we’d been taught about the past and the handed-down assumptions we carry with us still. Mangum’s instinctive ability to connect with his sitters is palpable even now and the portraits he made act as a kind of portal between past and present. They hint at unexpected relationships and histories, create a new way of connecting the known and imagined past of the racial divide. Seen, understood, and experienced now, in the present, they prove how fantastical, how imaginary—how delusional—is the world conjured into existence by the racism of white supremacy. These photographs contain an implicit message that we must redefine our ways of looking at one another today.

When curating the exhibition, we experimented with scale: significantly enlarging a selection of portraits, sometimes to life-size, to create not only a sense of looking directly at the men, women, and children who sat before Mangum’s camera, but also of these individuals looking back at us. And we feel strongly that our choices around damage, color, and scale are utterly consistent with the paradox of timelessness and timeliness that makes Mangum’s art both durable and relevant.

Lanza : What was your curatorial and editorial vision, interpretation, and process for the exhibition and the book?

Harris and Sartor : Our approach to these century old glass plate negatives was a highly personal one. There were two key decisions that helped define how we selected images and which ones. The first was our recognizing that the high-resolution scans allowed us to scrutinize and enlarge individual portraits from the multiple image glass plate negatives. This meant looking at some 10,000 or more individual exposures, which was time consuming but enormously exciting and allowed us to choose the specific portraits that most moved us. The other choice was embracing not just the artistic gifts of Hugh Mangum but also that the glass plate negatives had survived a history of their own. We were surprised and moved by the poetic power of the damage that had occurred to Mangum’s negatives over time and decided to reveal that damage as we printed his negatives. The photographs in this exhibition and book are evidence of something astounding — the unpredictable alchemy that often characterizes the best art and its ability over time to evolve with and absorb life and meaning beyond the intentions or expectations of the artist.

Where We Find Ourselves speaks as much to the nature of art as it does the life and vision of Hugh Mangum. His portraits weren’t widely known in his lifetime; only now, nearly a century after his death, are they receiving serious attention. The same is true of other photographers, some of them among the greatest practitioners of the medium, such as E. J. Bellocq with his Storyville portraits from New Orleans; Richard Samuel Roberts and his beautifully crafted portraits of African Americans in South Carolina; Mike Disfarmer’s starkly realist portraits from Heber Springs, Arkansas; and Vivian Maier’s vast body of work made on the streets of Chicago and New York.

Lanza : Discuss the preservation methodology for these historical works and your choices for the book publication?

Harris and Sartor : The prints in this exhibition were made from digital scans of black-and-white, dry glass plate negatives exposed and processed by photographer Hugh Mangum at the turn of the twentieth century. When Mangum died in 1922, the glass plates remained in the family’s barn for five decades, subject to the vagaries of time, weather, and disregard. When in the 1970s,they surfaced and were donated to Duke University in 1986. Mangum’s glass plates were then professionally cleaned and stabilized by highly trained conservators. In the 2000s, they were photographed in high-resolution color with a digital camera.

Hugh Mangum’s dry glass plate negatives have a history of their own etched and infused into their emulsion, a latent image fully visible now because of our decision to reproduce his work in color rather than gray scale. A century later, enriched in meaning and made more hauntingly beautiful by the effects of time’s passage, they surfaced in a world that had also changed. The original black-and-white glass plate negatives, seen now with their damage and decay fully visible, reveal portraits that are surprisingly vibrant; the cracks, fingerprints, and delicate color shifts that surround and sometimes cover the sitters’ faces give them new meaning.