They dreamt about it, they did it. Yonola Viguerie and Philip Blenkinsop just opened a gallery in Bangkok. The first pictures exposed are by Australian photographer Max Pam and by Philip Blenkinsop. Here is an interview by Alison Stieven-Taylor of Philip Blenkinsop.”

“After more than twenty years documenting forgotten and untold stories in places that, to many, are just exotic names on the map – Laos, Nepal, Burma among them, Australian photographer Philip Blenkinsop spent most of 2010 taking stock of life, literally throwing himself into the task of sorting through an eclectic collection, his Bangkok studio filled to the point where there is no longer a corner free to create a viable working space.

Philip’s studio, which is on the 16th floor of the apartment block in which he also lives, is reminiscent of a pirate’s treasure chest, or a mad professor’s laboratory. Jars of liquid in which strange creatures are immersed vie for position on shelves that are cluttered with curios that Philip has collected on his travels throughout Asia.

Virtually unknown in Australia outside the inner-circle of the photography world, Philip has lived in Bangkok since 1989 where he landed after throwing in his job as a newspaper photographer in Sydney for the uncertain life of a freelance photojournalist.

This wiry, intelligent man who wriggles with nervous energy throughout our Skype interview is more at home trekking through the jungle with guerillas or in the frenzied chaos that is Asia than he is in Australia where life is just too staid for such an inquiring mind.

Through the lens of his camera he’s recorded stories that would not have seen the light of day had it not been for Philip’s resolve to lend a voice to those rendered silent by circumstance. His photo essay on the Hmong people, Veterans of a Secret War, is a case in point. To capture this story Philip trekked high into the mountains of Northern Laos in 2003 and came away with startling images of the horrific suffering of the Hmong at the hands of the Lao Army. Persecuted for their allegiance to the US in the 1960s and 1970s, these people have been abandoned by the world. The images are deeply disturbing, but Philip is unapologetic. He says of photojournalists, “Our responsibility must always lie with the people we focus on, and with the accurate depiction of their plight, regardless of how unpalatable this might be for magazine readers”.

I first met Philip in Fremantle, his hometown, in March last year at the Foto Freo festival, his exhibition on East Timor part of the programme. In the evening light with a scarf wrapped around his neck, and a gold ring dangling from his ear he exuded the aura of a rock star, those aware of his work eager to seek an audience with one of this country’s most ground-breaking photographers. But despite the rock star air there is nothing egocentric about Philip or the images he takes. Quite the contrary. Philip is deeply committed to his work and his subjects, the potential for his own celebrity forgotten in the pursuit of a story. He makes a living out of exhibitions and selling his photos to international magazines and news services, but it’s hardly lucrative and there is little financial security.

When we reconnect in December via Skype Philip is in his study in the Bangkok high-rise he calls home. A summer storm sweeps through interrupting our chat momentarily as Philip gets up to close the window averting a potential drenching.

He tells me he’s had a frustrating day dealing with the bureaucracy as he tries to get his new workspace into shape. He’s chosen a street frontage in the Chinatown section of Bangkok. He moots the idea the place may be haunted, it has been vacant for decades, “there’s a good reason for that, but we are yet to find out” he says his eyes sparkling with both intrigue and alarm at the thought of what he may uncover during the renovation process. Today he is dealing with water – getting it connected for the darkroom and also trying to stop the leaks in the roof. I remind him that he’s had to deal with leaking roofs in the past. There was an exhibition space in Lianzhou, China whose holey roof drove him to distraction while he was trying to set up his show in 2007. He smiles wryly at the memory, but says this time the water leaks are much greater. “We are going to have to replace the roof not just patch it.” He is resigned that progress may not be as fast as he’d hoped.

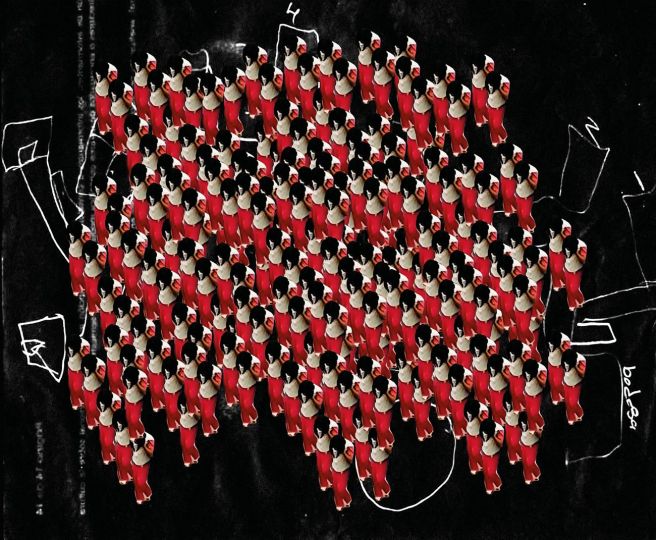

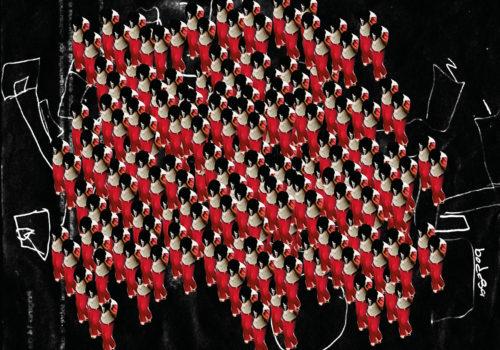

The motivation for the new space is partly driven by the fact he no longer has room in his existing studio, “but I also wanted a street frontage so I can invite people in to see the work”. He intends to work with painters, sculptors, “artists of different backgrounds and persuasions and to open the space to residencies. I am interested in exploring the idea of incorporating other visual art disciplines with my photographs, of moving away from the photographer-writer-storytelling narrative to find new ways to present the work”.

He admits this is a “very different headspace for me after years of going from one story to the next. Not that I’m terribly prolific,” he states although his list of achievements including more than 30 exhibitions around the globe tend to contradict this assertion. Philip’s “dip for the year” photographically speaking was a trip in 2010 to Bangladesh where he was on assignment for the Amsterdam-based photo agency Noor as part of a collaborative environmental climate project, Solutions. The year prior images from stage one of the project, Consequences, were presented at the climate summit in Copenhagen in association with Greenpeace.

In Bangladesh, “a wonderfully chaotic place where the density of the population is phenomenal…something I adore”, Philip focused on photographing “anything that moved under human power including bicycles and rickshaws…It’s nothing new, the idea of bicycles, but I think in terms of environmental solutions it is something that is perhaps overlooked”.

Philip’s segue into environmental photography began in 2008 when he shot the Yellow River in China one of the most polluted waterways in the world. Of his focus on the environment he comments, “I reached a point where it was pretty obvious that (the environment) was the story. It wasn’t like I was asking myself what do I do? Or saying I have to do this. It was more that I really wanted to do something to help and I thought that it is my responsibility and others with the same possibilities as I have, to work on these stories and achieve an outcome. I know it’s a very difficult thing to photograph, and you are often less welcome than in a guerilla zone where people are very happy to see you, but it’s a story that needs to be told”.

We toss around the idea that print editorial is dead, a recurrent theme I’ve discussed with many photojournalists I’ve interviewed over the past few years. Philip is of the opinion that finding an outlet for photographic essays is “one of the big hurdles facing the industry now. Where do you publish and how? I’m not altogether sure what the answers are yet. It is all about content and we are all content providers, but that doesn’t sit comfortably with me”.

I ask him if the Australian media publishes his work. He tells of a recent encounter with an Australian journalism magazine where the editor refused to run an interview with Philip because the pictures weren’t in the “best interest of the magazine’s readers”. The incident confirms for Philip the narrow view taken by Australia’s news media. “That’s why I never even think to call Australia with a story because I don’t need that disappointment and frustration”.

Shifting the conversation to the Internet Philip says he is not particularly drawn to the online world. “I really don’t think we have to be slaves to this digital technology. Just because we can have an iPad or because we are capable of shooting digital video, doesn’t mean we should. I think the industry has gone a little bit moronic. It seems to be all about the delivery, not even the style of delivery, but the tools that we deliver the story with or by. It’s become so much about the delivery that I’m becoming less and less interested”.

He steers the conversation back to the new space he is working on. “I am hoping that this place will give me the chance to work on a larger scale and explore those memories and the people that I’ve met and the faces I’ve collected over the years. It will give me a chance to go back and try to make a bit more sense of them and to develop them in different ways. I want to create an object that has a real weight to it, that isn’t just zeros and ones, a virtual image on a screen that actually doesn’t exist in reality. I very much love the idea that these things do exist. I think the big thing for me is allowing other people to appropriate my memory of an event and I think that’s very, very important to their understanding and their interpretation of the picture or their appreciation of the people in an image.”

The new space, “let’s not call it a gallery I really cringe when I hear that word,” has been named the Lulik Haunt. He explains a Lulik “is a talisman that the guerillas in East Timor carry with them usually around their neck. It can be anything from a lock of a man’s wife’s hair to a handful of dirt from their village. It is really anything that is perceived to have magical powers”. Philip’s not sure if this new venture is something that is “going to allow me to survive, but if you get too hung up on that then you do things for the wrong reason. If you are thinking about the money and what’s the best way of making money you are not necessarily thinking about what is the best thing for your trade or your craft or for the people you photograph, your subjects. If I’m not happy doing my work then I can be a real miserable son of a bitch,” he laughs.

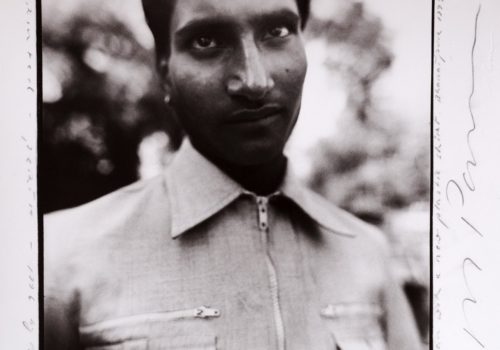

His archives are extensive, but his starting point will be “the people who are special and the times that I have had that hold significant meaning for me. There will definitely be photos, for instance, of Taur Matan Ruak now the Brigadier General of the East Timorese defense force with whom I spent about three and a half weeks in the mountains in 1998 when they were still fighting for independence”. There will also be photos Hmong Commander Moua Toua Ther, the injustice of the Hmong peoples’ plight something Philip still wrestles with.

The vision Philip has for the Lulik Haunt is to create work that is “shamelessly personal, in some ways autobiographical. I want to develop it at this level and put the work together in such a way that the total aesthetic will lift everything to a place where the work will be more accessible to people. That’s the goal”.

The wonderfully chaotic world of Philip Blenkinsop by Alison Stieven-Taylor © 2011

2SNAKESTUDIO

Soi Nana, Maitri Chit Rd (near Hualumpong Train station) |

Bangkok

08-6012-1272 | By appointment only | MRT Hualumpong