The Bodleian Library and Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford is home to some of Julia Margaret Cameron’s (1815-1879) most important work, showing her aesthetic evolution as a photographer as she moves beyond straightforward portraits to more searching and allusive renderings of the human face. She took this concern a stage further with images purportedly illustrating the poetry of Tennyson but more revealing as her representations of themes that could be given a visual form.

Cameron was born in India, her father being there as an employee of the East India Company with his wife, Adeline de I’Etang, a descendant of French aristocracy. Coming to England with her family, she was in her early thirties when she threw herself into a busy social life but took note of early innovations in the art of photography through an acquaintance who sent her examples of this new and exciting invention. Beginning in 1864, she took portraits using a bulky wooden camera to produce albumen prints from large, glass-plate negatives and expanded her aesthetic awareness with considerations of framing and the availability of light and shadow. This was a far cry from traditional Victorian portraiture which was of the staged and manipulated kind motivated by a desire to document for posterity a flattering picture of a family member. Cameron, distaining any tampering with her images, was more interested in intrinsic facial qualities that could be revealed through ‘close-up’ photography– though the term was not then in common use – placing a subject’s face against a nondescript, effectively blank background that prevents the focus from being anywhere else.

The author, Nichole J. Fazio, provides insights into Cameron’s methodology and her philosophical impulse to question contemporary notions of beauty. By countenancing the presence of melancholy in her images, Cameron hints at unarticulated aspects of a person’s persona and the strangeness of being in the world. Photography takes on a poetic dimension, hence the subtitle of Fazio’s study, and the author writes of photographs as ‘a trace, a shadow, a memory – pointing toward the unreal, the non-material and perhaps an ideal’. They also, by their very nature, point toward absence and death, themes absolutely central to Tennyson’s poetry and which Cameron recognised.

What makes this book so valuable is its bringing together in print over 90 full-page reproductions of Cameron’s photographs and the additional worth that comes from Fazio’s scholarship in the form of six essays and commentaries on the photos.

With the first of three portraits of the poet and playwright Henry Taylor, Fazio observes how the way the subject’s head is carefully placed in the centre is a characteristic of the photographer. Pensiveness is emphasised by having the subject’s gaze directed downwards and to one side. The other two portraits, probably taken on the same day, are also reproduced and the second of these show Cameron capturing Taylor, or perhaps imbuing him by way of changing the light, with a look of worn-out introspection.

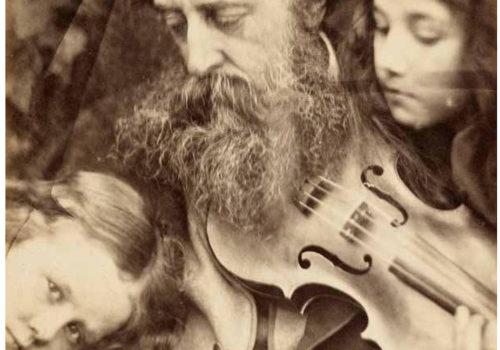

The following year, 1865, Cameron, took two portraits of the painter G.F. Watts and the second of these is one that the photographer was right to call ‘a Triumph’. In it, the painter holds a violin to his chin and looks down towards one of his children who gazes frankly at the viewer while, on the other side, her sister looks down towards the violin and hairs of her father’s beard that hang over the top of the instrument. The composition of the scene is compacted but graceful, held together with a lithe chiaroscuro that sees light directed onto the upper half of the painter’s face and the crown of his head; the falling of human hair over the strings of the violin allude to a cohesion of some kind between the arts of painting and music and, indirectly, the art of photography.

Cameron took various photographs inspired by Tennyson’s poetry and one of these shows the poet himself as an unkempt monk-like figure – Tennyson referred to it as ‘The Dirty Monk’ – rendered remarkable by a lifelike physicality that contrasts strongly with photographs by other contemporaries depicting him more formally as an august muse. A sitter, Agnes Mangles, was used to illustrate Tennyson’s poem ‘Mariana’ about unrequited love (based on the tragic character Mariana in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure) and Fazio compares the photograph with the Pre-Raphaelite painting of the same subject by John Everett Millais to deftly bring out what is distinctive about Cameron’s version. She inscribed her picture with lines from the poem – ‘My life is dreary / He cometh not, she said / |she said, I am aweary, aweary / I would that I were dead’ – testimony to the state of mind she seeks to represent: psychological isolation and consequent despair that takes the form not of heightened, intense emotion but a sheer indifference to life that in the picture seems akin to clinical depression. As an image of melancholy, it is disturbing – unlike Cameron’s portrayal of the principal character in Tennyson’s poem, ‘Maud’, where the scene borders on tweeness.

A portrait of Cameron’s niece Julia Prinsep Stephen, née Jackson (1846-1895), shows the photographer in fluent control of her medium: ‘contrasting tones concentrate the viewer’s attention on the curving lines of Julia’s decidedly contemplative pose as well as the receding shadows that create the allusion of pulsing dimensionality’, as Fazio puts it. Part of the dimensionality is the uncanny presence in it, avant le lettre, of Virginia Woolf – not altogether surprising given that Jackson, marrying a second time after her first husband, Herbert Duckworth, died suddenly, would be the mother of Woolf – but eerie because of the way the photograph captures something essential about the characterisation of Mrs Ramsey in To The Lighthouse. It is strange that Woolf’s allusive presence is completely absent from another portrait of Julia Jackson, taken in the same year, where she looks directly into the camera.

Sean Sheehan

Julia Margaret Cameron: A Poetry of Photography, by Nichole J. Fazio, is published by Bodleian Library Publishing