The Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris is featuring an exhibition of the 2015 HCB Award winner: an oeuvre spanning twenty years of a dune wanderer.

At first glance, one might be led to believe that Claude Iverné is a photographer. While it is true that he expresses himself through images, he rarely thinks or speaks of himself in terms of photography. He is a vagabond, an ethnologist, an archivist, and a curious observer rolled into one. And an artist to boot. “A poet,” adds Quentin Bajac, Chief Curator of Photography at MoMA. Over time, covering his tracks and refusing to follow a straight path has become second nature to Claude Iverné. Or, better, he imperceptibly puts the viewers on the trail, letting them find their way in on their own. This is also the approach adopted in the exhibition at the Fondation Cartier-Bresson. Visitors are invited on a treasure hunt across Sudan, a country one only ever talks about in reference to humanitarian tragedies, and which we discover here in a marvelous new way, through twenty years’ worth of travel. The itinerary takes us to a certain level, and it’s up to us to go further and get to know this or that individual, building, or stretch of land. That’s the idea, anyway. The photographs are just an incentive.

Like lines of poetry, Claude Iverné’s photographs need to be read several times before one can unlock their meaning. For the most part, they are black and white, tinted in an odd shade of grey, as if filtered, not unlike old-fashioned images, for example nineteenth-century photographs, in which other explorers trekked across Sudan. “Claude Iverné’s photographs,” commented Quentin Bajac, “make me think of those who, around that time, traveled up the Nile to the First or Second Cataract, if memory serves: Francis Frith and Maxime Du Camp.” Beautiful to look at, refined and subtle, taken together, these images compose a journey across Africa and among its peoples, depicting them with attentiveness, respect, and dignity. There are portraits of men and women, views of their homes and of the surrounding landscapes — mountains, deserts, pyramids; there are pictures of animals, trees, objects, and elements — rocks, sand, and the wind; and there are cities, too: an ode to the richness and diversity of that land.

Claude Iverné is interested in everything, whether alive or half-forgotten; he pays attention to others, but without pity or pathos. Rather, what matters here is distance — among other things. “I love slowness,” he said. “I could stay forever contemplating a single view, reading a single phrase, letting my eyes wander across a single picture. It is said that Sudanese patience knows no bounds. I found there was room enough for my slowness, or at least enough to rediscover real life, contemplate, let go of the destructive productivity of our developed world. My friend Hafez reprimanded me once. We were riding on the back of a pickup truck at ten miles an hour — an ideal setting to observe and move forward at the same time, a bit like on the back of a camel, but more comfortable. From time to time, we’d stop to take a better look. We were supposed to get to Sedeinga before sunset. For hours, every Nubian we encountered had been giving us the same distance and the same travel time to our destination. ‘None of them owns a watch, knows how to use a computer or drive a car, or has ever seen a map. How can you expect them to express themselves in a way you are accustomed to, using your system of reference?,’ Hafez asked me.”

Claude Iverné offers us a new vision of the African imaginary, devoid of stereotypes and in stark contrast to the aesthetics habitually adopted by news reporters. Christophe Ayad, a journalist for Le Monde, wrote in 2012: “More than a difference, there is an abyss between photographing Africa and photographing in Africa. It’s not a question of syntax, but of the point of view. Claude Iverné, for example, photographs in Africa, that is to say, at the human level, as an equal among equals. It may seem straightforward, but in fact it calls for a sustained effort at shedding deeply ingrained prejudice and stereotypes before they are reproduced in black and white. Darfur is a region Iverné knows well: he had visited it before the conflict officially erupted. ‘A permanent war was going on,’ recalls Iverné, ‘guns were everywhere, but no one talked about it. In late spring 2004, when the ban on international journalists was finally lifted, the major clashes were already over. Both the humanitarians and the journalists were somewhat disappointed. There wasn’t much to show: no emaciated children, no fighting.’ Photo reporters who went there to compete with Sebastiao Salgado and his iconic images of the biblical famine in Ethiopia in 1984, found themselves reduced to an exercise in style. Claude Iverné evokes an image by the renowned war photographer James Nachtwey that shows a close-up of an old man’s face with a single tear rolling down his cheek. ‘What information does it convey?’ ” In the work of Claude Iverné, the drama is present, but it is invisible to the naked eye: it’s the absence of the healthcare system and schools, the absence of land ownership and harvests. “I am on the side of the free will. I announce more than denounce. Have war photographers ever put an end to war?” Violence persists: muted and subterranean. How do we recognize it? The plain portrait of an old man in the middle of a field that no longer looks like fertile land says it all.

For Claude Iverné, Sudan is a personal matter. It is tied to his “second father — since he hardly knew his first one — who dreamed of traveling the Forty Days’ Road, named after the length of time it took slave and merchandise caravans to reach Egypt from the provinces of Darfur and Kurdufan (east-central Sudan, straddling Northern and Sub-Saharan Africa). “I remember very clearly how I first set foot in Zamalek in Cairo,” he recalled. “I came to the Apostolic Nunciature in 1997 to access the original documents pertaining to the expedition of the missionary Daniel Comboni. The idea was to follow the Forty Days’ Road, on the trail of camels herded from Darfur to Asyut and then on to markets in Cairo. Back then, caravans would reach the Nile at the level of Daraw in upper Egypt. I stayed there for a few weeks in 1998, to understand how things worked. Local Sudanese would offer me the hospitality of their homes. Siddik said to me, ‘I am going to embark at Khartoum on February 4, and head to Fasher to round up a train of camels and put it on the Forty Days’ Road…’ I believed him. On February 4, 1999, I found him at the departure gate hardly surprised to see me. We waited together all day for the plane to come.”

A nomad at heart, the Frenchman likes to compare himself to a domestic animal, an androgynous camel in a herd of dromedaries. He is the fox who asked the Little Prince to tame him and wept when they were saying goodbye. Iverné evoked his friend Hafez, “a riddle wrapped in an enigma.” Illiterate, Hafez served as Iverné’s translator from the very start. Both men were very intuitive. Hafez was a living proof of universal education. “When I cannot express myself directly in one dialect or another, or even in Sudanese Arabic,” explained Iverné, “[Hafez] would instinctively find simple Arabic words and images corresponding to everyone’s linguistic level. In 2004, Doctors Without Borders sent me to nomadic tribes to help them communicate during a vaccination campaign. The convoy passed right in front of Hafez’s camp just as he was saddling two horses. ‘I heard you were in the area, so I came looking for you!,’ he exclaimed.”

In 2015, Iverné won the Fondation Cartier-Bresson Award for his project, which was yet to be developed: a true sign of recognition. According to Quentin Bajac, a member of the jury, “Claude Iverné belongs to the movement which, since the 1970s, has been thinking of new ways of expressing the contemporary world and its issues.” The photographer was supposed to return to Sudan and continue his exploration. But Sudan is a land fraught with danger. In the south, it’s been said, there is a narrow line between dream and nightmare. And, as Cartier-Bresson used to do, one shoots first and asks questions later. While the south of the country is plagued by historical problems, twenty-first-century issues also come into play, and money rules all. Although he was supposed to go back to the region in the fall of 2016, as per conditions of the award, Claude Iverné decided not to, mainly because of his daughter Camille who is about to turn ten. In November, around the corner from his apartment at Boulevard de Strasbourg in Paris, he admitted: “There is no prize worth the sacrifice. As Brassens sang, ‘Die for ideas, all right, but make it a slow death.’ When I announced to my daughter on the eve of my departure that the plane headed for Juba would leave without me, she came up to me with her eyes closed and just hugged me without saying a word.”

In the end, it doesn’t matter: the work already accomplished is enormous. Iverné completed it with portraits of Sudanese expats and refugees in Europe. They figure in the eponymous catalog accompanying the exhibition, Bilad es Sudan (“Land of the Blacks”), published by Xavier Barral and containing the full set of images. Prior to this publication, Claude Iverné authored a three-volume set entitled SudanPhotoGraphs — seemingly incomprehensible, soft-cover pamphlets that, upon closer look, turn out to be very comprehensive. Made up of notebooks of varied layouts, filled with photographs, maps, personal notes, anecdotes, these books resemble travelogues: everything is focused on the need to slow down and question what’s in front of you.

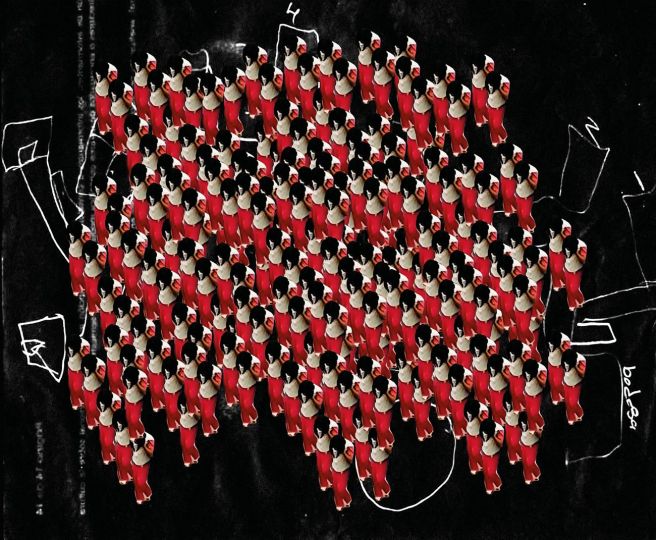

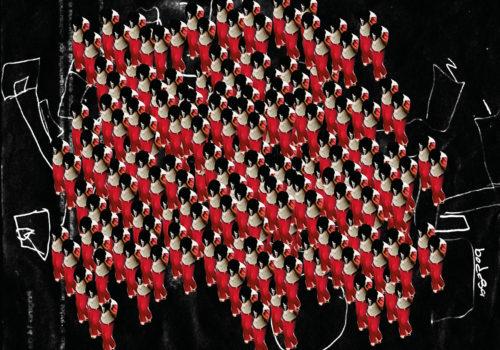

Claude Iverné may be a poet, a man of letters, and a bit of a bohemian, but there is also an archival dimension to his long-term work on Sudan which is both topical and historical. He has a way of cataloguing people and things that is evident in his bricolage of portraits of Sudanese men and women, which slightly resembles a high school yearbook. This is a much more pragmatic dimension than he is willing to admit, and it is evocative of another famous photographer. “There is a sense of precision in Claude Iverné’s work,” noted Quentin Bajac. “To say that his images require close attention makes me think of some of the greatest photographers. Claude Iverné might feel overwhelmed by the comparison, but one could mention August Sander, for example. A number of images by the German photographer have also become iconic, while at the same time are not easy to interpret: they require a fairly good understanding of Germany at the time to be fully appreciated, since they often hinge on details or prevalent stereotypes. In Claude Iverné’s photographs we find the same kind of precision and attention to detail, which, depending on one’s knowledge of the place and its history, lends itself to more or less subtle interpretation. Like Sander, Claude Iverné incites the viewer to summon a certain knowledge to enrich one’s experience of the photographs.”

His unusual style, subject, and refusal of any classification make Claude Iverné a sort of a rebel in contemporary photography. One could even say he is political. He expresses some reservation: “To me, politics means proposing an alternative to mindlessness and brainwashing. Only too often do I hear that one must cater to the public, do some hand-holding, explain everything… As if the public were a formless mass devoid of any living resources. I continue to think that art can be a bastion against market forces, even if the artist get lost in the grind.”

Iverné asserts intellectual autonomy and calls for “a struggle, a permanent effort to combat mindlessness.” When he was a child, coming home from school one day, his mother said to him, “The fact that you think differently than everybody else doesn’t mean you’re wrong.” She paused and added: “… but it doesn’t mean you’re right, either.” Today, he spends his free time reading philosopher Jacques Rancière and indulging in boredom indispensable to every thinker. The Ignorant Schoolmaster is among his favorites, a book that revives the memory of a singular character in the history of education — Joseph Jacotot — and raises the fundamental political question of equality. His influences also include T.E. Lawrence’s introduction to The Seven Pillars Of Wisdom; The Little Prince; Hayao Miyazaki’s film My Neighbor Totoro; correspondence and interviews of Walker Evans; Arthur Rimbaud; Eugene Delacroix’s journal; Charles Baudelaire art criticism; Alberto Giacometti’s writings; as well as Henri Matisse’s writings on art. His other passions include collecting found objects in the street, pieces of trash flattened on roads and highways around the world, dry leaves gently preserved for decades, and a collection of seeds of trees planted secretly here and there.

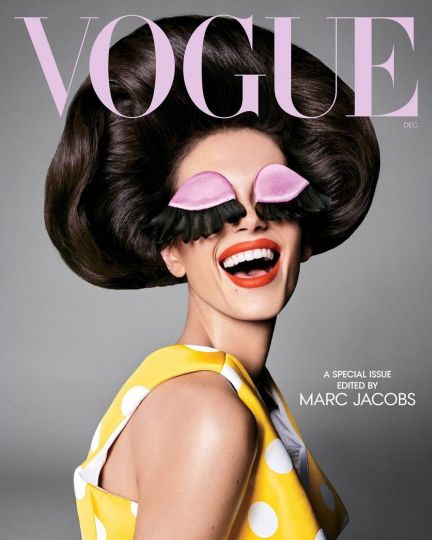

As strange as it may seem, before becoming an African explorer, Claude Ivenré was a commercial fashion and portrait photographer. His images were very toned down, not unlike his Sudanese photographs, but perhaps more aestheticized and enhanced with feminine beauty. He has some memorable anecdotes about that period in his life, about New York and Alexander Liberman, the editor of Vogue.” I once wrote a note to Alexander Liberman after having read an uplifting interview in which the director of Condé Nast said that talent wasn’t enough for an artist to break through. He got out of his limousine and, with a beautiful woman on each arm, majestically stepped into an Upper East Side gallery that was holding a painting exhibition. I blocked the procession and handed him a small envelope. I saw him the following day, but later on, because of a commission from [the mail-order company] 3 Suisses, which took me back to France, we lost touch.”

Now the time has come for this Burgundy native, aged 54, to enjoy success with an exhibition, a book publication, and the resulting acclaim. A friend asked him about the depression that often accompanies accomplishment. Claude Iverné said he couldn’t complain about a lack of projects. “Never having owned a TV set, I once caught a snippet from The Lord of the Rings just as the small creature with big pointy ears says to the hero: ‘All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.’ I know that, down inside, I fear that once I withdraw into the desired seclusion, I won’t even have the time to be bored.” He has one book in the works, on Rashid Mahdi, a Sudanese photographer, writer, and filmmaker, and another of his fascinating encounters. There is also a project for a second book on the history of photography in Sudan; an idea of a photographic herbal; and the desire to start a liberal school where everyone learns whatever they want. But before all that, there is a wonderful exhibition at the Fondation Cartier-Bresson composed of images, texts, and sounds. To see it the way it is intended to be seen, one must awaken the ox within and become a curious explorer.

Jonas Cuénin

Claude Iverné, Bilad es Sudan

May 11 to July 30, 2017

Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

2 Impasse Lebouis

75014 Paris

France