Bruce Davidson, one of the most influential photographers of the last half-century, has spent his life observing and capturing lives on the margins. He approaches his subjects – whether subway commuters, circus dwarves or coal miners – with curiosity, directness and empathy.

Though best known for black-and-white photography, he has been shooting in color for more than 50 years, as his recently released book, In Color, attests. As he said in a short video released by his book’s publisher Steidl, “Black and white is my wife. Color is my children.”

Davidson’s work, from early black-and-white street photography to color editorial work, is currently on view at Jackson Fine Art through August 1. The show is not encyclopedic, nor was it meant to be, but it does succeed in conveying his versatility and in showing his less familiar side.

As you enter the gallery, a photograph of closed doors taken in the subway of New York, Subway, New York, (doors) 1980, confronts you. The subway’s metallic doors bisect the image, leaving parts of the human cargo visible on each side. Humans appeared alienated from this dark environment, as rendered in the hostile look in Woman, Subway, New York, 1980.

Davidson defines this work as pivotal for his exploration of color photography. He began in black and white but soon realized that using color could provide a deeper meaning. He saw tones that reminded him of “an iridescence like that I had seen in photographs of deep-sea fish.”

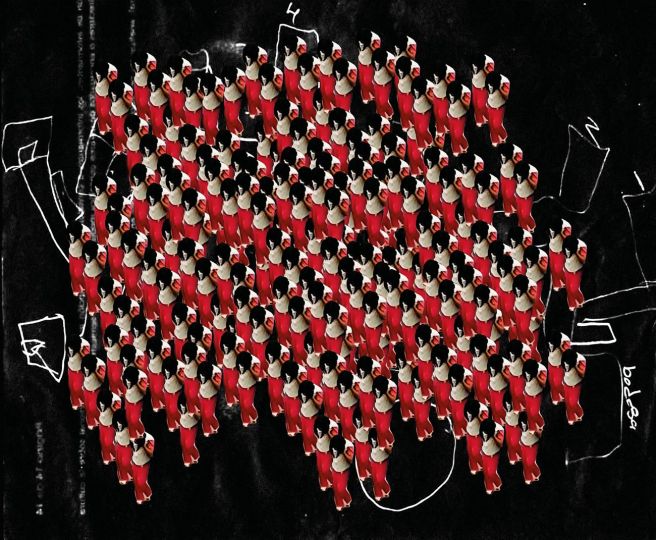

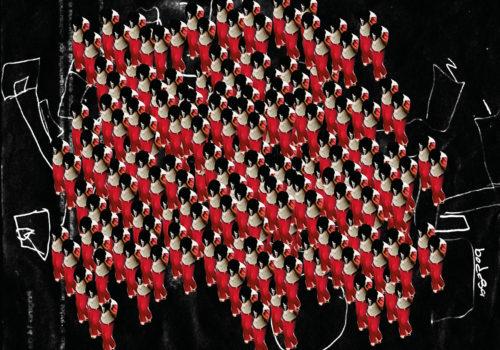

Photographs taken during Diana Ross’ tour, entitled The Supremes, in 1965 are more interesting for their ability to provide us with intimate behind-the-scene portraits than their use of color.

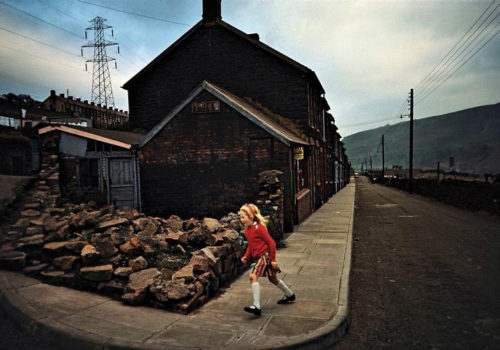

One section of the gallery is devoted, justifiably, to his 1965 series on the coal miners of South Wales. This work is stunning in its ability to translate the horrible living conditions of the miners – at work, at home, with family – into something both beautiful and awful. Davidson, who considers it to be one of his best bodies of work, started in black and white. “I shifted to color because it was the best way to show the contrast of blackened powder on the skin, the only way I could render the acid chartreuse gas coming out of the factories against the dull skies,” he explained.

This is particularly true for the unsettling Wales (group of miners), 1965, in which miners stare straight at you. Their faces and stern expressions are a chilling reflection of their hardships, and not soon forgotten.

The exhibit also showcases his 1959 series, The Brooklyn Gang, the work that first earned Davidson notice. As much as his Wales’ series reminds us of work by Cartier-Bresson in the way they are composed, the 1959’s Brooklyn Gang has the tension and structure of Eugene Smith. Davidson was 25 when he decided to document the life of the Jokers, after a social worker facilitated his introduction to them. He immersed himself in their world, blurring sometimes his identity with theirs.

“In time, they allowed me to witness their fear, depression and anger. I soon realized that I, too, was feeling their pain, in staying close to them, I uncovered my own feelings of failure, frustration and rage,” he wrote.

His close relationships to his subjects have caused controversy, notably in 1970 after another series on inner-city ghetto life, East 100th Street was published. The rawness of the photos and the unswerving intimacy of his interiors shots shocked critics, but this work is now considered a classic work of social advocacy.

The exhibition ably presents the range of his style and subject matter leaving the viewer wanting to see more. So it is with the artist, who has often said that his favorite picture is “the one that comes next.”

EXHIBITION

In Color / The Brooklyn Gang

Bruce Davidson

From May 15th to August 1st, 2015

Jackson Fine Art

3115 East Shadowlawn Ave

GA 30305 Atlanta

United States

http://www.jacksonfineart.com