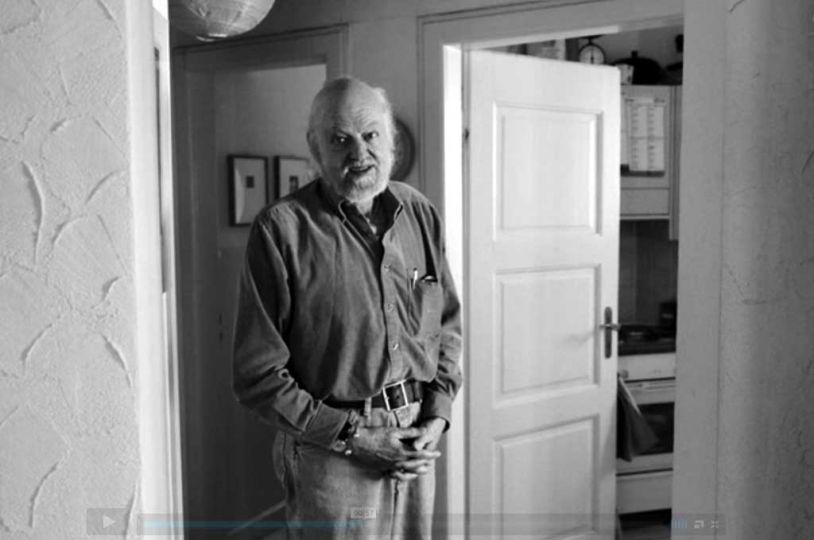

Allan Porter’s smile puts you immediately at ease. His wise face is a sign of all that he remembers. We see upon it his love for life, which he has long expressed through photography. In his apartment in Lucerne, Switzerland, Porter wore a white beard, pants with the cuffs rolled up, and a thin ponytail. We shared a hearty meal of wine, rillettes and cheese brought by his old friend—and peerless procurer—Jean-Jacques Naudet. It was a lunch between adopted sons, one from Europe, the other from America, two continents with opposing cultures but an eternal love for each other.

The editor of the magazine Camera from 1965 to 1981, Allan Porter, now 80, remains one of the most important links between photography and the public. Hidden away since the 1960s in this small Swiss-German town, it’s almost as if he’s been forgotten; some people assumed that he had passed away. However, under his direction, Camera, a major publication in the photo world since its inception in 1922, experienced an unprecedented success.

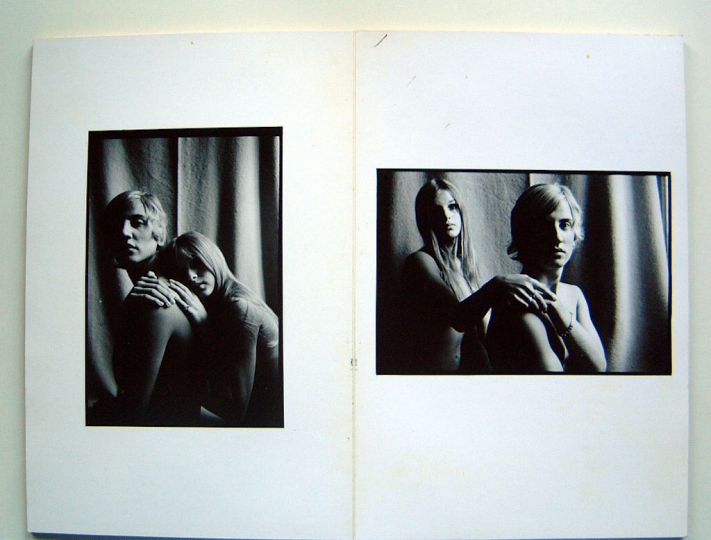

The review witnessed the golden age of documentary, the advent of color, the experiments in abstraction and minimalism, as photography began its shift towards acceptance in the art world. Important figures like Josef Koudelka, Ralph Gibson, Duane Michals, Sarah Moon, Eikoh Hosoe, Bernard Plossu, David Goldblatt and Leslie Krims published their photographs in Camera, where they were recognized not as a mere illustration, but as works of art in themselves.

“All those photographers remember me,” says Porter, “but they never mention my name. Instead they talk about the genesis of their work, their rise to fame, always in the first-person. It’s like the relationship between a psychoanalyst and a patient. Editors like me know too much about them. They want to forget about their father figures.”

In addition to championing the work of modern photographers during his tenure at Camera, Porter revisited neglected periods of the past: Alfred Stieglitz and his magazine Camera Work (Camera, Dec. 1969), early photojournalism (Oct. 1976), pictorialism (Dec. 1970) and 19th century American photography (Dec. 1976). In December 1972, for Camera’s fiftieth anniversary, a special edition dedicated to the history of the medium was published, with each issue exploring the work of a different photographer: Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, William Henry Fox Talbot, David Octavius Hill, Lewis W. Hine and Anne W. Brigman up to contemporary photographers like Robert Frank, Richard Avedon and Diane Arbus.

“My idea was to embrace what has been forgotten by historians,” says Porter. “A number of photographers have been underappreciated, like Josef Sudek. At the time, many people came together to help me approach pre-War French and German photography, including Photokina co-founder Fritz Gruber, the collector André Jammes, the photographer Marc Riboud, and of course the historian Beaumont Newhall, whose knowledge has always impressed me.”

Porter has made many friends through photography: Franck Zachary, his mentor at Holiday – a travel magazine that is forgotten today but counted among its contributors Truman Capote or Bruce Davidson – and some other relatives like Marvel Israel and Alexey Brodovitch. “These three taught me everything,” says Porter. “At the time, even the writers respected artistic directors. It was a profession that carried weight. When I joined Holiday as an editor, it was the first time I was free.” An amateur photographer, Porter took portraits of Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston and Bill Brandt. In 1973, Porter was visited at his Camera offices by Henri Cartier-Bresson, who had been upset following the departure of the previous editor-in-chief, Romeo Martinez. But their differences were no match for their shared passion for photography, and they went on to form a lasting friendship.

“To speak of Allan Porter is to speak of the evolution of contemporary photography over the past fifty years, to which Allan made crucial contributions,” says photographer Ralph Gibson. “When he started editing Camera, a new generation of photographers was emerging, and Allan was the first to realize it. He had understood that with the Second World War, Europe had lost the equivalent of an entire generation of development in photography. After the masters of the 1920s, ‘30s and ‘40s, it wasn’t until the mid-1970s that European photography saw a revival.”

Allan Porter has always been a prolific champion of photography, but a quiet one. Perhaps it’s more suitable to remember his initiatives. All that he has written about photography, of course. All that he has said about photography while sitting around a table, even better.