From our archives – December 19, 2016

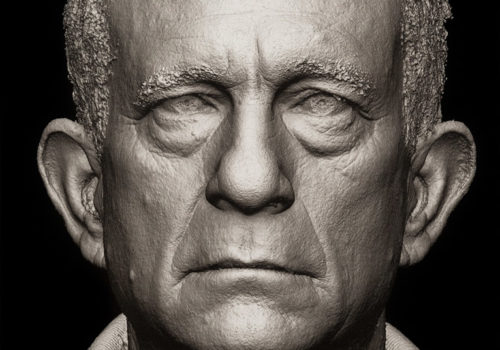

His name: Daniel Wolf. He was one of the great dealers in photography during the 70s and 80s. Most importantly he was the originator of the Getty Museum’s acquisition of some of the most important photographic collections in the world, such as those of Crane or Wagstaff… The site Arterritory.com has just published an interview with him by Una Meistere. Here it is.

The collector is a critic

Collectors sometimes compare the process of forming a collection with living a separate, parallel life, with both lives interacting and adding to each other. Viewed from this perspective, the American collector and dealer Daniel Wolf has 15 lives. He has been collecting for forty years and currently owns 15 different collections, from 19th- and 20th-century photographs, contemporary paintings, Chinese ceramics, quartz crystals and pre-Columbian art to late-1960s Warhol. Wolf also owns one of the largest collections of interior objects made by 20th-century American designers and architects, including pieces by Frank Lloyd Wright, Greene & Greene, George Mayer and Charles Rohlfs.

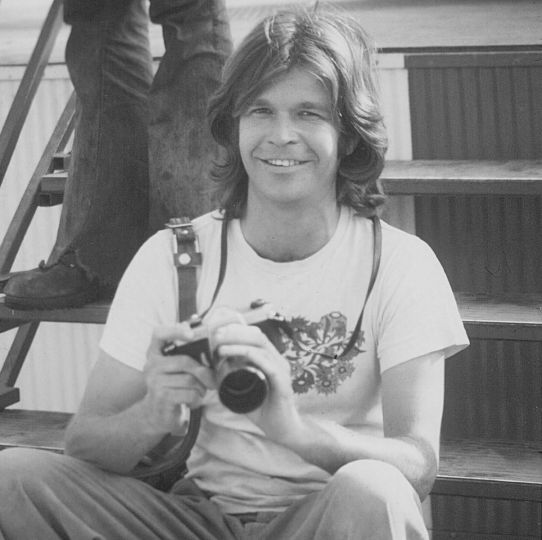

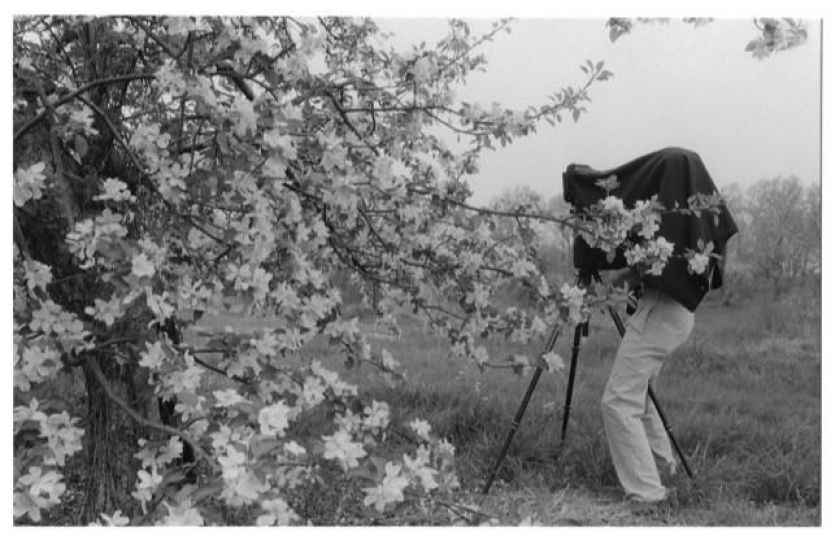

Wolf is undeniably a legendary character. He began his career as a dealer of 19th-century photographs and opened his own gallery in New York City in 1977. He later turned his attention to contemporary photography and can be said to have helped give rise to the market for photography. Compared to painting and sculpture, the prestige of photography in the 1970s art market was very low; only a couple of collectors actively worked with the medium, and only a few museums bought photography. At the time, Wolf says it was hard to sell a photograph for even 200 dollars.

By 1983 Wolf was considered one of the most influential photography dealers in the world and played a large part in developing the Getty Museum collection. Today, he works as a private dealer specialising in photography, Ancient art and 20th-century art and design.

It was recently reported in the media that Wolf and his wife, the artist and architect Maya Lin, have bought a former jail on the banks of the Hudson River in Yonkers, on the outskirts of New York City, where they plan to open a private art space. At the time of this interview, the building was still under reconstruction and Wolf was impatiently waiting for the moment he would be able to see all 15 of his collections under one roof.

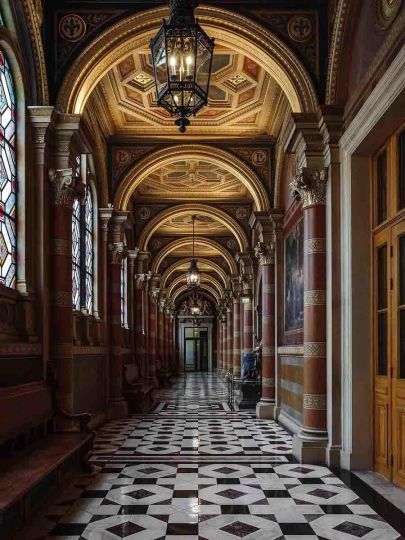

Our conversation took place in October 2015 in Wolf’s apartment near the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. He lives on the top floor of a historic early 20th-century building. The living room is decorated with furniture by Frank Lloyd Wright and pieces from all of Wolf’s collections: paintings, ceramic dishes still displaying their auction numbers, giant quartz crystal “plates” on the windowsills and so on. The only thing one does not see is photography: “Photography for me is not on the wall. It’s in my hands. It’s in a book. I don’t like photographs as decoration. I prefer objects to live with.”

The sun is shining, so we converse out on the terrace. New York throbs down below, the wind is blowing leaves around, and Wolf is dressed in a well-worn jacket missing one button. He looks like someone who no longer has to prove anything to anybody. He has exactly as much time for our interview as it will take for us to get cold outside, he says with a laugh. Richard Prince, that superstar of the American art scene, lives across the street. He has a superb collection of art, says Wolf. One of the best he’s seen recently. Very intelligently and smartly developed. Wolf adds that he recently spent a week in Rome, which he devoted entirely to Renaissance painting. He gazed at paintings all day long. He believes there is no difference between collecting in the Renaissance era and collecting today. Collecting has always been closely linked with the ego. “People bought very much, and everybody’s goal was to create the best collection. Constant competition. And it continues today, also in the field of contemporary art. In addition, people are very afraid of buying something that’s different. Very rarely do you see a collection that’s fresh.”

Interview by Una Meistere

You collect different kinds of things: 19th- and 20th-century photography, contemporary paintings, ancient Chinese ceramics, ancient vessels, quartz crystals…. How did it all start? And which field was the first?

Photography…. Oh, no, no…. Way back when I was a child, my grandmother gave me a subscription to National Geographic magazine. Every other issue had a map in it, and I always took the map out and tacked it up on my wall. So, my first collection was National Geographic maps. I was always interested in this kind of grouping of things that have a meaning. So, I suppose it was only natural that I began collecting. I grew up in a very boring place, and collecting offered a bit of fantasy.

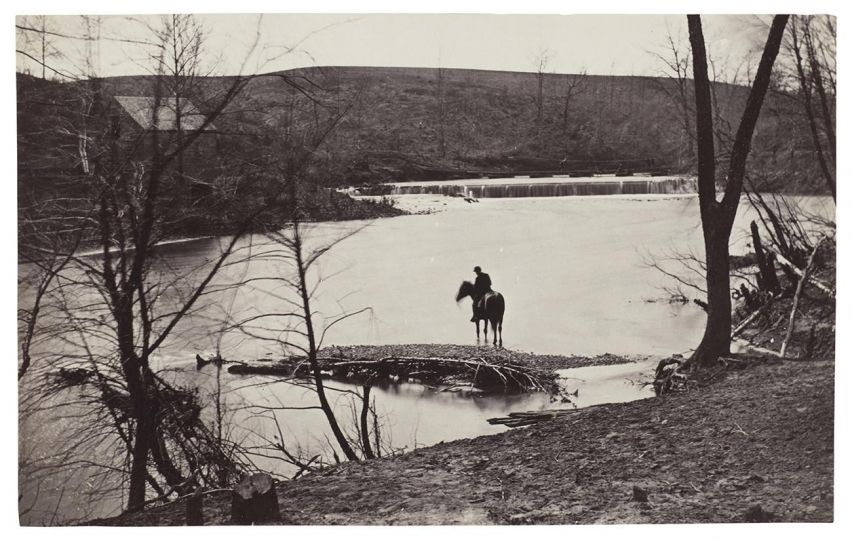

But the very first moment I can remember collecting something was when I was seventeen years old. I was on an exchange program in France. I was living in Brittany, and I walked into an antique store that had some fabulous junk. On the floor were three photographs, done by an amateur named Striebeck in the 19th century. What a wonderful world that was! They were photographs made a hundred years ago, and they were more beautiful than all other prints I could imagine. I just thought – what is going on here? It was like complete confusion. Maybe I don’t remember exactly, but I think that’s how I got the first zap. When you collect something, that first jolt must be there. It’s like being connected to the electric circuit and that circuit never stops. And every next jolt is another connection you have to deal with. Connection is the key word. It’s something that takes over. For example, I’ve looked at African art my whole life. But I still don’t know if it’s junk or a masterpiece. Forty years of looking at it, and I have no idea what it is. I have no connection to it. I can say I like it, but I can’t discern the quality or importance.

I actively collect about 15 things. Anything that connects can be a collection. It’s very intuitive, very organic. And then all the complications of life happen. Why do you collect, for what reason? Is it a passion? You know, all the psychological, social things that are part of this world are very involved. It’s an interesting machine. But it took me forty years to realise that the majority of the art market is about decoration for rich people.

You really needed forty years to realise that?

Yes, it took me forty years. Because to me, art is about art. It’s about an inner dialogue. But for many the purpose is just decoration on the surface…but when you look deeper, there are all sorts of psychological aspects as well…ego, belonging, feeling good to be rich, feeling part of that club. In addition, it’s become an international event. But in the end the art world is a great world to be in. You can travel to beautiful places, see great things, meet fun people. It’s a healthy game. I’m all for it.

Is art a kind of key to a world that you cannot otherwise enter?

Art is very much a key to get into it. Once you’re in the club and can speak the language, it’s a great way to meet people all over the world. And it comes with all sorts of psychological as well as financial benefits. I think it’s precisely the psychological aspect that makes the art scene so vibrant. There are a lot of powerful people in it, and if you assume that everyone is insecure, even the rich and powerful, then you begin to get the ramifications of collecting art.

Looking back, there have been fantastic, brilliant collectors that have spent a lifetime collecting. The sadness in this country, in America, is that you can’t leave a collection to the next generation. The American tax system makes it impossible. If I want to leave my collection, say, to my daughters, I basically have to buy it again. It’s been paid for once, and then the next generation must pay another 50% to keep it. That’s why prominent collections in America are not passed down from generation to generation, as they are in Europe. In Rome, for example, you can still see at least twenty villas that have been in the same family since the Renaissance. And they house wonderful collections of art.

Several large collections have broken apart in recent years in America. Right now they’re dispersing the Taubman collection at Sotheby’s. It’s a beautiful collection. It may not be full of absolute masterpieces, but it’s full of great art. That collection should be kept together somewhere instead of being dispersed.

Collections should be maintained because the activity of collecting is often visionary and thus shapes perception. It also requires timing. Either you’ve got endless amounts of money, or you’ve bought at the right time. I think Barnes is a great example in this country, because he amassed the best collection of Cezanne in the world. He got it before anyone else, he knew it, and he acted on it. He searched every country in the world to find Cezannes. He just did it, and he acted on it…faster and better than anybody else. That happens in every generation. The collector is a very important part in the history of art, because a visionary collector is also a critic.

I spend most of my time collecting, adding to collections, mentally putting together the story.

And in some way you’re always searching for missing links?

Looking, looking and looking. I spend four or five hours a day on the computer. I don’t search, I just look. I go to different auctions, because I collect and deal in such different areas. I don’t really look for anything; just look for something I like. Something that is important. For example, I love French culture, especially 19th-century. And, from the perspective of collecting, in terms of the ability to find things, right now is the right time to focus on this period. Because the contemporary field absolutely dominates right now. Wealthy people have big white walls, and they have to fill them with art. And there are a lot of galleries selling art for white walls. There’s a big white-wall phenomenon going on. As a result, anything linked with 19th-century French culture is really out of fashion, which is very important if you want to be a collector. You can build a better collection when things are out of fashion. You cannot build a collection of something while it’s in fashion, because then it’s very expensive. There is an optimum moment to collect, like buying Cezanne. I may be completely crazy and wrong, but I’m convinced that two generations from now people will be saying: “He bought that stuff for forty dollars a piece. Unbelievable….”

Art today has taken on something of a religious importance, because it’s become priceless. If we think about it, art is priceless – it’s 25,000 dollars, 300,000 dollars, two million…. And people really believe in it.

Do you think that collectors really believe that art costs four, ten, thirty million?

They believe in it…. It’s a concrete substitute for religion, or it complements religion. Or it complements a spiritual something…. I don’t know what it is. But there are powerful forces converging when art becomes really expensive.

Is it true that you helped develop the Getty Museum collection?

You know, it’s hard to imagine, but back in 1982, 1983, when we were doing it, photography was not where it is today. Photography was not part of the natural canon of 20th-century art. There were many great early collections of photography, but in the 1980s the market was in a deep slump and people were pretty convinced that it was going nowhere fast because photography couldn’t get rid of its image of not being really that important. It was like paintings are way up here, and here’s photography way down there. But it’s great to see how everything has changed in thirty years. As I already said, the crucial factor in the creation of all the great collections is timing. There comes a moment when there’s a lot of material on the market and everybody wants to get rid of it. So, this was that moment.

Because everybody thought photography no longer had value on the market?

No, it had value. But the value hadn’t changed much in many years and there seemed to be little demand. Things have highs and lows. It’s always been like that. There still hasn’t been a real low since 1995, but before then the cycle was every seven or ten years. High, low, high, low. Very predictable.

At that moment, photography was at its totally lowest point. There was lots of great material on the market. We didn’t even know how much there was, it was just the beginning of a massive moment – everyone wanted to sell. And then I went to the Getty, and I said this is what I can do because I’ve talked with all these people. And John Walsh, the director of the Getty, said yes. That’s how it all started. We bought 14 different collections.

How long did that take?

From the time I contacted the Getty till the time it was announced publicly, it probably took two years. I travelled all over the world, and the high point for me was the Volker Kahmen collection of almost one thousand vintage prints by August Sander (1876-1964). That was the single greatest treasure trove of Sander in the world, and thus a national treasure for Germany. There was something very powerful about legally taking cultural heritage from one great country to another. It was like, wow…this is serious.

Did Germany not value the collection, that it allowed it to leave the country?

Legally, Germany couldn’t stop it, because exports were allowed if they were not over 100 years old. You just had to pay for a license. More than anything else, it just tells you where photography was at the time. Today it would have been blocked.

The collection I’m actively creating right now has been in the making for over 20 years. It’s a collection of prehistoric American art. I had been collecting pre-Columbian art from Mexico and South America, and, from time to time, I also bought pieces from North America because I felt they were outposts of Mesoamerica and culturally connected in some way. There’s an assumption in this country that there was nothing in America before Christopher Columbus arrived…that it was just apes carrying rocks, and I had to slog through that prejudice for years before one day I had my a-ha moment: prehistoric art from North America is not provincial at all. It’s sophisticated, and the designs on the pottery are world class. After such a realisation, you see things in a completely different way. My interest in the material grew, and I recognised the opportunity to collect this material, like what it was to collect photography the 1970s…very few people were aware of it and there was an abundance of great material on the market with no competition, at cheap prices.

Where do you find these things?

You find them at auctions all across the Midwest and Southwest; some at auctions in Europe, some sold by dealers, some can be found on the Internet. Every once in a while large collections are sold. Earlier, you needed a gallery in order to collect art, because that’s where people went before the Internet. Now I do my collecting on the Internet. It’s great because you can cover so many areas – it’s simply unbelievable how many things have become available in this way. I’m an early adapter to all of this, because most people are afraid to buy something expensive without seeing it first. But for me, if it’s well photographed then I feel comfortable about buying online. If there’s an issue, I call the expert to get tons of advice. Or I ask them to send more pictures. The possibilities with digital photographs today are simply endless, because a camera can store so much information, it’s like seeing the original.

You mean to say that the technological revolution has also in a way changed the art world?

Yes. It’s very efficient. I’m sure that in the future there will be just one platform for trading all art.

What do you think was the decisive thing that changed photography’s status in the art world?

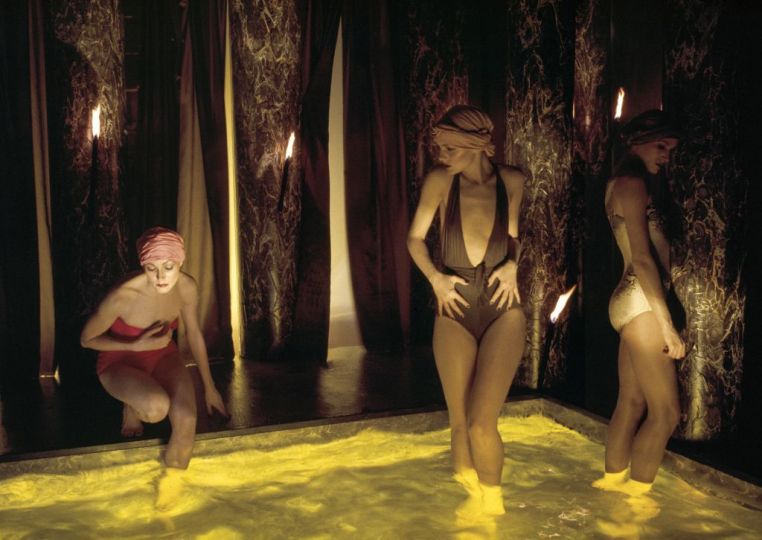

I think the thing that made photography popular – not popular, but accepted – was that big photographs are good on big white walls. Cindy Sherman, Thomas Ruff, Andreas Gursky…you know, they are very great artists, they look great and allowed collectors to “cross over”.

What fascinates you about photography? Susan Sontag once said….

No, please don’t….

You don’t like Sontag?

I think it’s deluding when you look through other people’s eyes….

Why do I like photography? It’s that zap, that jolt. One day when I was seven years old, I took a photograph of a sunset. And I was like, that’s it, baby. That’s the same reason I’m in art. There was a moment, when I was ten years old, when I looked at Van Gogh in Paris and I knew that was it. I knew it would be a part of my life. I think art offered a psychological “something” at the time, too. It gave me a voice when I probably didn’t have one. I needed to identify with something, and photography was my way of being connected…identity, connection – whatever that means in the teenage world. I have no idea anymore, but one thing is clear – once I got that first jolt of photography, it never left me. Even after fifty years I still look at photographs every day. I think about them all the time. Because this is a new field, unknown material still comes out on the market. The photography community is a great group of people. We are good friends, pals, colleagues. There’s a kind of communality because we are all in it for the same reason. I can’t explain what it is, but we are all photo people and that is our language. Maybe that’s something psychological again, because it’s a common language. If you say Watkins, everybody knows exactly what that means….

But not all fields are the same. I love the Old Masters field because it’s really very close and eccentric. The contemporary field is a bit rough for me. It’s serious, with a lot of very smart people dealing with a lot of very smart people. But, personally, for me it’s not about big white walls. It’s about what connects with me. I don’t expect anyone to agree with my tastes. I just keep remembering one thing – Van Gogh didn’t sell any paintings during his lifetime. That’s all you have to remember. I may get it completely wrong in terms of the sweep of history. The people I like may never be considered, not even once, but I love them and for me they are the greats. It doesn’t matter what happens, because I had that jolt, that connection. I keep on looking and learning. That’s all I want.

In the end, collecting is about learning. I learn through the visual; I do not learn through words. I love something spoken by a great teacher, too, but I’m a visual person. That’s how I think, that’s how I assimilate. I don’t want to read, I want to see.

Being open and receptive to new art takes a long time. It took me years before I was able to strip away all the bullshit layers of my own prejudice before I could look at prehistoric American art objectively. How could it take so long to get there? Because really the brainwashing was so profound – if you walked down the street and asked anybody about prehistoric American art, they wouldn’t know anything.

But how can you be sure that your collection of prehistoric American art is authentic?

First of all, I buy fakes, I’ve bought fakes, and I’m sure I will buy more fakes. It’s part of the risk if you collect in almost any field, new or ancient. Mostly it happens when you haven’t done your homework. You have to be smart. I have experts in any field I’m going into. That’s crucial, because then you save lots of time and money. And, luckily, there’s always the opportunity of using special tests. X-rays let you see everything, including evidence of earlier restorations.

But mostly I trust my eye. Looking very hard and seeing if this is fake or not fake. One of the biggest reasons for buying fakes is ego. Like, oh my God, I can own a great masterpiece. Fakers know what you want, and they know how to suck you in. You have to be very objective with yourself. So much of it is first impression. It’s unbelievable how the first impression really works. If you have any doubts, any doubt when you first see it, turn the page. Don’t even go back. It’s a waste of time.

But I suppose you’ve sometimes gone back after all….

Absolutely. Especially in the field I’m dealing with, which is ancient art. You can’t deal in a field where things cost thousands of dollars and be absolutely certain. With stone you can’t be certain, with clay – more so, because you can actually test it.

It’s one thing for you as a collector to buy a fake, but selling a fake as a dealer is another thing.

You have to stop dealing. That’s what you have to do. There are certain fields, like with Chinese stone, where you can’t even begin to deal. I’ve seen factories in China where they make these fakes, and there are lots of brilliant things, thousands of pieces. But if you’re collecting these things, it’s better to assume they’re fakes than to assume they’re real. So, if I’m looking at something, the first step is to assume everything is a fake. That’s just years of experience talking. I get offered things all the time. Some of the people I know, others I don’t know. Even minerals in their natural form can be faked. Whatever is valued can be faked. And now, with very good copy techniques, it becomes more and more difficult and risky. But I will often take the risk.

Why?

Because I will really trust my judgment and say, OK, I think this is real. It just looks right to me. And you have to trust yourself. I hope some day I’ll be able to test stone. Stone is a big issue. There’s still no way to really test the age of stone. You just have to look at it very closely with your own eye. Look, look, look. It’s a total risk. I know I’m doing it, I know it’s a risk, but if it turns out to be real, it’s a nice addition. There’s no another way. And I’m sure all great collectors have bought fakes.

There are also many fakes in museum collections.

Oh, yes. I wish I could be a dealer of Old Master paintings, but it’s just too much to know. At that level, fakes and copies…it’s very serious.

Do you mean to say that in this niche even your own trained eye would be unable to distinguish an original from a fake?

No, my eyes are not trained for Old Masters. I love them, but I think that’s a field that can take a lifetime to learn. It’s too late for me.

Is that the most difficult field in the art world to deal with?

Yes, for me it would be the most difficult. Because there are so many good artists you’ve never heard about but which you have to put in context. It takes years and years of looking. I mean, just seeing all of the 16th- and 17th-century artists in Rome alone…. It would be really fun. And that’s why I admire this field. I think the people must take a lot of risks.

How did you train your eye as a dealer?

Look, look, look, look…. Looking all the time. Only looking. Don’t read too much. Basically, the looking teaches you. It happens in different ways. When I was a photography dealer in the 1970s and 1980s, I went to a lot of auctions, because the history of photography was being rewritten then. Things nobody had even seen before came out, and the whole photo community was running to auctions. It was the way you learned – just going and looking at what was coming out. Now it’s all on the Internet, so it’s even easier because you can look all day long.

And basically there’s no more need to physically attend auctions?

No. In fact, I quite often get commissions to bid, but I’m not in the rooms. I refuse to be in a room during the auction because I need to focus without other people around me and without my ego playing into it.

Physical presence stimulates the ego?

Yes, because there are thoughts like “I can spend more money than him” and so on. As an absentee bidder, it’s much easier to focus. I can’t bid in rooms anymore.

But you used to?

Oh, I did for decades. It’s in my blood. I come from a family of Jewish depression-era rag-pickers. Somebody else’s garbage is my treasure. I think it’s very genetic. I hope it is. Why not?

All auctions are now online, brought together in different portals. There are five, six or seven of them. This is the best place to buy art, because the whole world is there. It’s a giant international flea market. It takes so much less time to find something to buy nowadays. It’s so efficient. It’s a blessing for collectors.

So, in essence, what you do on a day-to-day basis is dig through a huge pile of junk?

Oh, yes! Endless amounts. It’s like panning for gold. You get better at it, but you also make giant mistakes. For example, I’m a big fan of Bansky. He was in New York, and as I walked through a park one day, I noticed a group of paintings that someone had signed as Bansky. I got very angry, because I really respect him and was upset that someone would fake them and capitalise on his fame. Three months later, I woke up in the middle of the night and ran to my computer in shock – it turned out that Bansky had made all of those paintings! They were originals. And there I was, at the height of my career, completely fooled. I remind myself of that quite often, of how stupid I am. Things you have sold, things you haven’t bought, etc. It’s an opportunity to understand that you’re only human, that you can make a lot of mistakes.

And you’re able to laugh about it?

Of course I laugh, because I know what an idiot I am. Sometimes you can be really, really smart and get things completely right long before anyone else does, or you can completely miss the mark. You know, Sugimoto came into my gallery and showed me his photographs. And I didn’t want to show him. Another photographer I did the same thing to was Sally Mann. I didn’t really have a great eye for contemporary photography. It wasn’t the field I was focused on. And the art world was very divided back then. Minimalism, colour field, conceptual, postmodernism – everyone was in a camp, like in a big board game. That doesn’t exist anymore. A big transformation has happened; everything is the same as long as it’s good on a big white wall.

For many years you kept your collections away from the public. A while ago it was reported in the media that you’re preparing to open an art space in a former Yonkers jail on the outskirts of New York City. Why?

Yes, this is a big change in my life. Everything that I collected for forty years will now be accessible to me…I’ll be able to see what I’ve collected. It’s usually been in storage, and now it will be in “open storage”.

But why did you decide to do it?

I just said, I’ve been doing this for forty years and I would love to see what I have.

So, you’re doing it for yourself?

Yes, it was that simple. I would like to just look at it all and enjoy it.

But maybe the space will be too small. Have you calculated whether there will be room for all 15 of your collections?

There should be enough. And I also get rid of some things from time to time. I expect that one day Chinese ceramics will sell and pre-Columbian art will sell. When the time comes.

As a dealer, is it easy for you to say goodbye to works of art in your own collection?

Sure. But it’s not a problem with most things. Usually the things that go into a collection are meant to stay as a collection. And then there comes a time to move on. That’s the cycle. Usually when you finish your own circle of learning about it, you’ve completely understood something and it’s become a part of you – then you can let it go. I don’t think of the things in my collection as of things that I own. No. I don’t think about owning these pieces. I think about having them for a period to learn from, and then moving on. Owning is not the goal. Learning is.

And, when you do let them go, is it important to you where they end up?

Yes, it is important to me where they go and also that people will be able to see them. I can’t imagine not collecting. I can’t imagine not being interested in things. It’s just a luxury like opera. The first time I saw art in a museum, it was like wow, and you can own it? You know, it was really that simple. The art world is a really great environment, because everybody has a life in there. You’ve also found a life, just writing about nuts like me!

Undeniably. Sometimes I feel like I’ve become a kind of collector myself. I collect conversations.

Of course, you are.

Do you still remember all the things you have in your many collections?

No. It will be interesting when I get everything into the jail. Then there will be many moments to remember. There are also lots of collections within a collection. When buying larger groups, I often say to myself, “Would this make an interesting book?” I recently bought a collection of 60 glass negatives of Ellis Island, and it’s sort of nostalgic, and a link to my past, because that’s how my family came to America. It could be my grandfather there.

How do you manage all your collections? Do you have a curator?

We are very organised. Everything is digitalised and accessible. To accomplish this takes three staff: information management, logistics and accounting.

Does a time ever come when you can say a collection is complete?

Yes. In my way of collecting, a collection must have and must accomplish a lot of things before it’s complete. It has to have breadth and depth and it must have masterpieces. And then, when you can’t add to it anymore because no piece will be better than the last piece, then it’s finished. But I keep adding to some collections even when they’re finished. “More is more” is a notion I’m very comfortable with. Like my mineral collection, I measure it in tons.

What’s so special about quartz?

Nature is the greatest artist. The greatest art experience in the world is the Tucson mineral fair in Arizona every February. It takes over the whole city, miles and miles of minerals. People from all over the world come and buy minerals. It’s incredibly exciting, because you see so much.

Are there differences in the process of choosing art and crystals?

It’s the same. It’s based on aesthetics. Just look at it. Art has its own narrative and so do minerals. Sometimes there might be five or six different chapters of geological history in one piece. I especially like “plates”. They’re amazingly beautiful.

But you don’t buy crystals on the Internet, do you?

Almost always, especially from China. There are great dealers in China, India and Russia.

Don’t you need light to evaluate them?

No, you just need a photograph.

What do you think is the responsibility of a collector, if any?

None. I respect everyone’s own agenda. I never spend other people’s money. They can do what they want. I think the only responsibility – let’s not call it a responsibility, it’s a preference – is to not bury it, but to share. Let people see what you have, give people access to it. That doesn’t mean opening up your life to them, but if you have things that add to the history of art, they should not be kept secret. People should know about them. People should see them. That is the only thing.

Will the former jail be open to the public?

Not to the general public, only to professionals, museum directors, curators, collectors etc. I want the public to see that material, but that is another business altogether and I leave that to the museums, where I hope my collections will eventually reside.

Why don’t you want to open it to the general public, like a museum?

I’m not interested in spending my time teaching. I’m interested in spending my time collecting. I’m addicted.

There is no cure?

Of course, there is a cure: no more money. But as long as you can be in it, it’s a field filled with fun and with so many opportunities. It’s more fun finding something to add to your collection than it is buying shares in IBM. It’s the same activity, but with no downside. It keeps the mind active, and you end up with something beautiful. And it offers an inner dialogue. When you collect, it’s ongoing – why did I do this or that, how did I make this or that, why has this language stayed this way, and so on…. Besides, all collections are in large part connected with each other.

If your collections eventually end up in a museum, will it be important to you that your name is connected to them?

Why not? I have an ego, but it won’t be a deal breaker. But in one way it would really help. I would love to build a brand and reputation as a great collector, because it helps in building a good provenance. Professionally, and considering the reality of things and the shape of power in this world, it would be great to have a name that’s recognised. I would love it if all that were needed for a piece or collection to have gravitas is “Provenance: Daniel Wolf”.

By Una Meistere, Arterritory.com

Una Meistere is editor of the magazine ‘Arterritory Conversations with Collectors’ and director of the art and culture website Arterritory, which focuses on Baltic, Scandinavian, and Russian art.