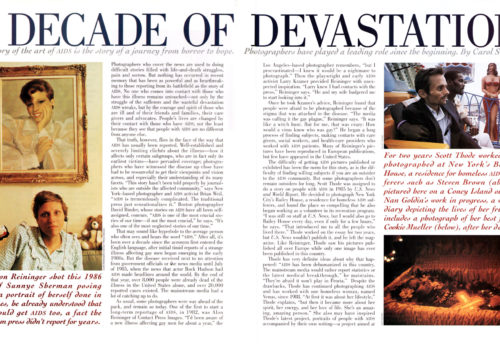

The History of the Art of AIDS is the story of a journey from horror to hope. Photographers have played a leading role since the beginning.

Photographers who cover the news are used to doing difficult stories filled with life-and-death struggles, pain and sorrow. But nothing has occurred in recent memory that has been as powerful and as heartbreaking to those reporting from its battlefield as the story of AIDS. No one who comes into contact with those who have this illness remains untouched-not only by the struggle of the sufferers and the wasteful devastation AIDS wreaks, but by the courage and spirit of those who are ill and of their friends and families, their care givers and advocates. People’s lives are changed by their contact with those who have AIDS, not the least because they see that people with AIDS are no different from anyone else.

That truth, however, flies in the face of the way that AIDS has usually been reported. Well-established and severely limiting clichés about the illness-how it affects only certain subgroups, who are in fact only its earliest victims-have pervaded coverage; photographers who have witnessed the disease up close have had to be resourceful to get their viewpoints and vision across, and especially their understanding of its many facets. “This story hasn’t been told properly by journalists who are outside the affected community,” says New York-based photographer and AIDS activist Brian Weil. “AIDS is tremendously complicated. The traditional press just sensationalizes it.” Boston photographer David Binder, whose stories on AIDS have all been self assigned, concurs. “AIDS is one of the most crucial stories of our time-if not the most crucial,” he says. “It’s also one of the most neglected stories of our time.”

That may sound like hyperbole to the average person who often sees and hears the word “AIDS.” After all, it’s been over a decade since the acronym first entered the English language, after initial timid reports of a strange illness affecting gay men began emerging in the early 1980s. But the disease received next to no attention from government officials or the news media until July of 1985, when the news that actor Rock Hudson had AIDS made headlines around the world. By the end of that year, over 8,000 people were already dead of the illness in the United States alone, and over 20,000 reported cases existed. The mainstream media had a lot of catching up to do.

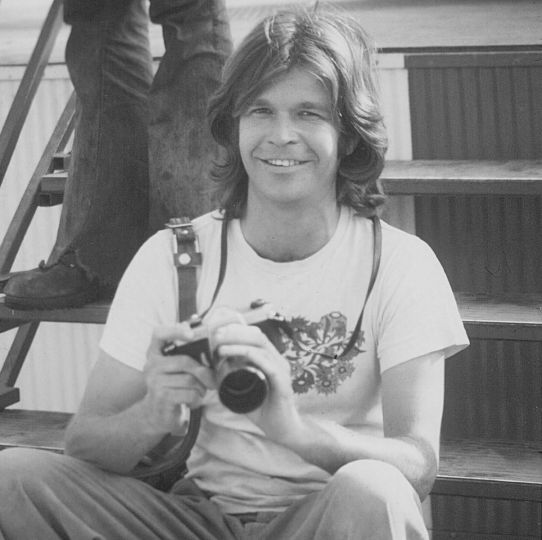

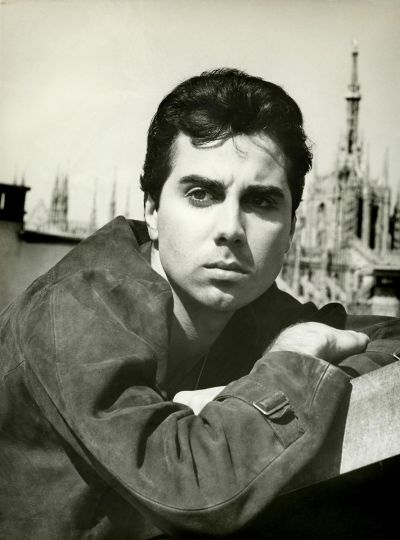

As usual, some photographers were way ahead of the pack, and remain so today. One of the first to start a long-term reportage of AIDS, in 1982, was Alon Reininger of Contact Press Images. “I’d been aware of a new illness affecting gay men for about a year,” the Los Angeles-based photographer remembers, “but I procrastinated-I knew it would be a nightmare to photograph.” Then the playwright and early AIDS activist Larry Kramer provided Reininger with unexpected inspiration. “Larry knew I had contacts with the press,” Reininger says. “He and my wife badgered me to start looking into it.”

Once he took Kramer’s advice, Reininger found that people were afraid to be photographed because of the stigma that was attached to the disease. “The media was calling it the gay plague,” Reininger says. “It was like a witch hunt. But for me, that was crazy: How would a virus know who was gay?” He began a long process of finding subjects, making contacts with care givers, social workers, and health-care providers who worked with AIDS patients. Many of Reininger’s pictures have been reproduced in European publications, but few have appeared in the United States.

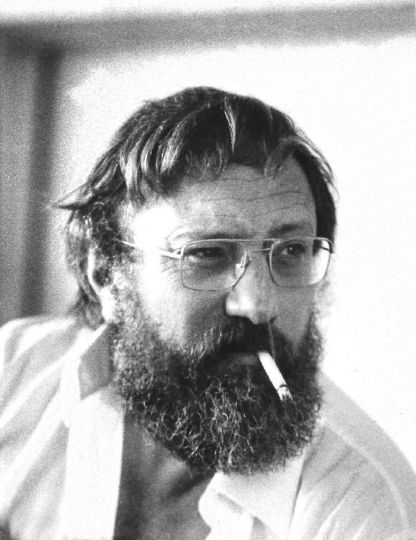

The difficulty of getting AIDS pictures published or exhibited has been the norm for this story, as is the difficulty of finding willing subjects if you are an outsider to the AIDS community. But some photographers don’t remain outsiders for long. Scott Thode was assigned to do a story on people with AIDS in 1985 by U.S. News and World Report. He decided to photograph New York City’s Bailey House, a residence for homeless AIDS sufferers, and found the place so compelling that he also began working as a volunteer in its recreation program. “1 was still on staff at U.S. News, but I would also go to Bailey House every day, even if only for a few hours,” he says. “That introduced me to all the people who lived there.”

Thode worked on the essay for two years, but U.S. News wouldn’t publish it, and he left the magazine. Like Reininger, Thode saw his pictures published all over Europe while only one image has ever been published in this country. Thode has very definite ideas about why that happened: “AIDS has been dehumanized in this country. The mainstream media would rather report statistics or the latest medical breakthrough,” he maintains. “They’re afraid it won’t play in Peoria.” Despite the drawbacks, Thode has continued photographing AIDS and has worked with one homeless woman, named Venus, since 1988. “At first it was about her lifestyle,” Thode explains, “but then it became more about her spirit, her energy, and her love of life. She’s an amazing, amazing person.” She also may have inspired Thode’s latest project, portraits of people with AIDS accompanied by their own writing-a project aimed at conveying their spirit in the face of a life-and-death disease.

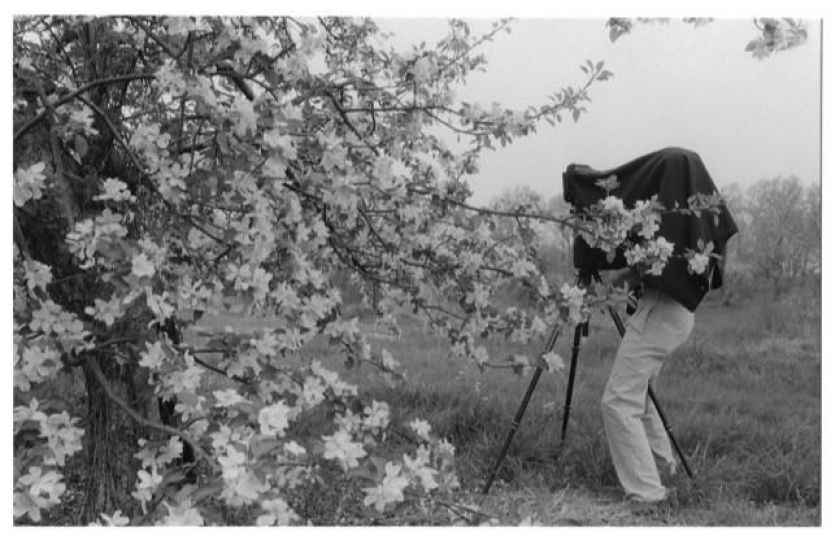

One photographer after another, though, rings variations on Thode’s contention that the media is afraid to dig too deeply into the realities of AIDS. For Nicholas Nixon, who is an artist rather than a photojournalist, the media’s neglect is what made him start an ambitious, and now famous, AIDS project in 1987. “1 had seen a lot of news coverage in which the people just seemed like statistics,” he recounts. “I don’t usually photograph news events, but the force of this just overwhelmed me.”

Nixon and his wife, Bebe, a science writer who worked on the project with him, went through a weekend of “buddy program” training at the AIDS Action Committee in Boston. “They wanted to make sure they could trust us,” he explains. Once they found people who were willing to be photographed, Nixon began making his graphie and controversial-pictures. Using an 8×10 camera and black-and-white film, he produced finely detailed, closeup images of stricken men and women. Some of the images portrayed these people at home with family members; others spelled out the physical devastation of the disease.

When the photographs were first exhibited in 1988 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, AIDS activists staged a protest, and even members of the photography community were taken aback. Not only did the pictures seem to give an unrelentingly bleak view of AIDS, but they were exhibited as art, shorn of any wider context. ln retrospect, Nixon stands by his photographs, although he concedes the validity of some arguments against them, especially those about their essential grimness. “l’rn sympathetic to the position that one should photograph positively,” he says. “I want to give HIV-positive people as much hope as possible too. But the pictures don’t seem exploitative to me.” He also concedes that their exhibition at MOMA was ill advised: “This was always meant to be a book, with text by the people in the pictures, and not just pictures on a wall.” Nixon eventually did publish his book, People With AIDS (David R. Godine), in 1991.

Similar criticisms were leveled at Rosalind Solomon’s unstinting portraits of people with AIDS, which were exhibited at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery in 1988. “People were horrified that I wanted to do this before I even started,” she says. “Some in the photography community were actually belligerent-but my idea was that you should respond to the world.” Much of the negative reaction was aimed at the large size of the prints-about five feet across which made the details of physical deterioration all the more pronounced. “There was a lot of positive response from the people in the pictures and their friends,” she remembers. “Otherwise it was terribly discouraging.” The criticism leveled at Nixon, Solomon, and other photographers arises from a conviction that because AIDS is an extremely sensitive subject, it puts significant burdens on those who want to record it. Showing primarily the physical devastation of AIDS is considered by some to appeal to the fear and prejudice that already hamper understanding. ” I can’t look at a lot of those pictures of AIDS,” Brian Weil maintains. “They’re horrible, and all they do is terrify people.”

Weil is a photographer and artist who became involved with AIDS as a volunteer and activist before he began photographing those affected by it. ln 1985 he helped start a pediatric program for Gay Men’s Health Crisis, one of the first AIDS organizations in the country. “I didn’t get involved in this to take pictures,” he says. “1 took my first picture-of a two-year-old child named Flavia Barcellos who was dying-because her mother asked me to.”

For Weil, making photographs was secondary to the work he was doing as a “buddy” and community organizer. He worked for five years with Flavia’s family; during that time both her mother, Maria, a graduate student, and her father, Fernando, a professor, also died of AIDS, leaving an HIV-negative three-year-old named Adrianna to be brought up by relatives. While photographing the Barcelloses, Weil began to work out his ideas on how he wanted to photograph AIDS. What he wanted to convey was not only its life-and-death drama but also the lesser heroics of daily life, from the tedious hours of medical regimens to the joyful hours of a child’s birthday party. The further Weil got into the subject, the more he realized how complicated AIDS was. “To be a gay man with AIDS in New York is totally different from being a black woman in the Dominican Republic with AIDS,” Weil explains. “The available support services and cultural attitudes are completely different. I want to explain that difference culturally, not physically. l’m not interested in showing the destruction of the body.”

Weil’s exploration of the global impact of AIDS was fueled by his work for the World Health. Organization as a community organizer disseminating information on AIDS and its prevention. He takes his camera on those trips, and since 1988 he has photographed in some seemingly unlikely places, including the go-go bars of Thailand, a country in which AIDS is rampant in the heterosexual population; the gold mines of South Africa, where it is estimated that over 20 percent of the miners are HIV positive; and on the clark streets of the Dominican Republic, where transvestite prostitutes are successfully deployed by the Academy of International Development to provide safe-sex education for clients. ln 1988 Weil also photographed a needle-exchange program for drug addicts in Liverpool, England, that has been overwhelmingly successful at stopping the spread of AIDS, and since then he’s been working with a similar program in New York.

A well-respected artist, Weil has exhibited his large, high-contrast black-and-white photographs and supplementary texts in museums and galleries around the country, and they have also recently been published in book form, Every 17 Seconds: A Global Perspective on the AIDS Crisis (Aperture). “Each time I put up the show it’s a terrible experience,” Weil confesses. “l’ve known and loved all the people in the pictures and most of them have died. But the show is a great educational tool, which is important to me.”

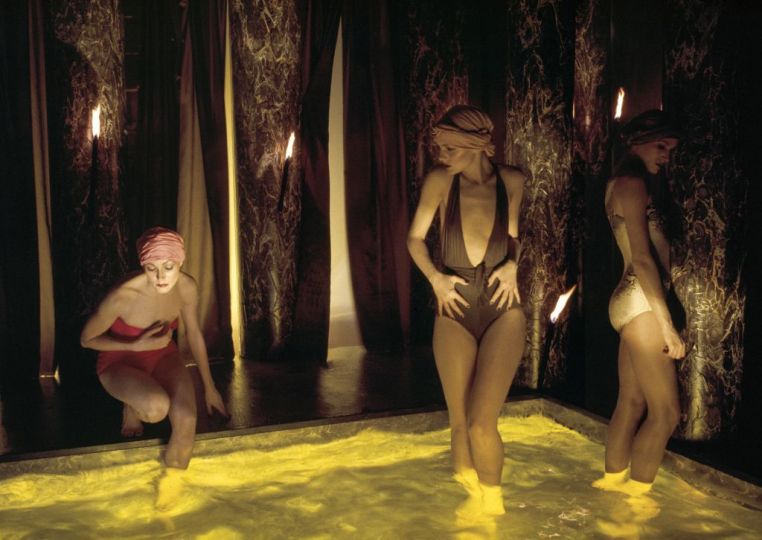

For many photographers, AIDS is something they unwillingly end up photographing in the course of events. For the last 15 years, photographer Nan Goldin’s work has consisted of making images of her friends and family at parties, nightclubs, traveling, or at home. As one by one her friends sickened and died, that process became a part of Goldin’s work. “I had the sense that if I photographed them enough I would never lose them,” she observes. “There’s been a tremendous amount of denial about this illness, though. It wasn’t until a few years ago that I started to feel a real urgency.” One event that spurred her on was the illness and death in 1989 of her best friend, actress and writer Cookie Mueller. She has assembled more than a decade of images of the spirited, exotic-looking Mueller into an extremely moving portfolio that ends with Mueller’s death. “l’ve lost 15 close friends,” Goldin says. “lt’s been completely devastating.”

Like Brian Weil and others, the Berlin-based Goldin is critical of the more mainstream photojournalism and documentary that’s been clone on AIDS. “I don’t like the idea of finding people and photographing their Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions,” she maintains. “That further distances ‘us’ from ‘them,’ as if we’re not all potential AIDS victims. What I want to show is the complexity of the lives that have been lost, so people aren’t just simply statistics.”

Similarly, photographer Bruce Cratsley chose to photograph his own great loss: his lover, who died in 1991. “l’d been photographing David since long before he became sick,” says Cratsley, who is himself HIV positive. “At some point I realized that this was an extraordinary thing that was happening, and that I had an intimate relationship to it. I photographed David just a few hours before he died, not knowing what was about to happen.” Like the rest of Cratsley’s work, his pictures of David Waine have an ethereal, meditative quality to them. “David was very spiritual,” Cratsley explains. “My pictures are a poetic, spiritualized look at AIDS.”

As AIDS makes its way through different groups of the population, photographers are determining to document what happens. Ann Meredith began focusing on women with AIDS in 1987 when she realized how little work had been done on the subject. “The number of women with AIDS more than doubles every six months now,” she points out, “and most people don’t know that.” Like Weil, she shies away from recording the ravages of the illness. lnstead, inspired by one woman who told her, “Hey, we are not dying with this disease, we are living with it,” she shows the daily lives of the women and their loved ones in black-and-white photographs, written commentary, and videotapes. “The goal of my work is to educate, to raise the consciousness of the general public, and to wake people up,” Meredith says.

But convincing people to participate wasn’t easy. “It took months to find people willing to be photographed,” she remembers. “lt was risky for them, and they worried about things like losing their jobs if people discovered they were sick.” Meredith’s traveling exhibition of photos has been enthusiastically received at the many colleges and universities, churches and museums where it’s been shown around the country.

These photographs are part of a growing body of work that photographer Carolyn Jones calls “life affirming work on AIDS.” Jones, who is an advertising and editorial photographer in New York, was approached in April 1992 with an idea dreamed up by George DeSipio, a friend and fashion sales rep who has AIDS: to photograph people with AIDS living positively. “l had always wondered what I could do to help,” she recounts. “lt felt right for me to do something positive, so I jumped on it right away.”

She distributed fliers in Manhattan asking for subjects who wanted to be photographed and “immediately got 30 replies.” Her idea was to photograph people with whatever or whomever they loved, and they showed up at her studio with pets, friends, lovers, and even a basket of tomatoes. “It was so easy to get people to donate things to the project,” she says, “from the lab work clone by Duggal Photo to the food that Dean & DeLuca provided for the shoots. Even the assistants worked for free.”

Her first exhibition of the vibrant black-and-white portraits of HIV-positive men, women, and children, which she calls “Living Proof,” opened on November 30, 1992, at Manhattan’s One World Trade Center. The mezzanine level of the massive tower was transformed by the event from a huge, cold, impersonal space into one filled with laughter and conversation and children shrieking as they ran among the hundreds of people in attendance, the whole thing set to the strains of music played by a jazz quintet. People whose portraits hung on the walls posed alongside them for photographers and for a crew from CNN. Champagne and wine flowed, and even the artificial light seemed warm and embracing. The buoyancy of the event was magical, as if everyone concerned was embarking together on a journey that could transform the hard realities of so many lives. “I’ve never been involved in a project that had so much momentum and the help of so many people,” Jones recounts. “lt’s been an incredible experience.”

Carol Squiers