Aurora Király’s Viewfinder (2014-2016) was one of the revelations at Paris Photo this year: Presented by Anca Poterașu Gallery (Bucharest) in the Voices section of the fair, alongside Viewfinder Clash (2020-2021) and Viewfinder Mock-Ups (2016-2019), the series entered several private collections, while two pieces are in the process of being acquired by the MoMA. In a conversation with Sonia Voss, curator of one of the three Voices stands, Király discusses the Viewfinder series and puts it into the context of her oeuvre.

Born in 1970, Aurora Király is a Romanian artist working at the cross-section of various media, primarily photography. She teaches in the Department of Photography and Dynamic Image at the National University of Arts in Bucharest. She is also a curator and initiator of cultural projects. Her series Melancholia (1997-1999)—a fragmented black-and-white photo-journal in which Király played the dual role of voyeur and subject of observation, shown at Paris Photo in 2022—served as source material for her more recent photographic objects.

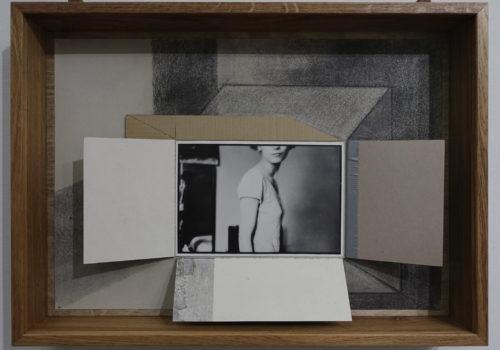

Sonia Voss : Your work has recently revolved around your own artistic archive, which you have been recontextualizing and mingling with a reflection on the photographic medium itself. In Paris Photo this year, you showed several pieces from your Viewfinder series: three-dimensional objects conceived around prints chosen from among the photographs you produced in the early 1990s—mostly self-portraits evoking very personal moments of doubt or introspection. Scraps of cardboard are transformed into artefacts that unfold in space and reframe the vintage prints. Viewfinder places us at the cross-section between fragile intimacy and a conceptual exploration of possible material extensions of the medium.

Aurora Király: Photography is central to my artistic practice. Often, even when working in other media such as drawing, textiles or installation, my works inevitably refer to the photographic medium—whether through technical aspects, the photographic process itself, or the theoretical and conceptual perspectives it offers.

I began the Viewfinder series, presented at Paris Photo this year, almost ten years ago. Most of the works in this series are medium-sized (50 x 70 cm) and exude a certain intimacy, including many self-portraits as well as scenes from my workspace or details of objects from my own photographic archive. The folds of cardboard built around the image, the covering of certain parts of the work and the charcoal lines tracing axes, all evoke the concept of framing—the decision that the photographer makes when pressing the button or the shutter release. Even though digital environments now allow us to manipulate images on a computer ex post facto, the initial act of framing in photography requires us to visualize a preview of the image we want to capture. This is the moment I’m dealing with in this series.

Recently, when I started to add new large-format pieces (125 x 180 cm) to the Viewfinder series, I discovered the different possibilities this size offers, thanks to its new rapport with the human figure. The cardboard panels resemble windows, and photography takes on an immersive role in the ensemble. My participation at Paris Photo in the ‘Four Walls’ exhibition that you curated as part of the Voices section allowed me to see these works with a fresh eye and understand the choice of photographs for each piece of this series—how important it is for them to have an intriguing and magnetic quality, even where they depict everyday situations.

Reactivating an archive and translating it through new photographic materialities was also an important motivation for the new work you began in Mulhouse in early 2024, during an AFAR residency there (the AFAR-Artists for Artists Residency network is an EU co-funded project and residency program aiming to improve the mobility of contemporary visual artists and curators in Romania, Germany, Croatia, and Austria), based on the city’s tradition of textile production, mainly carried out by women. In that case, you conducted research into numerous sources—written, textile, and photographic—trying to get familiar with a history to which you initially had no direct connections. What was your motivation for approaching this particular segment of the region’s history? The involvement of women workers in the textile industry is not specific to the Mulhouse region and can be observed in many parts of the world. In the context of East Germany, I cannot help thinking of the photographs of Evelyn Richter, who documented women textile workers in the GDR. Does your work on this subject address Communist or post-Communist Romania’s socio-political reality, as well, or were you more interested in non-historical elements, such as gesture and posture, the body’s relationship with the machine, or even textile patterns and materials?

Concerning the work I created during my AFAR residency at Kunsthalle Mulhouse, it shifts into an entirely different register. From the outset, my intention was to ground the work in the history of the region, particularly its textile manufacturing and industrial heritage.

I connected with this topic during my residency in France, and discovered a theme I want to explore further in different geographical spaces. Of course, it has particular resonance in Romania, where many textile factories were shut down in the 1990s and 2000s. There is an interdisciplinary approach to looking at the textile industry as a complex sector reflecting local economic trends as well as global production systems, and I would very much like to continue my exploration of this topic in the future.

During the AFAR residency, some of my recurrent themes—the female body, its various stages of life, and the evolving status of women in society—took on new depth and context. Photography was the primary tool through which I examined what I discovered in my research. I worked with photographs that I found in antique shops, and which offered glimpses of women from the region of differing age and social status, as well as archival photographs—these served as key sources for the projects I developed there. As I delved into these vernacular images, I began to notice recurring patterns in the representation of women’s bodies.

Your mention of Evelyn Richter’s photographs of GDR textile workers is timely. Reflecting on these images now, in light of my recent research, I see how much they convey—resilience, solidarity, focus, and more. Similarly, the photographs of women workers in the textile mills that I discovered in the Mulhouse City Archives drew my attention to the female body at work. The posture of these women, shaped by long hours of repetitive work, and their status in the early days of industrialization became key themes in my project.

In the first pieces you created based on your residency in Mulhouse, the postures and gestures of the workers are reduced to a silhouette, which lends added emphasis to their shape. You also address the repetition of gestures, as a kind of analogue to the repetition of patterns in the fabrics. I see this as a metaphor of the artist, who, in her search for new forms, keeps repeating the same gestures over and over. In addition, the mechanical aspect of the loom and the reproducibility of patterns it facilitates recall the first principles of photography.

Seeing these recent works, I thought of your series Soft Drawings—which, in contrast to what their title implies, are light boxes (2021)—as well as your series of photograms Subconscious Narratives (2021), and likewise Drifting… (2016). In all these works, you draw and arrange the contours of figures and objects. In Drifting…, you also construct a narrative based on the life of migrants, whose silhouettes you present as Balinese puppets with shadows cast on the wall, bringing us back to a kind of proto-photography. With the pieces from Mulhouse, I feel you likewise want to boil down the archival images you are working with to elementary forms that bring us back to the origins of something—childhood memories, common experiences of perception…

In analyzing the archival photographs, I began by synthesizing the silhouettes of these women, who were part of a social group whose contributions to the city’s economy have long been overlooked. In order to emphasize their role and make their contribution visible, I transformed the silhouettes into modular shapes, which I then used to create rhythm and ultimately to multiply them in creating a background.

This process reflects a parallel between the reproducibility of motifs in fabric—whether woven or printed—and the multiplication of images through analog darkroom printing. This similarity is what drew me to the textile medium in recent years. I further explore this relationship by comparing pieces of textile to photographic negatives, specifically through the use of transparencies in the fabric structure. I create these transparencies by carefully unraveling threads, following the lines of a preliminary drawing. When light is projected onto the piece, the transparencies come to life, revealing the image much like a photographic negative.

My works are often interconnected, starting with a theme that I explore across various mediums. This approach allows me to process a subject through different lenses—such as photography, objects, drawing, or textiles. The theme and the medium work reciprocally on each other, and I find it essential to test the full range of possibilities. Each shift of medium brings new specificities, and this fluidity sometimes challenges me to re-define the work, precisely because the media are often intertwined: Is it an object that uses photography, a sculptural drawing, or mixed media?

The Soft Drawings series embodies this ambiguity. The title suggests drawings, but the works are photographs presented in light boxes. This play on perception explores the potential of photography and darkroom techniques, such as photograms—where light is cast from above to expose a photosensitive surface—or the process of photographing various elements lying on a light box, where the light comes from below. In both cases, the medium itself is part of the conceptual exploration.

The Drifting… series follows a similar process, but here, the silhouettes are drawn from press images depicting war scenes or other dramatic situations. I began the project in 2016, during the migrant crisis when waves of refugees were arriving on the southern coasts of Europe. I selected figures from documentary photographs available online, isolating or erasing some of the most striking characters. My focus was on visually intense, dramatic moments. These cut-out figures were then mounted onto cardboard and fixed to sticks. When projected, they cast shadows onto a white curtain.

At first, the installation appears serene, almost mesmerizing—similar to the shadow play in Balinese theater you mentioned. But as the viewer draws closer or looks more intently, they realize that these figures are in critical, precarious situations. Only then does the connection between the photographs and the shadows behind the curtain emerge.

The work also evokes early efforts to capture photographic images, while simultaneously addressing themes of perception, illusion, and the relationship between photography and its reflection of reality—especially in the context of digital photography and AI.

Aurora Király

Sonia Voss

Aurora Király – Viewfinder

Presented during Paris Photo by Anca Poterașu Gallery

Strada Popa Soare 26, București 023983,

Romania

www.ancapoterasu.com