Photographer of de-industrialization, socially engaged lecturer

Born on the Isle of Man, halfway between Ireland and the UK, Chris Killip decides to become a photographer at the age of 18. He moves to London where he becomes an assistant to the advertising and portrait photographer Adrian Flowers (1926 – 2016).

Around 1969 he radically changed course; he focuses on the reportage & gallery owner Lee D. Witkin was one of the first to recognize his talent: he prefinances a portfolio. During the day he portrays his own community on the Isle of Man, at night he works in his father’s pub. This is published in The Isle of Man: A Book About the Manx.

At the same time, it establishes his reputation, he is commissioned to photograph Huddersfield and Bury St Edmunds for a project Two Views-Two Cities. It is a visual confrontation between an industrial and a rural community.

Killip moves to Newcastle in 1973 and continues to live there for the next 15 years. Northern England is the industrial heart of the United Kingdom. It is precisely during this period that a radical transition takes place, which Killip describes as de-industrialization. Coal mines are closing, steel companies and heavy industry disappear, the economy is globalizing.

The shipbuilding companies of Tyneside (the greater Newcastle area) triumphantly announce that they will build the largest tankers, not realizing that they are the last they will build. Unemployment marks the population; poverty and the survival economy are becoming a daily occurrence. For Killip there is no doubt who he photographs, it does not even occur to him to answer the “who’s side are you on”, it is self-evident. He is not always appreciated: the raw images are read by the social authorities as an accusation of their approach.

He also roams further along the coast. In Lynemouth, Northumberland, he meets a community of Travellers (a roaming community)s who live from the recovery of coal from the sea. That coal was discharged by a power plant and a coal mine. Killip invests six years to gain the trust of the people. When he finally started shooting there, it dawned on him that “the place confounded time; here the Middle Ages and the twentieth century intertwined”. The result is the Seacoal series.

A little further along the coast he discovers Skinningrove, North Yorkshire, a village where people work in the steel mill but also practice fishing. The Skinningrove series shows the men whose dignity is linked to the work on the water and the rhythm of the sea. But that sea is inexorable, it takes the lives. One of the most heartbreaking images shows a trembling boy being taken out to sea a few weeks after his father drowned ” so that he would no longer be afraid of the sea”.

A selection of images from the 1973-1985 period from Newcastle, Tyneside, Seacoal and Skinningrove are published in Killip’s best known work: In Flagrante (1988). Killip is acclaimed in the UK and abroad, and in 1989 he received the Cartier Bresson Award.

It is ultimately in the US that he received full recognition. In 1991 he started teaching at Harvard as a professor of visual and environmental Studies, a post he held until 2017.

Killip is again in the public eye with the retrospective exhibition Arbeit / Work in Folkwang (2012, Germany). It shows an overview of his work in the period 1969-2005.

In recent years he re-organized his image archive, but it is his son who drew his attention to several series that Killip had not looked at again after the publication of In Flagrante. Images of raves e.g. in the punk club The Station, images of the shipyards. This results in the publication of 4 magazines Skinningrove, The Station, Portraits & The Last Ships in 2018.

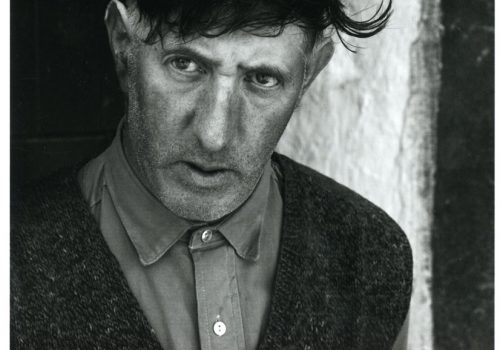

Killip died on October 13 from lung cancer. He is not really known by the general public but is revered as one of Britain’s greatest photographers by his peers. His images appear cold observing due to the use of the 4×5 inch camera. The most important thing Killip taught us is the method, the approach: he doesn’t work as a reporter, on the contrary he photographs a community from within. He is not experienced as a stranger, but as one of them, an equal. He also emphasizes that he does not want to convince, and he isn’t a historian: as he kept repeating: “That’s what I do, history is written after the facts, and my photographs are showing you what’s happened”. The power of his images lies in the empathetic observation of his subject, in the human aspect that is recognizable by everyone, in the sublimated message of universal humanism.

Thank you Chris Killip.

Videos

Chris Killip (18 okt. 2016)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CaPBZIDq86Y

Skinningrove (17 mei 2017)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ENzA-vIwAgQ

Chris Killip: The Last Ships Q&A (12 sep. 2018)

‘Nobody Ever Once Asked Me Who I Was’ – Chris Killip on Photographing the ‘The Station’ in Gateshead (20 feb 2020)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ktepguMdDMU

‘I went to my father and said: Dad, I’m going to become a photographer’ Interview with Chris Killip (15 mrt. 2020)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rjfrZ7JbH7Q

Following articles already appeared about Chris Killip in the Eye of Photography

Chris Killip : The Station – L’Œil de la Photographie april 16, 2020

Now Then: Chris Killip and the Making of In Flagrante L’Œil de la Photographie May 26, 2017

Opening of Flagrante Two by Chris Killip L’Œil de la Photographie January 27, 2016

Paris: Chris Killip L’Œil de la Photographie August 31, 2012

Chris Killip –Arbeit / Work L’Œil de la Photographie March 19, 2012

Chris Killip –Seacoal L’Œil de la Photographie May 24, 2011

Sources

https://www.henricartierbresson.org/en/hcb-prize/award-winners/

johndevos.photo(ad)gmail.com