A Conversation with A Yin (Traveling a Distant Journey)

By: CYJO

Mongolia, the “Nation on the Back of Horses”, was once the largest contiguous land empire in the world’s history. Many have made movies and written publications illustrating Genghis Khan’s glorious Mongol Empire in the 13th century. But who are documenting the people, their dissipating traditions and the fast changing terrain today?

A Yin, a self-taught, award winning photographer, born 1970 and raised in Xing’an Meng on the fringe of Keer Qing grassland has devoted his life passionately recording the Mongolian culture. He has windblown, tussled hair and only wears various shades of nature green (down to his socks), symbolizing the lush grasslands that once carpeted the country. And his slightly weathered skin is a proud marking of working through extreme weather conditions including intense sandstorms and winter blizzards as he followed herders and captured their everyday lives for the past years.

Since the 1980’s, he has been writing about and photographing Mongolian culture with over 200,000 negatives of history under his belt. His first major photographic book, “Followers of Genghis Khan, Nomadic Mongolians of China” encapsulates the people and their culture as part of his mission to preserve the disappearing nomadic culture through his immersive photographs. And his second major photographic book, “Schools” illustrates the Mongolian school system in the 1990’s and the dramatic changes the people have undergone within a very short time frame.

A Yin reveals the lives of select Mongolians both photographically and textually, where one can’t help but feel privileged to view such authentic, sublime beauty created by an individual who has studied and lived within the culture for so many years. As August Sanders’ extensive work portrayed the social stratum of industrialized Germany, A Yin’s work captures society and its relationship to a modernizing Mongolia.

CYJO: Can you describe your childhood? Has it influenced the work you have produced about the Mongolian culture?

A Yin: I was born in a very poor family where my parents were farmers. My hometown was a small village in eastern Mongolia. The nomadic life there vanished 200 years ago and many in the community worked in the fields. I was reading and writing at an early age but had to drop out of school when I was 14 years old because we couldn’t afford it anymore. Many kids were dropping out of school due to the growing poverty.

My photography is closely related to my childhood. Many subjects that I have photographed have come from a similar background because that is what I can relate to and what I find interesting.

CYJO: How did you become a photographer?

A Yin: I actually had a very strong dream of wanting to get involved in art since I was young. When I was in elementary school, I learned Chinese calligraphy and painting and liked it a lot.

After I dropped out of school, I worked in the fields and herded the sheep. My mother passed away when I was 16 years old, so I needed to find more substantial work to survive and support my family. I traded garments in towns and villages. And in 1987, I started working in local newspapers, writing various reports using the inner Mongolian language. From there, I gradually began taking pictures for Mongolian newspapers and magazines.

At the end of 1989, I found 2 opportunities to take pictures. I learned that many locals in rural areas considered color pictures a novelty, and many wanted to have their pictures taken in color. I also realized that it was rare to have a photojournalist working for a Mongolian newspaper in the rural areas because many individuals in those areas didn’t have the technical knowledge to use the camera. And so I started taking portraits of rural Mongolians who wanted their color photograph and also began shooting for the Xing’An Daily Newspaper. My first camera I used was a simple, Chinese, “Great Wall” camera.

In the early 1990’s, I found myself biking to many villages, where I soon became “the” portrait photographer in that area. People were interested in having their family pictures taken, especially when there was a newborn. During that time, I often used a Chinese, automatic film camera, a “Sea-Gull” 4A.

CYJO: What made you decide to focus solely on Mongolia? Have you thought about creating other bodies of work on different cultures?

A Yin: I never studied photography. When I had my first camera, I wanted to record the social life of the area including the poor. I felt connected to the people and wanted to make pictures for them. I never initially thought of developing a series. The series evolved organically. My mission and passion is to continue to record the Mongolian culture for the rest of my life.

CYJO: How did the series published in “The Followers of Genghis Khan” evolve?

A Yin: Between 1990-1996, I photographed all different types of topics in Inner Mongolia. And in 1992, I attended Inner Mongolia University to study Mongolian culture and history where I was able to obtain a deeper understanding of it. In 1996, I realized that the existing culture was going to disappear, and that it was very important to capture it.

In 1998, I had moved with my family to East Ujimqin Qi (also known as East Qi) in Inner Mongolia’s Xilin Gol grassland to document the dissipating tradition since many who lived there still retained their Mongolian traditions. From there, the idea of creating a portrait series emerged.

After settling in the grasslands, I created and ran a magazine, “WuJu Muqi Culture”. Because I didn’t know the tradition and culture in that area, it was important to learn it before taking their photographs. During the next 5 years, I wrote 18 books and edited 10 books about the culture. In 1999, I also had a photo studio taking general ID photos, which helped me make a living. I started taking professional portraits of the people for the series in 2003.

CYJO: Can you describe one of your most moving photographs?

A Yin: One of my most moving photographs was of a man holding his goat, who was protecting it in a sandstorm. Up to 2 kilos of sand can collect in the fur of a goat during a storm.

This picture really depressed me because it captured the harmful environmental changes that were happening which were drastically changing people’s lives. Their environments were once beautiful grasslands, and now it was dirt and sand. I started seeing these changes since 1998, and it got significantly worse since 2000 with sandstorms becoming more frequent every year.

There have been many changes in the culture with the environmental changes being the most serious partly due to excessive exploitation of the grasslands and mining excavation projects. But there are many other types of changes. People who once rode horses are now riding motorbikes. Before, they lived in yurts (traditional housing) made of fabric. That changed to iron yurts, which then changed to brick houses. The ways of living are changing, and the locals have no control of many of the major changes that are happening.

CYJO: How are the people handling the changes?

A Yin: Many people don’t know how to deal with those changes. The older generation prefers to keep the traditional ways, but the younger generation likes to live in the modern way. They are studying mandarin and going into the cities.

CYJO: Can you talk about your most recent book, “Schools”?

A Yin: In “Schools”, I show the development of Inner Mongolia education. The beginning of the book has photos taken during the 90’s of gacha (village) schools. Many schools then were dilapidated old houses. Some classes were held in teachers’ homes, and other students had to carry tables and chairs to have classes in different locations.

In 1998, I focused on “citizen-managed” teachers. Citizen-managed teachers were not included in the state managed faculty and had lower secondary school education or higher. They helped increase the amount of rural, school teachers needed to teach primary schools. Some taught secondary schools. Many citizen-managed teachers had lost their jobs due to a change in education policy. And then in 2006, the government cancelled all the schools in the villages and townships and moved the schools to the cities. The next section documents this.

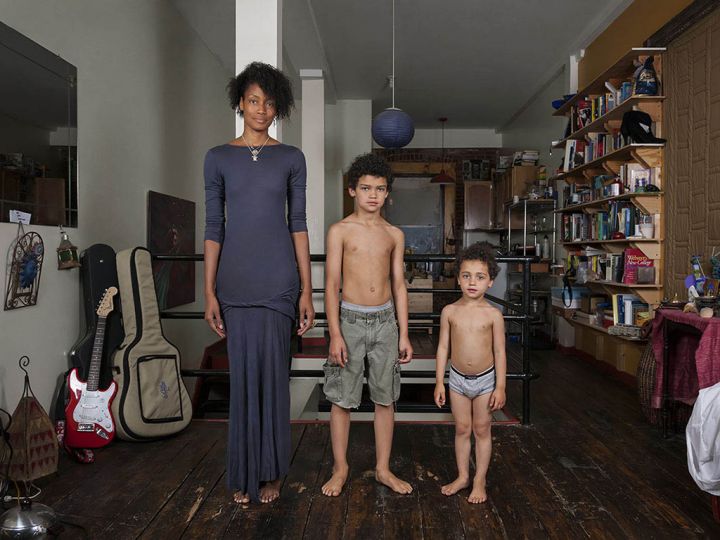

In the final section, “Urban Schools”, I pair black and white portraits I’ve shot of children from 2005-2009 to color portraits taken of them in 2010. From these contrasting portraits, it’s easy to see their rapidly changing lifestyles and the changes of the education system. In some rural areas, the rate of those dropping out of school is increasing because of the long distances students have to travel to go to school and the increasing education fees.

CYJO: What do you have planned for the future?

A Yin: I’m photographing 5 different Mongolian topics and plan to complete them within 3 years. Everything I covered and will continue to cover will always revolve around three major topics – the culture disappearing, environmental change, and the culture and life of the local people.

This interview was edited by CYJO.

M.R. Gallery

No.D06, Mid Second Street 798 Art Zone, No.2 Jiuxianqiao Rd. Chaoyang District, Beijing, China 100015