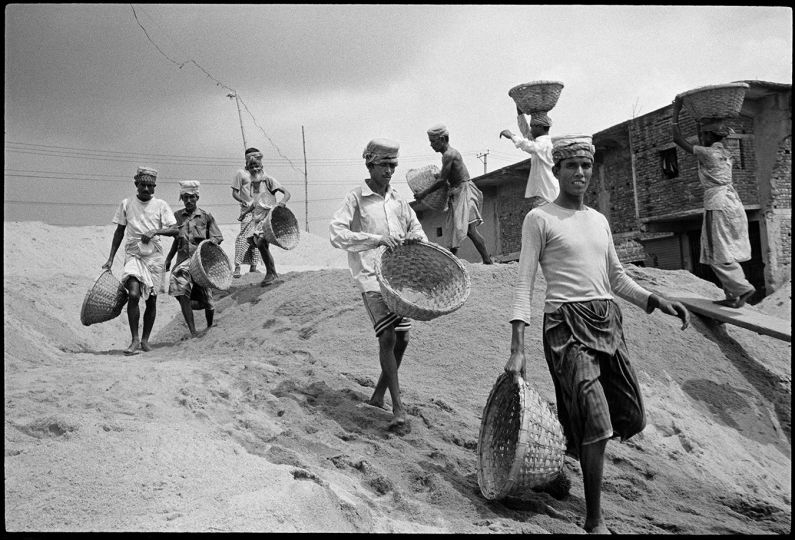

In their enormous size and grandeur, Detroit’s decayed buildings made a tremendous impression on me. Detroit Is No Dry Bones charts adaptations in the struggle for survival in Detroit’s segregated neighborhoods and the visual culture developing in them—issues usually deemed too humble to receive public attention. Thus, I seek to draw attention to those who, without any encouragement, remain in their neighborhoods, and to acknowledge their history and achievements no matter how insignificant they may seem to the rest of the nation.

Within 7.2 square miles of its core Detroit has experienced an extraordinary rebirth. This booming area, labeled “Opportunity Detroit,” will soon be completely rebuilt, with a new skyscraper, the city’s tallest, planned to be erected on the former Hudson’s Department Store site. This rebirth of what once was “a skyscraper graveyard” has deservedly received national attention. Much of the media coverage of the whole city, however, centers only on businesses, restaurants, art galleries and stores emerging within roughly one twentieth of Detroit’s surface.

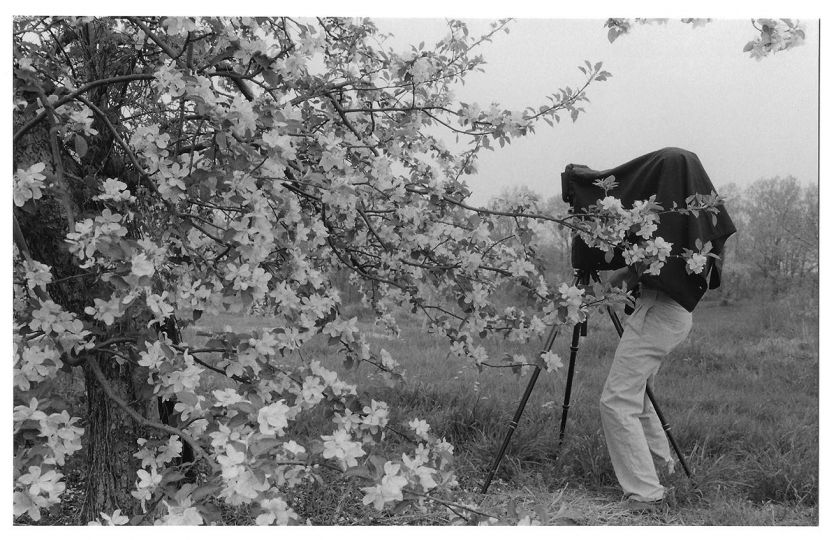

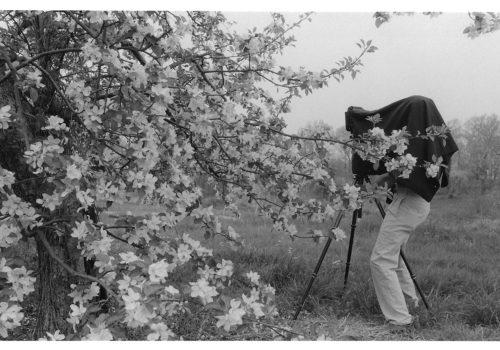

With their awesome presence, the city’s skeletons also attracted the media and the first wave of artists and entrepreneurs. Landmarks such as the Michigan Central Depot, the old Packard plant and assorted abandoned skyscrapers made Motor City unique, a world capital of ruins. I cannot deny the aesthetic attraction. But my goal has been primarily to answer the question, “what happens next,” that is, to track their evolution.

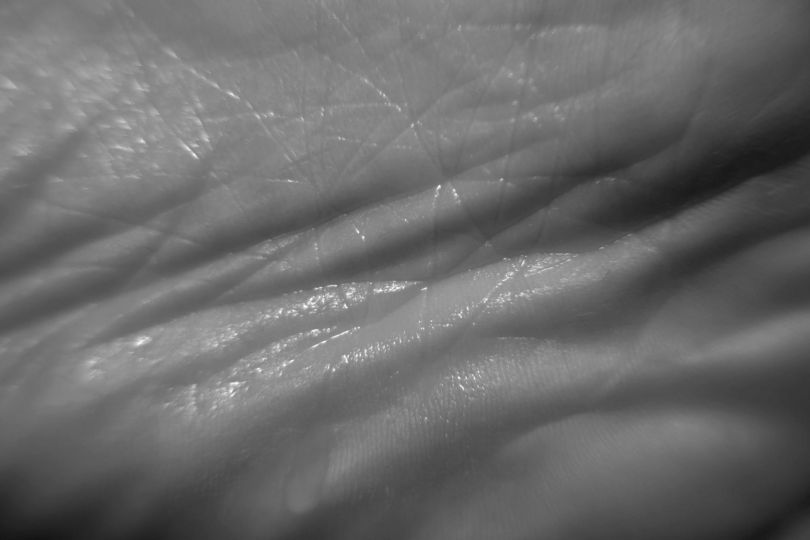

Of particular interest is the identity of these seemingly permanent ghettos as visually expressed in murals, commercial signs, and adaptations of existing buildings. There are religious murals in which Christ, the apostles, and the angels are black, and representations of African-American history that depict pyramids, civil right figures, the city’s leaders and their achievements. A reversal of the established order is evident in the size of the figures; for instance, a mural at an East Side check cashing establishment depicts a tiny Henry Ford driving one of his early cars under a huge portrait of Mayor Coleman Young gazing down from above. In “The History of Detroit” series by Sylvia Burke, buildings such as Stimson Funeral Home and the Motown Museum take precedence over the old GM headquarters and the landmark Fisher building.

The decay of buildings is a stigma. And that has led to what I consider an absurd accusation, that people who admire the grandeur of ruins are pornographers, that the photography of decay is obscene, that it is socially irresponsible insofar as it implies that city officials are to blame and that its residents are hopeless. My view is that derelict structures have a history, feed the imagination, and as in the case of the Michigan Central Depot, they have spearheaded the development of their surroundings and thus create employment. Even photographers that make short visits and neglect to show Detroit in its historical context are contributing to the understanding of the city. People interested can easily gather additional information about the images simply by doing a Google search.

Detroit’s tragedy is that, with all that we know and with all the resources available, there seems to be no way to improve the living conditions of the majority of the population. A dual city continues to develop in which a growing educated population is surrounded by 131 declining square miles where poor African Americans survive amidst decaying buildings and empty lots. Detroit’s neighborhoods continue to lose jobs and to fade away. Residents able to move out of those places do so. This situation is likely to get worse. And so we ask: Why such disconnection? Why can’t Opportunity Detroit spread to the rest of the city?

Camilo Vergara

Camilo Vergara is a Chilean writer, photographer and documentarian who lives and works in New York, USA.

Camilo Vergara, Detroit Is No Dry Bones

Published by University of Michigan Press

$55

https://www.press.umich.edu/9266258/detroit_is_no_dry_bones