Anne Wilkes Tucker was named “America’s Best Curator,” by Time Magazine a decade ago. Tucker, the Gus and Lyndall Wortham Curator of Photography at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, may now be one of the foremost Curator’s of Photography in the world. Thanks to her curatorial wisdom, curiosity and scholarly research, she has built the Museum of Fine Arts Houston Photography Collection from virtually no photographs when she started in 1976, to one of the finest collections in the world. With over 26,000 images, including masters Andre Kertesz, Josef Sudek, Edward Steichen, Robert Frank and Diane Arbus, Tucker has also had the foresight to collect many lesser known international and emerging artists on the cusp of success whose careers have since taken off in the public eye.

This week, the first large-scale U.S. exhibition of Helmut Newton’s photographs will premiere at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston on July 3rd. The exhibition features the entire contents from Helmut Newton´s first three groundbreaking books: White Women (1976), Sleepless Nights (1978), and Big Nudes (1981).

I spoke with Ms. Tucker just before she began hanging the upcoming Newton show:

Elizabeth Avedon: How did the Helmut Newton show originate?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: The Museum has a very close working relationship with Manfred Heiting. We purchased his collection of photographs in 2002 and have continued to work with him since then. Heiting and Helmut Newton were close friends. In discussion with Helmut’s wife, June Newton, June came up with the idea of showing all the photographs in Newton’s first three books, which were really the beginning of his fame in the photo world. He had certainly been a fashion photographer before that, but White Women, Sleepless Nights and Big Nudes really cemented his influence and status, so that’s what we are showing. Manfred had organized a big show of Newton’s work in Berlin before that traveled all over Europe, but Newton had never really had a large show of his work in the U.S. ICP had had a smaller show, but this will be the first major exhibition of his work. Of the two hundred and six photographs in this show, some of them are very large at 6.5’ x 4.75’ feet. It will be a very full exhibition.

EA: Who designed the show?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: Manfred is the guest curator and is a designer himself. It’s his show. He has designed everything, the book, the exhibition and all the press materials.

We’ve done a publication with essays for this show (texts by June Newton, Peter C. Marzio, Anne Wilkes Tucker, Pierre Bergé, Anna Wintour, Josephine Hart, Karl Lagerfeld, and Manfred Heiting, published by MFAH). And Friday, July 1, there will be a conversation with Manfred Heiting, as a friend collaborator of Helmut all these years, and I, about the exhibition.

EA: What Newton images stand out for you in this exhibition?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: One of the things I thought was interesting that I enjoyed learning when I did the research for my essay in the show, was how Newton, not always, but frequently took the setting and models from a fashion shoot, and then after he’d done the work for the magazine, either disrobed the model or altered the dress, like slit it all the way up to the hip or something, how the boundary between those two lines kept shifting for him. Less in Big Nudes, as Big Nudes was a specific project that he did not for the fashion magazines, but something he conceived and carried out. But for Sleepless Nights and White Women they would sometimes start as fashion and he would take photographs for himself out of the same material, and how he redirected one in one direction, and one in the other, but knowing it’s market.

EA: What was your professional history before the Museum of Fine Arts Houston?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: I majored in art history in college. I got interested in photography, so I was the photographer for the yearbook and the newspaper in college, and then got a second undergraduate degree as a photographer at the Rochester Institute of Technology. I didn’t think I was a very good photographer when I got around other photographers, so I moved across town where Nathan Lyons was beginning what became the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester. I got an MFA in photo history studying with Nathan and Beaumont Newhall at the George Eastman House (Newhall founded the Photography Department at the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1935; and was Curator and Director of the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, Rochester), and then I had an internship at the Modern (MoMA, the Museum of Modern Art) working with John Szarkowski and Peter Bunnell, so I was really lucky. And in the summers I was in graduate school, I worked in the Gernsheim Collection at the University of Texas. So in a very short period of time, I had access to the Collections at the Eastman House, at the Museum of Modern Art, and at the Gernsheim Collection. I really had an extraordinary exposure to the history of photography in those three Collections. This would never happen now, but they would just let me after hours go through the boxes and look. “No Permiso” now, but it was in the Seventies and all three institutions just let me work and go through the boxes and look. I was working, but I was learning a lot being exposed to Szarkowski, Newhall and Lyons.

EA: How did you arrive in Houston?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: I was married to someone at that time who got a job in Houston and it had been our agreement it would be some place where I might get a job. As the Gods would have it, my mother lived there and Beaumont Newhall was lecturing there the night she found out we were moving to Houston. She went up to Beaumont after the lecture and told him I was moving there. He turned to the then Director, Bill Agee, and said, “You are looking for a photography curator and one of my students is moving here.” I started two days a week and then worked my way up.

EA: What did the MFAH Photography Department consist of when you started there?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: Well there was a funny collection here. They had a group of Edward Curtis, and a group of Geoff Winningham, and Lewis Baltz 1974 series The New Industrial Parks, which is a pretty diverse group, but that’s about it. They had a few this and that’s, one Aaron Siskind and one Arthur Siegel, not much more than that. They had some Roy Decarava, so it was just building from that.

At first we only collected American 20th century, just as a way to begin. That was in 1976. Then by 1983, we were also collecting European 20th century, and now it’s from 1840 to the present, all seven continents. American and European are still our strengths, although we’re strong in Latin American as well. The Collection is now over 26,000 photographs.

EA: In creating the Museum of Fine Arts Houston Photography Collection, were you influenced by your work with Newhall, who built the early MoMA Photography Collection?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: You just can’t separate the influence of Beaumont, Nathan and John. I learned such different approaches from all three. Beaumont was the historian. There’s so much more written about photography now than there was then. Back then it was a matter of spending hours and hours and hours going through original documents just to track down people. I learned from Beaumont how to do that and to organize it coherently and think about it and place it in context.

John, who was certainly one of the great writers, was not a researcher, he was not an historian the way Beaumont was, but John was such a disciplined thinker and he had such clear ideas about what was and what was not a photographer, or good photography.

Nathan was much more willing to look at a broad range of expressions in photography and embrace them. The kinds of shows that Nathan did were much more varied and much more universal than the kind of photographers that John embraced, so in a way working for the three of them so early forced me to find my own path.

It wasn’t a matter of just imitating one of them, because their ideas were so different about what photography was and wasn’t about. It was very intense, but rich experience.

EA: Can you explain your title as the Gus and Lyndall Wortham Curator of Photography?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: In 1984, Gus and Lyndall Wortham gave an endowed chair to the Museum. It’s not a photography specific chair, when I leave it might go to another curator. When it came in, the Director gave it to me. We have other curators who have endowed chairs now, but I had just gotten a Guggenheim then, so I guess he was feeling I deserved it.

EA: How did your Robert Frank Exhibition in 1986 come about?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: In 1983-84 we were able to make some rather extraordinary acquisitions. We purchased Bill Larson’s Collection of Maholy-Nagy, and we purchased a private Collection of work around the Bauhaus, and we purchased the Collection of John Heartfield AIZ Magazines, and we purchased the complete set of Robert Frank’s The Americans. Part of the agreement with Robert Frank was in purchasing The Americans we’d be able to do a show. Robert asked I do the show with Philip Brookman, which I was happy to do, that began a friendship that continues today. He’s the Chief Curator at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. now. That show, and the film we did on Robert too, all came out of being able to purchase the set of The Americans.

EA: You’ve had several ground breaking exhibitions. Would you talk about some of these?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: I’ve always been most interested in what we don’t know, than what we do. I wasn’t ever interested in doing shows that had already been done. Also, in the early ‘80’s we began to collect European photography and a dealer, Rudolf Kicken, showed me some Czech Avant-Garde photographs from the twenties and thirties. I didn’t know anything about them, but I thought they were wonderful. We acquired some, and then I went to Czechoslovakia and went to the museums. I realized how incredibly rich that period was and came back and talked to the Director about not just doing a show of photography, but the eventual show was photography, paintings and drawings, and film and sculpture. It was a whole survey on the Czech Avant-Garde of that period.

We worked on that show from 1984-89. It opened in 1989 and that’s when the Wall fell. Václav Havel was in New York the same time our show was opening so we looked so clever. The world went from no interest in Czechoslovakia to this.

Buzz Hartshorn, now the Director of ICP, was also one of the curator’s on the show because they were going to take the show at ICP. When the show came to New York, the films went to the Film Anthology, the paintings, sculptures and drawings went to the Brooklyn Museum, and ICP had the photographic section. The New York Times treated that as three shows, so on the front of the Arts and Leisure section there were three separate reviews all at one time. Of course I went out and bought a huge stack of New York Times. I’m riding up in the elevator at a friend’s apartment and this guy takes one look at me and he says, “And on what page is your name?”

A similar kind of instance led to doing The History of Japanese Photography, just looking at where there was strong work and nothing published. The same idea had led to our doing the Louis Faurer Retrospective, although that was Robert Frank’s idea because Louis was a friend and there was nothing out there on him, he had no books. Robert felt it needed to be done and I perfectly agreed with him and I was happy to do it for that reason.

And then the same motivation is behind the current show we’re working on, The History of War Photography. It will be just a little project! The prints in the show go from 1848 to the present and are taken on six continents. That show opens in November 2012, but we’re working madly on the catalog now.

EA: And where does The Great Wall of China: Photographs by Chen Changfen exhibition fit in?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: The other type of exhibitions I’ve done, are one-person shows that are kind of mid-career or project oriented. Those came about when I saw a body of work I thought was particularly strong by a photographer, rather than being some retrospective. Within that realm would be Joel Sternfeld’s American Prospects exhibition and Catherine Wagner’s American Classroom exhibition.

I knew someone from Houston living in China who came back to visit family and brought those photographs by. Mr. Chen had photographed The Great Wall over a 30-year-period. I just thought they were beautiful. It was an interesting exhibition because it wasn’t critically well received, at least not in the broader photographic press, locally it was very appreciated, but it is an exhibition which people are still coming up to me and talking to me about how much they enjoyed it. The pictures were very beautiful, and as we know, beauty is not in fashion. It wasn’t that it was politically incorrect: it just wasn’t au courant.

EA: You’ve written essays for and have been published in many books. What do you see is the importance of publishing?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: Someone said it’s over 40 books and our Archive person said I’ve done over 270 shows, but that includes smaller shows.

There are two things I learned working at those museums, MoMA, Eastman House and the Gernsheim. One was, often people would do shows and not only would they not publish anything, but they wouldn’t buy anything out of the exhibition. They put all this time and energy into doing the show and then ended up with no works in their Collection. One of my resolutions was that we wouldn’t do that; that whenever possible we would publish a catalog and we would raise the money to buy works out of the show that would remain after the show was gone. The shows are wonderful, but they are relatively short lived and if you don’t make an effort to preserve the research that you did, then it just slips away. It always seemed to me if you are going to put that much time and energy into something, that you then just have to follow through with a publication.

EA: I just saw Radius Book’s is coming out with an essay by you accompanying Gay Block’s photographs. (About Love: Photographs and Films 1973-2011, Radius Books, 2011)

Anne Wilkes Tucker: Gay’s been a friend since I first moved to Houston in 1975. When Radius decided to do her book, they came to me and asked me if I would do the text. I said, “Let’s just have Gay and I talking because we’ve known each other for so long.” It’s a wonderful survey of Gay’s forty-year career as a portrait photographer. I think we were all pleased with the way they’ve done a wonderful job of editing the book and making the selection. As well as I know Gay’s work, I was just delighted to see in going through her files, they had found some pictures I’d never seen before.

Some of them, where there’s not an organized exhibition attached to them, are where somebody’s come to me. I have a couple of essays coming out, like The Jewish Museum in New York is doing a big exhibition that opens in November of their Photo League Collection, The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951. They came to me to contribute because I did all the initial research on the Photo League in the 1970’s, so it’s an area I’m known to have some expertise in. And also because of my research on the Photo League I have an essay right now in a catalog published by the Museo Reina Sofía in Spain on the Worker-Photography Movement.” (The Worker-Photography Movement, 1926-1938, Museo Reina Sofía, 2011)

When you are known to have done some scholarly work in a particular area, then it’s not uncommon that someone will invite you to participate in something.

EA: Can you tell me a little about the history of FotoFest, Houston’s International Biennial of Photography and Photo-related Art?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: FotoFest is the baby of its founders, Wendy Watriss and Fred Baldwin. Whatever any of us might contribute is just a fragment of the time, energy, concentration, and passion that goes into that project that Wendy and Fred put in. I’ve been on the Board, I’ve been on the Exhibitions Committee, and I’ve been a Reviewer since the beginning, and I’m happy to participate, but it is Fred and Wendy’s baby.

EA: People who have participated over the years have all said you are such a dedicated Reviewer. You are very generous with your time, keeping a list by you and letting people sign up to see you.

Anne Wilkes Tucker: It’s great for us. We’ve purchased a lot at FotoFest. If I had to travel around the world and try to find all those people and meet them and seek them out, I would have neither the time nor the resources for such. But happily FotoFest gathers them here and all we have to do is keep our eyes open. We’ve been very lucky because we’ve purchased people early in their careers. For instance we purchased Simon Norfolk at one of the first FotoFest’s. Artists tend to remember when you purchase them early. Once they are famous and you purchase their work, it’s not as interesting for them. Consequently we’ve built a relationship with Simon by continuing to follow his career, leading recently to a purchase-gift-arrangement for a large group of Simon’s photographs. We were thrilled – he was thrilled.

Luis González Palma’s career started at the 1986 FotoFest. It was a huge thing for him and many others have gotten their start by having shows first at FotoFest.

When you can meet people just forming their career and watch them, you can really build some solid relationships, which is what we’ve done. That’s what we’ve done with Robert Frank. We also distribute all of his films, which our Film Department does. And both Joel and Catherine Wagner, same thing. We have serious bodies of their work, which we’ve built over the years. Nick Nixon is somebody else; we’ve built a relationship with Nick and a large body of work over the years. So looking at somebody when they are young is part of that trying to find those people who are going to be the next Robert Frank or Irving Penn or whoever.

EA: I have a photography book from 1976, ”Women See Women,” with a photograph by you in it. That is yours, right?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: I was still a photographer then. I was a photographer through about 1980 and then it was just a matter of time and energy. I was spending more time doing the curatorial than I was the photographic. I actually gave all my equipment to the Museum school which they tell me one my enlargers is still there. So, yes, I was a photographer.

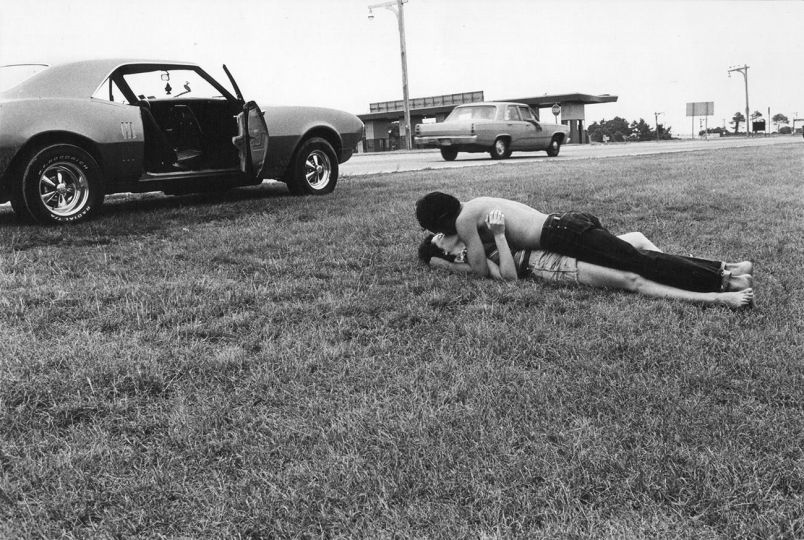

EA: Was your work all street photography, as in the book?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: It was street photography and I photographed my family. It tended to be toward the quirky wherever I found it, whether it was on the street or in a particular way a tree grew around a fence. I remember one of my early photographs was this weird way of boiling eggs split apart, formed this kind of intricate web of egg white in the boiling water. I’ve always been interested in the quirky so that’s what the pictures tended to be.

EA: Is there anything you would like to add in closing?

Anne Wilkes Tucker: Two things I would add. If I’m going to talk about mentors, and I’ve mentioned John and Nathan, I really have to mention Peter Marzio who was my Director from 1982 to last Fall 2010, when he died suddenly.

I really want to mention what a difference Peter made. When he came in 1982, the endowment was one million dollars, and when he died, the endowment was one billion. And that doesn’t include building two new buildings, finishing the Cullen Sculpture Garden, all the art we bought, or all the exhibitions that we did. So if I’m going to mention mentors, I’m going to mention Peter, because he was major. He understood the importance of Photography to the 20th century. He was just so supportive, there is no way I could have done research on Brassai for four years and research on Japanese Photography for five years without the generous support of the Museum. I got the credit, but he’s the one who stood behind us all and made it possible. He understood and he got it.

I had plenty of invitations to leave the Museum, but I always told Peter, “You stay, I’ll stay,” because he was such an extraordinary man and visionary Director, incredibly supportive of his staff and of all of us in terms of staying with us. Some of these projects had really up and down rides, not all of them came easily, and Peter stayed with us. If we were in it for the haul, then he was in it for the haul. He was such a brilliant man that he was really great to go to when you were struggling conceptually with something, to bounce ideas off of him.

The other was Director here, William Agee. Bill was the one who hired me. The delightful part is he was so supportive of photography. He grew up next door to Barbara Morgan (American photographer and co-founder of Aperture Magazine) and had seen photographs on the wall, and knew people who regarded themselves as artists who were photographers, from his early age. Before he came here, Bill was at the Pasadena Museum of Art where he also acquired photography.

Both men were wonderful; it’s just that Peter was here so much longer.

Exhibition

July 3, 2011 – Sep 25, 2011

Helmut Newton: White Women • Sleepless Nights • Big Nudes

Museum of Fine Arts

Houston