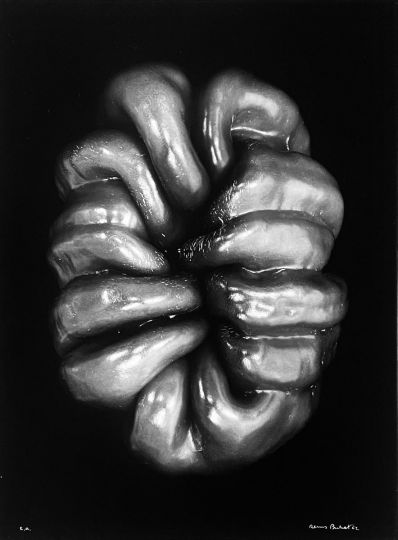

There’s something in Josef Koudelka that’s a mixture of humanity and mysticism, of strangeness and familiarity that gives each of his images, particularly the ones of gypsies, a memorial dimension that stays with you, like Robert Frank’s Americans. Koudelka’s prisoner walking toward his execution, invading the foreground with an air of resignation, reflects the growing individualism of contemporary society. In the background, the unmoving crowd balances the obliquity of the man condemned to death.

There is in Koudelka’s photographs this total immersion, not intrusive because it’s shared, this nomadism that defines him when, returning from Paris or London, he sleeps under a table or a sofa at David Hurn’s house or in the Magnum offices. When he shamelessly captures a group of traveling musicians, they seem to play for him, showing their asymmetric smiles accentuated by the proximity of the camera. The vigil for the dead expresses its symbolism by a composition that makes Koudelka a member of Cartier-Bresson family.

Koudelka’s family portrait, where the lines of the tapestry bind each generation, confirms his aesthetic and documentary richness. Beyond his sense of composition is an anthropological approach inspired by studio photography—where the traditional outfits, impressive poses and ambient backgrounds allow for a cognitive apprehension of the context—and the first explorers, detailing in pictures an unknown hierarchy. The social and familial interaction is inherent, sometimes even in animal relationships; we all remember that image of a white horse with the curved spine who seems to listen carefully to the man kneeling at his side.

The exhibition at Arles brings together a selection of photographs by Koudelka and the publisher Robert Delpire.