Art historian Maeva Dubrez has published a well-documented essay on Deborah Turbeville’s work, the fruit of extensive research, with ACTEDITIONS. Here is an extract of her essay:

This essay solves the enigma of Deborah Turbeville’s work by going over her photographic prints with a fine tooth-comb and exposing the infinite layers that lie beneath. She is more than a photographer : her work continually breaks down the blurred boundaries between photography and cinema, forever exploring new horizons. This decision to produce a study that breaks away from the usual academic form is deliberate. I’ve opted for narrative writing, going through a back door, in order to unveil a hidden dimension of her work. This mirrors the way Turbeville herself deftly navigated the open boundaries between reality and fiction in her photographic universe. I use facts and tangible elements drawn from her approach, while undertaking an eclectic analysis that encompasses theoretical, philosophical, historical, hypothetical, and interpretive perspectives.

From her earliest years as a photographer, Deborah Turbeville had always proven herself to be an authentic artist, charting her own course with uncompromising commitment. She created an entirely autonomous photographic world imbued with a temporality intrinsic to her personality. This universe held immeasurable value to her, an essence firmly rooted in her being, that formed the very foundation of her vision, one that would unquestionably influence the course of fashion photography.

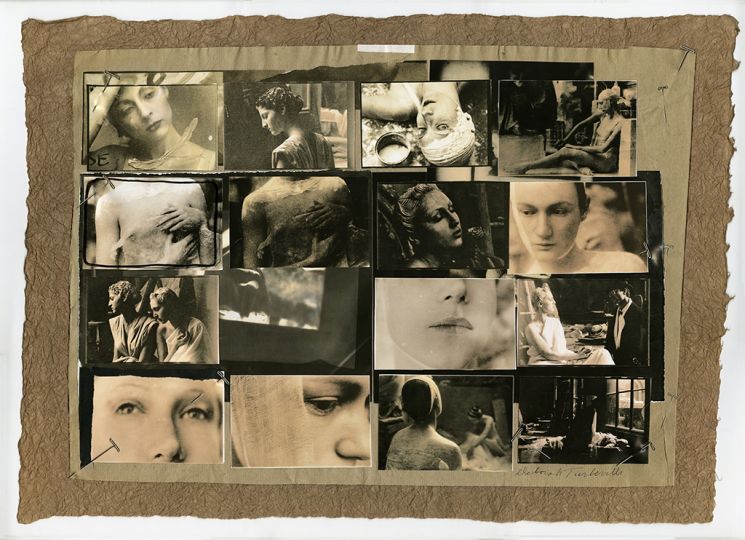

Deborah Turbeville always refuted the reductive label of “fashion photographer.”[1] She couldn’t bear to be confined to a specific category, preferring to leave her photographs to blossom freely. And yet, she readily acknowledged that her collaborations with the fashion world were fundamental elements in the construction of her photographic series.[2] The way she structured her photo shoots can be compared to that of a “small film production company,”[3] a description that she herself recorded in her notes. She shot images that came to life through the lens of her camera. Through her vision, the creative brief was transformed into a real shoot, where make-up artists, actresses, sets, and costumes were sine qua non for the creation of her personal photographic series. When she planned a shoot, she envisioned it as an integral part of her oeuvre. Without this photo shoot for the editorial “Il bianco e blu di maglia mole” in the March 1977 issue of Vogue Italia in March 1977, her enigmatic series L’Heure entre chien et loup would never have seen the light of day.

I have deliberately chosen one plate from the Vogue magazine editorial to compare it with the prints from her series. The images were shot at the same moment, from the same angle. However, despite this simultaneity, the photographs in the series have undergone a strange metamorphosis. They have become petrified in another space-time, where the “actresses” are nothing more than ghostly figures drifting in a parallel reality that only Turbeville can capture. It’s almost as if she had fitted her camera with a magic filter that distorted while recording. I was enthralled by this finding. Her approach is remarkably atypical: her primary inspiration was film, and she was forever trying to create her own universe, a world out of time. And now, I see ghosts in her photographs. As I plunge deeper into her personal oeuvre, Deborah Turbeville’s eerie aura seems to creep into each of her photographs, transforming them into riddles to be solved: where does this timeless world inhabited by ghosts arise from? Why do these apparitions continue to haunt her photographs? While browsing through her notebooks, which have been carefully archived by MUUS Collection, I read one of her notes that she wanted to include in her artist biography and which supports this observation: “Often described as mystical, Turbeville remains an enigma both for herself and as an artist.”[4]

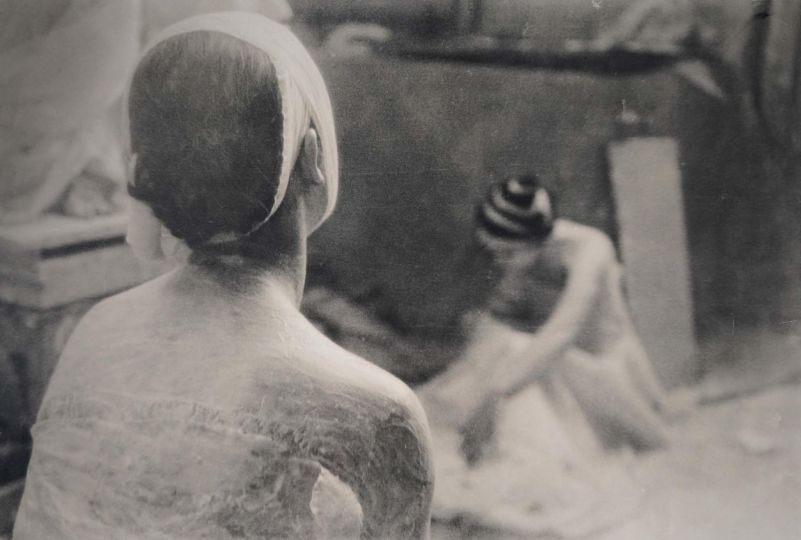

For some, understanding the processes behind the prints Turbeville created remains shrouded in mystery, just like her infinitely varied experiments in photographic processing. Before looking into her archives, I was convinced that she over-exposed her photographs during the shooting, which is what is frequently described in the texts exploring her work. However, what I found in the archives of MUUS Collection indicated that this question deserves further consideration. Once I was in the archives, I immediately began to examine the negatives she used for “Il bianco e blu di maglia mode” (Vogue Italia, 1977). To my surprise, the negatives from the series L’Heure entre chien et loup (shot for Vogue Italia) do not reveal any significant overexposure or underexposure, while the subjects captured are undeniably sharp — at least much sharper than in her personal series. I was especially interested in the series of color slides featuring Isabelle Weingarten and Ella Milewicz transfixed in a ghostly atmosphere. Turbeville had photographed them in that pose no fewer than fifteen times, but I found no trace of the slide used for her personal series. Moreover, the slides were in color, while the photographs in her personal series were black and white, which was problematic. I kept looking, but the negative was nowhere to be found.

Browsing through the storage boxes that contained her precious personal prints, a revelation emerged: her series L’heure entre chien et loup was shot largely with a Polaroid camera. This revelation lifted the veil as to why certain images did not turn up among the negatives photographed with her Nikon. At the time, owing to their capacity to instantly develop images into positives, Polaroid cameras were essentially used as a tool for testing lighting. The type of camera used by Turbeville – a Polaroid Land Camera 190 – was equipped with a telemetric viewfinder that allowed the diaphragm and shutter speed to be adjusted.[5] Everything suggests that, although Deborah Turbeville was given considerable freedom with her commissions, her editors insisted that readers be shown a glimpse of the clothing collections presented, particularly in a magazine like Vogue. But despite such strictures, the photographer had a parallel vision on what she wanted to capture to fuel her own oeuvre.

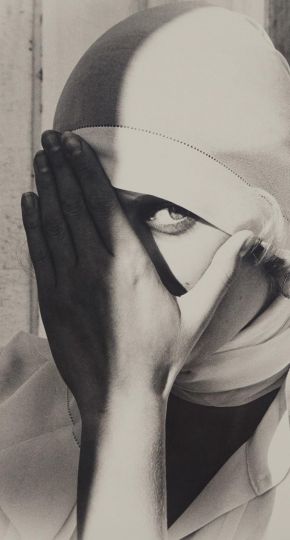

The use of Polaroids might explain this “filter” that I had imagined placed in front of her Nikon camera. But this is not the only element at play; Turbeville also regularly resorted to another type of filter. At the time Deborah Turbeville did the shoot “Il bianco e blu di maglia mole” for Vogue Italia, Bertrand Cardon had not yet begun working for her. But during our conversation, Cardon told me that in 1985, during an assignment for Vogue US, she specifically asked for a 60×80 glass plate and “dulling spray,” which she mixed with water before applying to the glass. Then she started photographing through the plate. Dulling spray is commonly used in the film industry to control the reflection of light from various surfaces, helping create the intended mood while removing visual distractions during the shoot. Turbeville explained to Bertrand that this method was something she had mastered on photo shoots in the United States. A close analysis of three specific Polaroids suggests that she probably used this glass plate as a diffuser in front of her Polaroid lens, thus creating a fog-like effect to blur elements of the image and build up an even more ghostly atmosphere. Cardon also told me that Turbeville’s overexposure in her photographs was not intentional, but the result of accidents caused by sudden shifts from low to bright light. He recounted that she didn’t know how to set the shutter speed or aperture, which in turn caused errors, and accidents that she described as “beautiful.”[6] After developing her films, she would systematically save the overexposed images for her personal work.

Her penchant for errors or “erratas” was not restricted to photographing. She closely collaborated with her printer and assistant in New York, Dawn Close, whose role was pivotal in creating her ghostly atmospheres. Close would print several versions of the same image with different alterations. As I explored Turbeville’s archives, I realized that she never stopped working on her photographs, as though each print had been left in the developing bath, never quite finished. She reproduced some of her images seemingly ad infinitum. Each time I opened a new box, I would discover the same subject, albeit in a different format, on another kind of paper or photographic process, which was sometimes torn, scratched, or marked to the point of near destruction. Some of the Polaroids and other prints in the L’heure entre chien et loup series bore traces of brushes or fingerprints, chemical additions, sepia tones, endless experimentation with different processes, and even internegatives. In addition, the gelatin-silver prints in this series were in some cases derived from internegatives of her Polaroid prints. It was almost vertiginous. Her experimental photographic process was endless, just like the stories she tells, which are always left open-ended.

According to Bertrand, who sometimes watched the prints being developed in the laboratory, it appears that Turbeville would ask “her printer”, Dawn Close, to apply overexposure effects to a negative that had initially been correctly exposed. Then, Close would use a prolonged exposure time to selectively work on the highlights, while adjusting the contrast of the print using variable-grade papers. The act of exposing light-sensitive paper in the laboratory thus bears similarities to exposing photographic film during the shooting process.

Walter Benjamin previously studied this technique when he examined an 1845 cemetery photograph by D.O. Hill and R. Adamson. In the mid-19th century, the use of photographic plates required a long exposure, meaning that the photograph recorded an extended period during which the space being photographed had time to change, thus altering the image. Benjamin refers to the blurred appearances revealed through this process, noting that “in the old images everything was made to last.”[7] In the early 20th century, Emil Orlik, a Berlin graphic artist, coined the expression “luminous accumulation.”[8] This accumulation of light, evident in Turbeville’s prints, leaves a nebulous veil that transforms her white garment-clad actresses into ghostly apparitions.

Photographic errors are integral to Turbeville’s oeuvre. As I looked through the archive, this aspect called to mind Fautographie, Petite histoire de l’erreur photographique, by Clément Chéroux, who writes: “Some authors are haunted by erratum. Jorge Luis Borges, whose taste for literary facetiousness is legendary, was not bothered by typographical, transcription, or translation errors; on the contrary, he believed that errata would enrich his books.”[9] For Turbeville, the naturally occurring errata is precisely what gives the work its potency, forever captivating and haunting us.

Regardless of whether one agrees with Jacques Derrida’s theories in general, in Ghost Dance, the philosopher offers an observation that seems particularly apropos for Turbeville’s work, pointing out that “cinema [and photography since its origin], is an art of “fantomachie.”[10] According to Derrida, the ghost is a fantastical being, but also a fantasized, phantasmatic being. It manifests an imaginary, something personal, both feared and desired. This haunting image, which we might call “ectoplasm” or “spectrality,” is “haunted by the void, by death,” according to Jean Baudrillard,[11] another philosopher whose ideas seem especially relevant in the context of Turbeville’s work. Derrida also uses the term “spectrality,” which he later retitles “hauntology,” to expand its meaning as “the logic of haunting.”[12] This logic is akin to the perpetual return of a dead person, a ghost. Since their origins, cinema and photography have skillfully played with these “spectralities,” which still haunt and manipulate our imaginations to this day. While Turbeville never explicitly refers to ghosts, her works depict silhouettes, shadows, and ancient faces “that appear…trapped in time, raising questions about other realities.”[13] In Past Imperfect, she evokes beings from “another world into which we were not invited to enter. All those faces haunted me… I wanted to photograph them… They seemed to have been resurrected, gathered (captured in Paris) by the fashion world… and were now parading before me.”[14] Thus, through the words of Derrida, the philosophy of Baudrillard, or the universe of Turbeville, photography emerges as a space where the frontiers between tangible and intangible fade away. It’s a space where past and present interact, where the ghosts of memory come to life to haunt us, and where fashion itself seems to morph into a specter.

In this regard, Deborah Turbeville embraces the photographic approach, not so much as part of the fashion industry, but rather as an expression of theories of the image, such as those proposed by Philippe Dubois[15] and Siegfried Kracauer.[16]. Both men attribute to photography a capacity to record “an out-of-time death” and to offer “a world displaced from reality…a world of the dead, in its independence from humans.”[17] By photographing a subject, the snapshot freezes the living, condemning it to an immutable form. The subject dies precisely when the photograph is taken, yet its image remains, preserved in a space-time detached from the reality of the living. The otherworldly ambiance of Deborah Turbeville’s photographs becomes an act of execution designed to keep these fashionable forms in frozen time. It remains to uncover the mystery underlying this enigmatic approach and to discover the aim that drove it.

Maeva Dubrez – Hidden Under Layers

November 2023, publié par ACTEDITIONS

84 pages. 300 x 450 mm

Français et anglais, traduction de Paula Cook

Disponible dans les bonnes librairies et en ligne.

Notes blibliographiques

- Patrick Roegiers (5 August 1986), The ambiguous charm of Deborah Turbeville, Le Monde, p. 13 “I almost exclusively work on commission (…) The images taken in the École des Beaux-Arts [in Paris], where young women pose with bandages, were commissioned by Vogue France for beauty products. The idea would never have occurred to me otherwise.” Commercial work is my real creation.

- Patrick Roegiers (5 August 1986), The ambiguous charm of Deborah Turbeville, Le Monde, p. 13

- DT Loose pages – Biography Notes, MUUS Collection

- Loose pages – Biography Notes, MUUS Collection “often described as mystic, Turbeville remains an enigma both in herself and as an artist”

- Information obtained during a discussion with Bertrand Cardon, former assistant of Deborah Turbeville

- Loose pages – Biography Notes, MUUS Collection

- Walter Benjamin, Petite histoire de la photograhie, Paris, Société Française de Photographie, 1996, p.14.15

- Emil Orlik, Uber Photographie Kleine, Aufstaze, Berlin, Propylaën, 1924, p.32-34

- Clément Chéroux, Fautographie, Petite histoire de l’erreur photographique, Crisnée, Editions Yellow Now, 2003, p.14

- “Cinema is the art of ghosts, a battle of phantoms (…) That’s what I think the cinema’s about, when it’s not boring. It’s the art of allowing ghosts to come back (…) so ghosts do exist… and it’s the ghosts who will answer you. Perhaps they already have…”, in Ghost Dance, 1983, Ken McMullen, 16’46 min.

- Jean Baudrillard, Marc Guillaume, Figures de l’altérité, Descartes et cie, 1994, p. 37.

- Jacques Derrida, Spectres de Marx, Galilée, 1993, p. 31

- Deborah Turbeville, Past Imperfect, Göttingen, Steild, 2009

- Ibid.

- Philippe Dubois, L’acte photographique, Paris, Nathan, 1900, p.160

- Sigfried Kracauer, L’ornement de la masse, Paris, La Découverte, 2008 (1963), p. 47

- Ibid