There’s work to do. Star-work, but earthbound all the same.

– Richard Powers, The Overstory

We are in yesterday and a Nikon F leaps through the air in a caper between the drunk and the briefly gorgeous in an otherworldly place right at the beginning of Hamburg’s Reeperbahn. It is populated by individuals from the lower rungs of society, who anyhow are living their lives to the fullest on some higher grounds of hell-bent, organic existentialism.

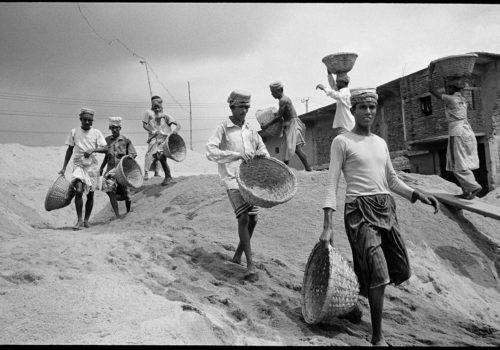

“It was an absolutely fantastic bar. It was packed with people and nothing was noticeable from the outside. It was such a huge difference. And the volume was like walking into a wall – with Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Little Richard, the Beatles, Stones of course, and Jonny who sang ‘Junge, komm bald wieder’ on the jukebox,” recalls the owner of that camera with an immensity of warmth. As a young man he did come back to photograph the regulars there for the remaining years of the 1960s. Half a century later there is a (so-called) gentrified hotel where this bar once was, on the other side of the road from the Zeughausmarkt Square. Still and all, Anders Petersen’s precious family of nocturnal animals has a permanent place in his legendary photobook from the 1970s, the forever gorgeous Café Lehmitz.

Anders Petersen had previously been roaming the streets of Sankt Pauli in 1961 together with the young wild things of Hamburg as a seventeen-year-old. However, when he returned in October 1967 – blessed by his teacher Christer Strömholm – the only one left from his much-loved tribe of outsiders (many had not survived this unrestrained lifestyle) was Gertrud, a lady of the night who suggested that they should meet up in the wee small hours the next day in a place new to him. Petersen fell in love with the Café Lehmitz clientele right there (that his friend was two hours late did not make much difference).

“Is it any good?” asked a destitute king of the Lehmitz crowd, pointing at the Nikon F that the photo student had left on the table. He told Petersen that he of course had a much better camera, a Kodak Retina, whereupon Petersen countered that he had owned a Kodak Retinette when he was little. “And we drank to that. And we continued to toast and after a few pilsners we went to the bar for some stronger stuff, Ratzeputz. We started dancing with some lookers and it was then that I discovered that the camera was gone. It was dreadful. But shortly afterwards I saw it at the other end of the bar, hurling in the air. They threw it between themselves – poof! – and took pictures of each other. I was a little plucky after all the drinking so I danced over to them and insisted that it was my camera, so they could just as well take a picture of me, and that made some sense. They took the picture and handed over the camera – but then I held on to it.”

During this first trip abroad as a photographer, Petersen took a picture of a Hamburg train window on which someone (in German) had scratched: “I love you. Do you love me too?” This has always been the prime motivator in Petersen’s highly subjective and exquisitely tender photography – documentary as it is in some sort of way, yes, but always centred around these auspicious circumstances of love, curiosity, transformation and altered realities; a take-the-sad-songs-and-make-them-better intensity rooted in his urges of longing and belonging, and always this validation of others. Petersen’s work is about the knowledge that we are all full of shit and yet full of wonder, if we are up for it, if only we are seen.

Luis Buñuel (through the handsome editing of Jean-Claude Carrière) described this specific force in his biography My Last Breath in 1982: “When we were young, love seemed powerful enough to transform our lives. Sexual desire went hand in hand with feelings of intimacy, of conquest, and of sharing, which raised us above mundane concerns and made us feel capable of great things.”

“Photography is not so much about the cerebral for me, it is more about intuition. And then it is actually about this matter of how you are and how you move. It is very, very crucial,” says Petersen. “For example, when you approach a group of people that you don’t know, then it is important to go straight to the nitty-gritty and tell them that I am Anders and that I am about to take pictures and why I do it. As quickly as possible. And then you ask more about them, and learn. Because to be with people is also a way to gain knowledge, and to recognise yourself not least, and to find a kinship and a presence in this group. Many photographers make this mistake, and I have also done that: you see something that looks like an interesting picture, and you go on thinking, and then [makes a clap with his hands] suddenly it just disappears. You should not keep thinking and calculating with risks. It is important to go straight on – and to walk straight.”

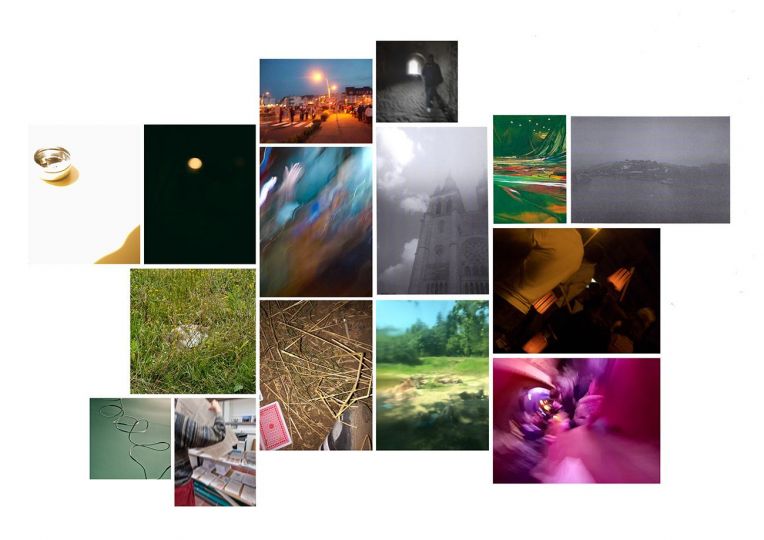

We are in his lab on Stockholm’s absolutely most beautiful island, Stadsholmen, on the opposite side of the Old Town’s touristy thoroughfare with the plasticky Viking helmets. We are in a small corner, underground, next to a black staircase – as narrow and steep and dreadfully exciting as the rear airstair of a splendid old Super-Caravelle – that drops down to a medieval coal cellar which for thirty-two years has served as Anders Petersen’s magical darkroom, where days are spent on perfecting a single print, though he claims (under protest) that no one appreciates that kind of craftsmanship anymore. Binders and binders of his negatives shelve one of the walls, and two silver magnetic boards cover the other walls in this corner. For years these were cram-full of small printouts that were rearranged on a regular basis, images of his recent project.

From late winter 2014 until late spring this year – when the largest exhibition of a photographer ever conceived in Sweden opened at the huge Liljevalchs konsthall in Stockholm – Petersen was busy working on his first in-depth examination of the people of his hometown. It is called Stockholm but should obviously have been titled Stockholmers – for geography is of little interest to him; it is the people, their stories and private spheres that make the city great according to Petersen. “One of the most difficult things to do is to photograph in the city where you live, in any case that’s how it is for me, and I needed to give myself assignments. In this project I gave myself a task several times a week to go to a new place with the camera.”

One of those many places was the suburb of Fisksätra, and in Stefan Bladh’s hour-long documentary on Petersen (recently shown on Swedish state television SVT – a shorter version is looped in a room in the Stockholm show) you find the photographer catching the image of an older woman with crutches who is reading a newspaper on a bench in a cheerless shopping mall. When she becomes aware of Petersen and his tiny Contax T3, he makes a hush sign with the finger to his mouth and the lady mirrors the gesture and grants him the picture he is after. He takes her hands and kisses them. The loveliness and the candour. This is Anders Petersen at work.

Orson Welles famously remarked that one of the truer meanings of the word amateur is someone who loves. “I am in that sense an amateur, absolutely,” responds Petersen. “And it is not about having been working as a photographer for fifty years, it’s just about being – and then you are an amateur. To put yourself in situations where the original, the primitive get an opportunity to be present. It is on the earth, on the ground that the creative vitamins exist, not up there among the clouds and the angels. Away with the head! Throw it away! To be conceptual is not my temperament. I prefer to be at speaking distance, and to be a part of the circumstances.”

“The funny thing about Anders is that he is really never getting finished. Constantly new pictures to be taken. As a client you have to keep a cool head, accompany this talent on the journey. Anders, with his warmth and intelligence, has put many a people at work during these years,” tells the Director at Liljevalchs, Mårten Castenfors, who reveals that he had just seen the Anders Petersen retrospective at Fotografiska in Stockholm in 2014 – which followed the Paris retrospective at the Bibliothèque nationale de France – when he decided to produce and host a Petersen show-in-the-making, Stockholm.

“I am personally a minimalist, a sparse boy who travels between home and Liljevalchs every day and sees very little of Stockholm. This is a unique insight into the other Stockholm, which I have no idea about,” Castenfors reflects. “Anders has really come close to a Stockholm that also exists. And when I see the photographs I sense, regardless of the motif, the earnestness and sympathy for what is in front of the lens. And if I look at the exhibition it has become an extremely interesting document about the diversity that exists in today’s Stockholm, highbrow as well as lowbrow, life in the suburbs as well as the Nobel Banquet. Nothing is missing, and for that I am more than grateful.”

That’s the way it is with Anders Petersen’s photography. He extracts what is us – and with that, what is him. Stockholm dwells (more than anything else he has done) in a time-and-space area that is rare, peculiar and still very real, as if he wanted to stimulate a Verfremdungseffekt in these pictures. “Exactly, that is how I see it too. You walk around the streets, and are a little lost. Thus, there are so many impressions that attack you – from the top, from the bottom, from the sides, from behind – and this is to some extent the diversity that I want to show in this selection. It is too much of everything. It is difficult to see, you have to be very focused to be able to distinguish, and I have tried to just opt for the parts and to put them together in a new way,” Petersen replies.

Stockholm is a city where you can walk around for hours without meeting the eyes of another human being, and for a decade without ever receiving a compliment, and probably for a hundred years before someone invites you home – as Susan Sontag argued in 1969, “Being with people feels like work for them, far more than it does like nourishment.” For a person who has always been interested in “what’s behind all the fucking closed doors”, Petersen uses his camera in genius ways to unlock all sorts of gates and inhibitions.

He explains that with Stockholm he lured himself to be surprised all over again. “Innocence has a lot to do with life and photography. Photography is not about photography but about completely different things. Above all, it is about adventure and, depending on who you are, it is about looking for an answer to the questions that lie in wait. ”Something very near in sentiment to what Robert Louis Stephenson observed in his travel memoir The Silverado Squatters (1883): “There are no foreign lands. It is the traveller only who is foreign.”

“Without knowing about this quote, this is exactly what I think, no matter where we come from and our cultures,” he says. “The more you are going around and meet people, you discover that we are a large family and that we are not so different. We are family members, we are relatives the whole bunch, and that is the very underpinning of everything. And if you have that idea it is fantastic to see how many doors are being opened for you. And it is important that the doors are opened because I am not so interested in the surface or what people represent, but mostly what is inside – for example, our longing, our thoughts, our questions. Other people’s questions are also your own questions. You should remember that and not be dazzled by the outside too much. In order to get on the right track, you have to enter. And when you come in things are happening.”

One such image, and for the Stockholm project one of the not so many pictures photographed in landscape mode, shows a woman and her dog in what looks like a weird internal staring contest (teeth shown as to trigger aggression), but Petersen assures that they had a lovely time together over a fika (Swedish coffee break) in the woman’s home. “If you shoot in Rome, Saint-Étienne, Madrid or Barcelona, it is a completely different matter because every street in these cities is like a scene. You really only have to hold up the camera and the pictures jump in like rabbits. But here you have to go in where people live, and there it happens. This is the case in Scandinavia, especially in Sweden. It is rather little that is actually happening over a whole year, but there is a big difference in the summer months.”

There are quite many pictures of people on their balconies – a remark that takes Petersen by surprise. He figures that they are the outcome of the need for daylight, pure and simple. And there are many pictures of people with tattoos, however it is not the tattoos as such that fascinates him, “it’s just that it is so very common. Sweden has the largest number of head tattoos in the world, this I know as a fact. Previously it was a mark that you came from the prison, that you were a criminal or a sailor. I have photographed in a prison and there the tattoos mean something. Today they mean very little, it is just a decoration, a fashion above all.”

It is no secret of course that Petersen photographs people that he can identify with and that his photography is a kind of enamoured family album. In his book The Ascent of Man (1973), following his BBC television series of that year, Jacob Bronowski writes that “We are all afraid for our confidence, for the future, for the world. That is the nature of the human imagination. Yet every man, every civilisation, has gone forward because of its engagement with what it has set itself to do.” Perhaps no other picture represents Petersen’s quest for companionship without the rosy narratives as much as his augmented self-portrait Lilly and Rosen (1968) from Café Lehmitz, in which a bare-chested man with a girl tattoo is seeking comfort in the bosom of a woman who accepts him with a heartful laugh. This very tender but in no way uncomplicated image is also the face for the Tom Waits album Rain Dogs (1985).

A Stockholm picture from a restaurant kitchen with a parade of pickled cucumbers just out of the brine is very Petersen, and even more so are his individual snowmen, these mourning human figures that are eighty per cent air. “There is something that I think is so obvious in Sweden and that is the melancholy, the Scandinavian melancholy, which is poignant and very beautiful. And there is a lot of it in the snowman, you see. Their lives are short. I had a snowman standing outside the door here for four days, and then it languished away. But the snowman that I photographed on Katarinavägen has a twig mouth so it smiles a bit obliquely.”

The animals and the animalistic are part of everything in his work, and Stockholm is no exception. “The primitive is a bit ‘back to basic’. With primitive I do not mean to go to any extremes – if you are hungry then you eat, if you want to say something you say it, if you are angry you are angry, if you are sorry you are sorry – it is about trying to approach the simple things, it isn’t more complicated than that. And you show it, you don’t hide it. It is a way of dealing with things in everyday life and in the work to be like that. It does not mean that you are in any way strong, you are never strong enough. It is bullshit when people say that you have to be strong. In fact, you have to be weak enough because it is then that you open up for opportunities, both for yourself and for others, by showing your fear, your anxiety, your questions, your vulnerability. And I think that this is a fundamental part of being present in what you are photographing.”

Anders Petersen has a metaphor for what is making his photography so distinct and that is the example of the pyramid. “By that I mean that from the beginning you are at the bottom – there you have your friends, food, good wine – but none of that gets you to work as a photographer. It is wonderful if you have a security, but you have to give away the security, scale it off to arrive at a confidence in yourself. You must believe in yourself. Who are you? You must have an idea of why you do this. What is important? The more you peel the closer you get to the capstone. You sharpen it and finally you are so feverish, and that is when you can go on. And then you are a bit dangerous.”

“I have seen so many different types of photographers over the years, but what unites them is usually that they are a bit shy and cautious people, not so outrageous – that they are curious of course, that they are patient, a little stubborn, that they are searching and searching and not giving up. But then it is another thing that may not be so nice when I think of the people I know, and whom I have seen photograph, and that is that they are so incredibly sharpened and focused that it is like they are in a small bubble. They are only inside the creation in some way, and it is a phenomenon for better or worse because it can mean that they are not particularly sensitive, or they can even be rather ruthless. If you look at some of the war photographers, it is a necessity that when they hold the camera it becomes a protection so that they dare to do things. But that also applies to street photography. You can never trust what a photographer really says. That is typical for photographers, they have a bad vision, they see what they want to see.”

Twice before and long ago has Petersen been working on a photographic project on his hometown. In 1969 he and his friend Kenneth Gustavsson (with whom he started Saftra, a famous cooperative of photographers, the following year) made a work together with two very gifted architects at the Stockholm City Museum called The City in Return, an exhibition that delineated both the city’s slum areas and the ravages of a Social Democratic warlord Mayor whose antiseptic demolitions were schemed to erase the better part of Stockholm’s history, vitality and great beauty. And then again in 1973 when he photographed merrymakers at the uncharming amusement park Gröna Lund, which is also the title of his first photobook since all the seven publishers whom Petersen approached in Sweden turned down his pictures from Café Lehmitz.

The large and lush Stockholm assignment very modestly began in a café at the corner of Stortorget in the Old Town (the Grand Square where the Stockholm Bloodbath took place in 1520) when Petersen’s friend Angie Åström came back from Paris with an idea. She had been living in Paris for several years and reflected how common it was that the exhibitions in this city depicted its people in various ways. At the opening of Petersen’s retrospective in the Bibliothèque nationale’s glorious 17th-century building in the late autumn of 2013, she “encountered residences from all over the world, but Anders’s hometown was missing on this map of pictures”.

“The reason that I contacted Liljevalchs about a request for the Stockholm project with Anders Petersen arises out of how I figured a similar series of pictures would materialise in Paris,” explains Angie Åström. “The large range of images was not the intention from the beginning, but the renovation and extension of the art gallery led to the continuation of the work with the pictures for four years. It was in this way that the Stockholm project started, and five years later I have not tired of his pictures or his personality. On the contrary, he is even more interesting as a photographer today. Anders’s idea of a diversity of images instead of the individual photograph generates entirely new ways of thinking.”

A bit over two thousand Tri-X negatives were scanned for the Stockholm show. “I made contact sheets and from these I chose the negatives to be scanned, and then I selected too much because you never know how it might work out. A very idiotic process really because it takes such a time and costs money, but that is how it is to be analogue and at the same time insist on doing digital things,” says Petersen. “From these we selected about eight hundred pictures and processed and copied the scanned files much like you do analogue in the darkroom. And then we made a selection from it, seven hundred pictures, but it was too much.”

The around five hundred contrasty printouts do look fantastic, especially the big ones presented in blocks and nailed to the walls in the major of the eleven rooms at Liljevalchs. “The great work with Stockholm was actually done by Erhan Akbulut. He is a digital editor who has worked for Magnum in Turkey, a maestro who I met in Istanbul. Now we have made five books together. He sits with the newly-scanned file and I sit behind and scream ‘Lighter, no darker!’ It is an exhausting and demanding process, as you understand, especially for him. I did a residence there for two weeks and he developed the films and made contact sheets and I saw that he had a feeling for it. And then he came to Stockholm, and now he lives here and is together with an adorable Norwegian.”

Anders Petersen grew up on the posh Lidingö which is one of the islands in the inner archipelago of Stockholm. When he was fourteen the family moved to the city of Karlstad in Värmland, a part of the country that Petersen is very fond of and a province that wrenches Sweden’s largest lake, Vänern. When he was seventeen, Petersen’s parents wanted to do something about his bad results at school so they sent him to the affluent Hamburg-Groß Flottbek district in order to learn German. It did not work out so well with his wealthy host family whose garden he was expected to maintain.

Soon enough Petersen found his peers in the disreputable underworld of Sankt Pauli. “It was a gang that came from England, France, Italy, America – and then I met a Finnish girl, Vanja – and they were not god’s best children but I liked them very much,” says Petersen with a lot of affection in his voice. “I got the whole package. And this package included companionship and a kind of curiosity on life, unfortunately also drugs and not entirely legal things. It became very clear to me that alone you are nothing, it is with friends that you can create a platform for something worth standing for.”

When Petersen shortly returned to Karlstad from Stockholm to write for the morning paper Nya Wermlands-Tidningen, he had no intention whatsoever to become a photographer. One day the young man was waiting to get his hair cut. Since Petersen has always liked crosswords he flipped through a women’s magazine when a minute photo of a snowy Parisian cemetery grabbed him with a bang. “I was very affected by the picture, that the photographer managed to interlace this idea that the dead were socialising at night when no one was seeing anything and that the footsteps revealed them. It was so poetic, so loaded, but I had no idea who had taken the picture.”

“This thing with being a photographer has never really interested me,” he implies. “I was painting and trying to write before, but I never really got close. When you write you are usually very alone, and same when you sit on your chamber and paint. In photography it is so wonderful that you can be in the middle of a situation with a lot of people and you can talk, you can share views, there is a mutuality in it, and at the same time you can photograph without making a big deal of it.” The next year in Stockholm, in 1966, Petersen met some photographer friends. One of them was Kenneth Gustavsson who – much illegally – provided him with a key to Christer Strömholm’s Photo School whose darkroom Petersen (still much illegally) began to use each night between twelve and four.

Eventually Petersen was caught one night when there were loud bangs on the door to the darkroom. It was the great man himself – the photographer of the metaphoric 1959 picture of the Montparnasse cemetery, where the tombs have begun to rattle and ghostly tiptoe steps make it through the snow. “I was convinced that he would notify the police so my confidence in him grew when he instead just asked me if I wanted to begin at the school.” Petersen was twenty-two years old when he met Christer Strömholm for the first time that night.

“He had already when I started at the school, and how I started there, given me an idea of how to be and how to trust someone, and see someone. So, he not only became a teacher for me or the principal at the school, but also a close friend I would like to say. He also became a deputy dad. I was disconsolate when he died, it was horrible. He had his stroke in 1982 but then he continued for twenty years, and he trained. But his photography was not the same. He focused on stationary motifs, Madonna pictures, symbol images and such. No outreaching photography, it was difficult with the stick. But he went on.”

There was language teaching, history teaching, social studies, writing and photo history continuously at Strömholm’s Photo School. “I remember the first few times when we were at Klippgatan 19C, when we sat there and he initially just talked about his photography. This was not a man of many words, he was more Hemingwayan. It was short sentences and his stories were more like statements in which he mentioned what he had done. And his presence on the scene was … yes, it was electric in some way. We were quite smitten. Especially when you saw his pictures from Poste Restante [1967] which is a fantastic collection that tells a lot about his life and upbringing and about his fears. And he shared this with us, briefly and distinctly, and said names that showed that he knew things. But then I had the old habit that I used to come in early, already at eight, and there in the windowsills lay his pictures in 18 x 24 size which had been copied during the night.”

“And I looked at the pictures that lay there and it was an incomparable experience. I understood that this was not just a guy who was anyone but a narrator who also made pictures, and when you pulled them together you got Christer and his dreams, his magic and visions. He grew enormously. Another thing that was so nice with him was that he was so adventurous, he had such an appetite for life, even after his stroke. I remember, I went in his Volvo and we were somewhere in the Vasastaden district and suddenly he said, ‘Did you see? But didn’t you see the legs?’ [Petersen mimics Strömholm’s broad Stockholm accent]. He made a U-turn and drove towards the traffic and back and crawled forwards – and there came a girl with very nice legs and high-heeled shoes.”

There were new assignments to solve each week at the school, “like ‘white egg against white background’, which was certainly good but not so fascinating. And then I asked him if it was okay if I went to Hamburg to photograph my old friends, because they had something that I did not have with my bourgeois background. So, it was both a protest and a kind of idea of community that I wanted to photograph.” This was ten years after On the Road (1957) with Kerouac’s gallery of odd ones out, “the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time”.

Now six years older, Petersen returned to Hamburg only to find that his desirous Sankt Pauli family was gone – everyone except Gertrud who he found at the Scandi-Bar, which was located on Seilerstraße (a parallel street to Reeperbahn), “a place that opened at twelve o’clock at night, and it was full of striptease stars, transvestites and everything else who used to come there. It is very interesting. You learn a lot about life.”

Gertrud mostly knew him as a painter since he used to sell his postcard drawings at the Fischmarkt every Sunday. “She did not like the idea of me being a photographer, but after three pilsners she changed her mind and said that I could come to Lehmitz at one o’clock the next night.” Though Petersen couldn’t have had a more celebratory start at Café Lehmitz, he did not at first realise what a treasure trove for situational photography that he had run into. “No, no, not at all. This was just a place that I came to, but then I liked the people more and more when I got to know them, and we got along really well. I had to convince them somehow. They were exceptionally kind and decent people,” he answers.

“They were people affected by circumstances in different ways. Much like in Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz [1980], a fantastic effort, with the protagonist coming out of prison and is about to start a new life. He is a sensitive, living person, and he has to conduct himself all the time. And it is so difficult. It is through his eyes that the film illustrates various things. There are wonderful films that Fassbinder has done. Even his last film was strong, Querelle [1982], the one about the sailors written by Jean Genet.”

There were several men just like the fictive Franz Biberkopf in Petersen’s new Lehmitz family. “I am a small guy. I was no threat to them, and above all I fell in very well with Lothar who was a fellow who had very great respect. There were really only two things I can say that he honestly liked: his dog and Ramona. Ramona was actually called Karl-Heinz. At the age of nineteen, she changed her name and started with hormone injections, and she was doing that while I met her. Sometimes she was a man, sometimes she was a woman, and then she was a stripper at the Roxy-Bar on Große Freiheit. And Lothar had done something terrible and had been in prison for ten years. He had a gentleness in the midst of everything that I believe opened for a kind of mutuality.”

Lothar, his black poodle and Ramona are also featured in the last section of Anders Petersen’s monograph that came out in 2013. When Petersen returned to Hamburg many years after Lehmitz, Lothar had become a manager of a neighbourhood brothel business in Sankt Pauli. “In the courtyard building he had three older women who worked there, he himself lived in a small outhouse along with one of them. And he had a vegetable patch because he was very keen that everyone should eat well. He cooked for them.” Lothar was one of the Lehmitz jailbirds who convinced Petersen that he should photograph the unseen life inside a penitentiary, an idea that resulted in Petersen’s threefold institutional series (and books) about people in a prison, in the eldercare and in a mental hospital.

Anders Petersen’s first solo show was at Café Lehmitz in 1970. Three hundred and fifty photographs nailed to the walls, and the object of the game was that anyone who recognised him- or herself in a picture was free to bring it home. Later that year, Petersen showed his Café Lehmitz pictures in Stockholm with sounds from the Hamburg bar filling the gallery. (Liljevalchs has a slideshow room with sounds from Stockholm.) But Petersen had to wait until a fortunate meeting at the Rencontres d’Arles in 1977 to get his work recognised – Café Lehmitz was finally released in a German edition in 1978, and the following year as Le Bistro d’Hambourg. A Swedish print appeared fourteen years after this masterpiece was completed.

Much of the 1970s was a difficult time for Petersen. He tried to photograph for some magazines in Sweden and, as a rather desperate measure, attempted to become a man with a movie camera during his two years at the Dramatiska Institutet (Stockholm University of the Arts). “I was quite sad then and figured that film is still quite close to photography. But they are two completely different things. At that time, I wanted to go out with a small film camera and film in much the same way as I photograph. But it was very difficult because it requires a whole staff of people to take care of it, and that is crazy and not my thing. I am more of a solitaire who builds relationships.”

Peter Ustinov is the only light (beside David Bowie) in Hermann Vaske’s misdirected documentary Why Are We Creative? (2018) in which the British actor delineates the case of Albert Einstein who belonged to a yachting club in Zurich, though he preferred to take out his jollyboat on days when there was not even a breeze: “But Einstein, when everything was reduced to the fact that there was no wind, began to notice things he would not have noticed had there been wind. And, therefore for him, it was most important to go sailing on an unpropitious day. He never won any regattas in his time, but he did notice all sorts of things, which eventually led to the ‘Theory of Creativity’.” And that is how Anders Petersen photographed his institutional trilogy (1981–1995) – with the spark of life.

“That is a fairly striking image,” Petersen replies, “because it is about taking the time, both as a human being and a photographer, and not looking for the spectacular and dramatic situations. Because if you do, you will end up in a photography that easily depicts the superficial. I am looking to find a photography that unites people instead of isolating them. I want to obtain a photography that people can identify with and recognise themselves in. And when it comes to people, there is no better way than to just sit down and talk with them, it’s that simple. One must absolutely have a curiosity that is true and correct, otherwise it doesn’t work.”

Although the Nobody Has Seen It All series from a mental hospital was the last in the trilogy of confined people, Petersen ran into difficulties when he was getting too emotively involved with the patients. “It is a creative act when you start shooting and are in the middle of everything. Sometimes I have been too close and standing with both feet in the situation, and that is not negotiable. And I made many, many mistakes then. I became too emotional so I couldn’t handle it visually. I usually come back and give away pictures but I could not do it then, something was absolutely wrong. I have learned to stand with one foot inside and the other outside the situation. I am like a rubber band so that I have an eye on what is happening and then I don’t get so emotionally engaged.”

Petersen talks about photo history as a family tree where he belongs to a branch of photographers with whom he can easily recognise himself. “First, we have Strömholm with his persistence, sensitivity, vulnerability. And then we have Brassaï, the Parisian photographer who came out in the 1930s with his book Paris de nuit. And then Weegee. I especially like Naked City, which came out in 1945, it is such a strong account of its time. Then we have such greats as Lisette Model, Diane Arbus, Nan Goldin today, Robert Frank of course, and Daidō Moriyama who now receives the Hasselblad Award.”

What is fascinating about Moriyama’s work? “His waywardness, his amateurishness and that he insists all the time, he releases book after book. Overall, his photography is about his life to begin with, but also about our time. We had an exhibition at the Rat Hole Gallery in Tokyo, and then I was invited to his little place in Shinjuku above a bar, a room with a small sofa. Everything is small. There he puts up his latest pictures. He asked the people in the bar to come up with whiskey and pilsner, and then I sat there talking with Daidō and it was very, very sympathetic. We drank whiskey in a very special way as they do in Japan, one part Japanese whiskey and one part sparkling water.”

“This particular episode was in 2008 and then we talked about how it is with students. He himself has had a lot of workshops and he had almost like a school in the late 1970s. He told me that it became too much for him in the end, because the students became like his children and it was difficult to take care of everything. In Japan, it is almost in the national character that it is very passionate – if they are into something, they are into it one hundred per cent. We talked about how important it is to learn from a younger generation and how a relationship with other people can develop. And then I thought about my relationship with Christer Strömholm. It is funny, the pictures that Moriyama took in the 1960s are very similar to the pictures that Christer took in the 60s, but they did absolutely not know each other.”

He narrates an episode during a residence in Rome when a fan-turned-stalker silently followed him for a whole day, trying to mimic his shots and catch some of Petersen’s genius. He loves to teach, though – “They think that I come there as a fucking teacher and they are completely wrong! I am the student! I learn what a younger generation is doing,” he says smiling – but he has cut back on his workshops to only a few times a year. “Mutuality is magical,” says Petersen, “it is what defines life and serves as a springboard into other circumstances and situations.”

“It was tough to do Café Lehmitz because I had so many slurs from many parts in Sweden, from the political right and the proletarian people. But one has to stay clear of what others think because it is so devastating. I have my vision and it is completely clear and I know why I do things. And it is obvious that you are not immune to criticism, but you still have to be equipped for it. You learn to deal with it after a while. In France, there is a completely different sense of knowledge than in Sweden, and they can handle the information flow in a completely different way. I try to keep everything as clean as possible and that is the only way. From Lehmitz until today, there is a red thread that deals with reciprocity and a presence in people, where I want to be a part of them and not someone from the outside, whether it is a princess or a homeless person.”

As for Stockholm, Petersen operated much like the old telecom tower of the 1890s, from which 5,500 wires were suspended over the city in order to make a connection with the Stockholmers. Everyone he has connected with is – to quote William S Burroughs in Queer (written in the 1950s) – “like a photon emerging from the haze of insubstantiality to leave an indelible recording”, it’s just that “insubstantial” is never the right word for the individuals in Petersen’s photographs. Whatever these Stockholm people are up to they are quite remarkable. In a picture someone has been drawing a heart and written “I love you” four times without even begging for something in return. Though life is far from perfect, these pictures are.

Somewhere at Liljevalchs is a photograph that Petersen has taken of his notice board at home. It shows (among other things) a press clip with a picture from Café Lehmitz and a cropped image of Robert Doisneau’s Coco (1952) in his bowler hat, and that smile as wide and peculiar as the one on the fugacious snowman on Katarinavägen. Stockholm stands, in a host of ways, with one foot inside those past ages and together with the curious characters who made them real and fulfilling. Half hidden behind the flap of the inner cover at the end of the catalogue is a greeting to Lilly and Rosen, as lustrous, melancholy and life-affirming as everything else in this show: a couple’s tender caress on a bed, a man’s head against a chest, again – and then (you just know it) the whispering words of the receiving naked body, “I love you.”

We are in today and Anders Petersen sees what he wants to see.

All the somebody people.

Tintin Törncrantz