Homo detritus

The day after visiting an exhibition by Anselm Kiefer in Paris, I photographed the wreckage of objects exhumed from the depths of the Canal de l’Ourcq during its last scouring without thinking of the link between the works of the German artist dark and earthy, quasi-organic materials, reusing waste, and the images that I made of these decomposing objects taken out of the mud. I was spontaneously caught up in the affect of disgust for the irresponsible throw, in this eco-citizen rejection of irresponsible, non-recycled rejection. And my images wanted to testify in a way to this scandal by documenting it in an irrefutable way as only photography and film can do.

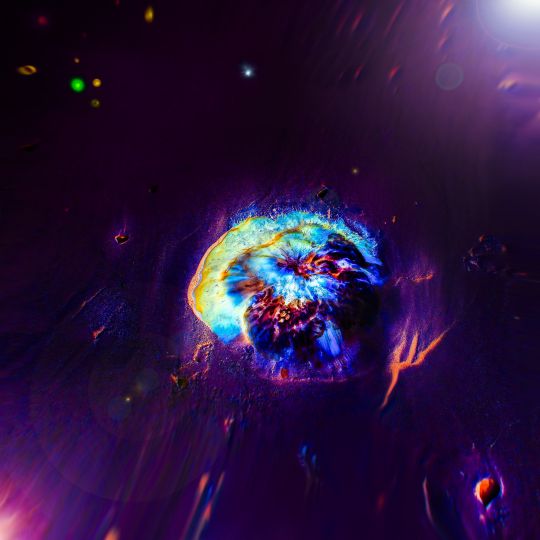

By reworking this series, I thought back to Kiefer and more generally to the rehabilitation of waste which crosses modern art (Picasso, Calder, Dubuffet, Beuys, Arman, Boltanski etc.) and which inspires the practices of many of artists today. This importance of waste in contemporary art is reminiscent of the work of the philosopher Jacques Derrida on the margin in painting. “The property of the margin, which is always the margin of [this or that], is to panic the functioning of a system, of a work, of an institution, by revealing its excesses and loopholes. In this way, it introduces into them a permanent “crisis” which we can clearly see prevents the referent from closing or totaling itself” (Christian Ruby, La prose des restes dans Raison Presente, 2021). In short, waste would not be an unworthy object, condemnable in itself, but the reminder of a state of the world based on “the double ruin of capitalist modernism and the anthropocentric modernism of humanist philosophy”. Thus, in his essay Homo detritus, Baptiste Monsaingeon campaigns for a rehabilitation of the critical virtue of waste: “By focusing on a “problem” of waste, by developing ever more complex strategies to eliminate it – etymologically, to put it on the threshold – have we not ended up forgetting, veiling the processes that generate it? By making waste an autonomous problem, detached from issues related to our way of being-in-the-world, of producing, of living, of developing our activities, we have gradually blinded ourselves and naturalized the political, economic and social choices , at the origin of the saturation of terrestrial spaces by the remains of our activities, of their proliferation making certain places of the world literally uninhabitable. This political vision of waste could be the mainspring of a new form of ecological art that encourages action more than contemplation and moral reprobation.

Bernard Chevalier