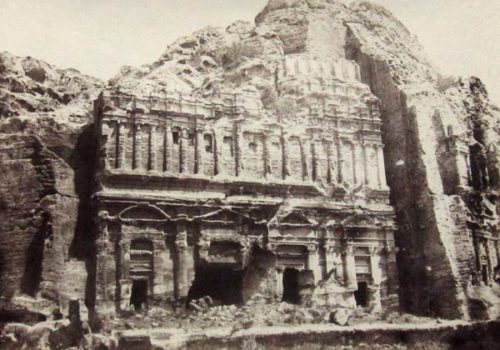

Born in Paris in 1802, Honoré d’Albert, Duke of Luynes, readily lavished his immense wealth on the arts and sciences. Late in life, his passion for archaeology and his interest for the Bible led him to plan a trip to explore a little known and then rather mysterious area of the Dead Sea. Upon his return to France, he projected to publish an account of his journey illustrated with heliogravures made from the photographs taken during the expedition. During a stay in Hyères in October 1863, the Duke met Louis Vignes (1831-1896) and entrusted him with taking the photographs. Vignes had worked with paper negative between 1859 and 1862, an experience that probably explains this choice; he was probably introduced to Charles Nègre, who was in close contact with the Duke de Luynes. Nègre had invented a process for heliogravure on steel and owned a photography studio in Nice at the time. Like him, Louis Vignes was to use albumen-coated glass for his negatives, before moving to wax paper at the end of the trip.

On February 9, 1864, the Duke of Luynes and Louis Vignes left Marseilles. They reached Beirut on February 21 and, on February 27, were headed for Jerusalem for a four-month trip. When he came back to France, de Luynes devoted his time to the preparation of the book synthesizing his expedition. On March 16, 1865, he signed a contract with Charles Nègre for the production of heliogravure plates and trial prints for Louis Vignes’s photographs by January 1, 1868. Charles Nègre started work on the commission in May. The task at hand was so considerable that he was only able to complete the gilding and etching of 18 heliographic plates between January and April 1866, and of 12 more between May and August.

Over the period, Charles Nègre also took part in the competition sponsored by the Duke of Luynes. He sent a few heliogravures made from Louis Vignes’s negatives to the Société française de photographie, which was in charge of the organization. In April 1867, the committee that assessed the participants issued a report. It was critical of the excessive complexity of Charles Nègre’s process and the fact that he had touched up the heliogravures — even though the Duke of Luynes himself had requested the alterations. According to the committee, the changes betrayed the intentions of the competition’s founder and his concern for the wider circulation of useful documents among scientists, archeologists and artists — thanks to easy-to-use, convenient methods. Alphonse Poitevin was awarded the prize; Charles Nègre defended himself rather bitterly — and unsuccessfully — in a letter to the Société française de photographie. He explained that the imperfections of the negatives had been touched up on the Duke’s request. The photographic reproduction of nature had started with light but remained incomplete and had to be finished manually, Nègre explained, revealing the nature of alterations made on the steel plates: they involved sky and water.

On December 14, 1867, the Duke of Luynes died in Rome. Under the guidance of the Count of Vogüe, his grandsons took on the responsibility of seeing the project to completion. Between 1871 and 1875, they published a memoir and an illustrated atlas in several installments, ‘Exploration trip to the Dead Sea, Petra and on the left bank of the Jordan River by His Grace The Duke of Luynes’. Charles Nègre had provided the 64 heliogravure steel plates made after Louis Vignes’s photographs intended for the atlas.

All 110 original prints on albumen-coated paper and trial prints for the heliogravures printed in black ink on paper described in this publication come from the family archive and Charles Nègre’s personal album. The numbers correspond to those of the atlas published from 1871 to 1875 by the grandsons of the Duke of Luynes. A number of prints on albumen-coated paper feature clouds drawn over neutral skies; hand-drawn by Charles Nègre, these appear mostly on reverse prints and correspond to the clouds that were reportedly featured in the heliogravures of the 1875 atlas, published in five-plate installments at 6 francs apiece. They served as markers and memory aids for Charles Nègre’s hand drawings on the heliographic steel plates. In the end, and despite the criticism issued by the jury for the Duke of Luynes’s competition, Charles Nègre succeeded in making his intentions plain with this first publication: to reproduce and to correct nature.

INFORMATION

http://www.paviotfoto.com