A nineteenth-century painter, Charles Nègre (1820-1880) may be considered one of the first French primitive photographers. He experimented with all contemporary processes (daguerreotype, negative on paper or glass), inventing a method for photomechanical reproduction. Adapting to these techniques, he was able to achieve mastery of the brand new art.

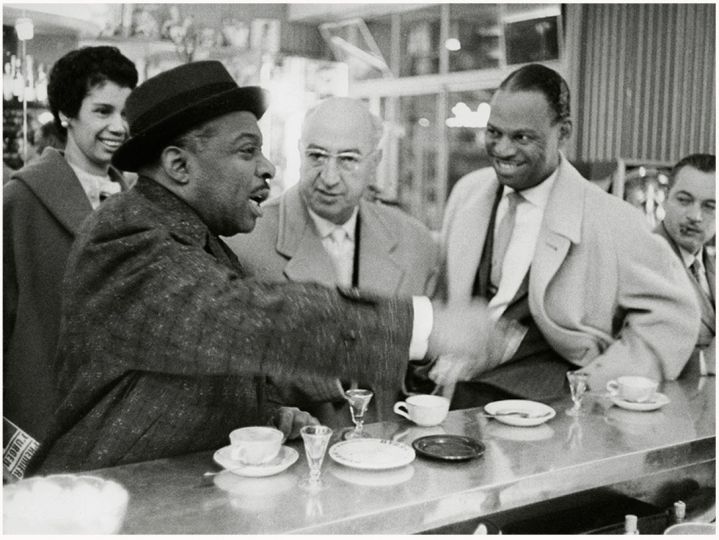

Charles Nègre found out about the daguerreotype process in Paris : ‘In 1844, as I attended one of the sessions of the Academy where images obtained through Daguerre’s technique were being presented, I was stunned by the sight of these wonders and, glimpsing the future promised to this new art, I resolved to devote my time and my energy to it.’ Interestingly, in October 1839, Horace Vernet, his nephew Charles Burton and Frédéric Goupil-Fesquet (carrying his daguerreotype machine with him) had boarded a ship in Marseilles, heading for the Middle East from which they planned to bring back photographic records.

In the last two decades of the twentieth century, during my many visits to Cannes, and later to Grasse, Joseph Nègre showed me a few of his famous great-uncle’s daguerreotypes. These represented plaster casts used in painting academies as study models; several views of Paris; a mountain landscape; some portraits of family and friends as well as a few reproductions of engravings. They were not framed and came for the most part in a half-plate format, either with their original passe-partouts or remounted by Charles Nègre’s nephew in the mid-1930s.

These rare experiments have enriched public and private collections, except for this daguerreotype, kept in the Grasse apartment in the midst of Charles Nègre’s paintings as a relic of his activity as a painter before he turned to photography. Joseph Nègre had found it at the time of our first meetings. In 1985, against my advice, he had agreed to a new, ‘old-style’ mount. This did not fit in what we knew of Charles Nègre’s practice, but fortunately, it was of little consequence. Still, it explains the traces of oxidation, which usually appear on daguerreotypes of the second half of the nineteenth century. Later, in a cardboard box containing some trials by Charles Nègre, we also found a number of daguerreotype copies of photographs. Nègre made these in Paris and in the south of France in the early 1850s.

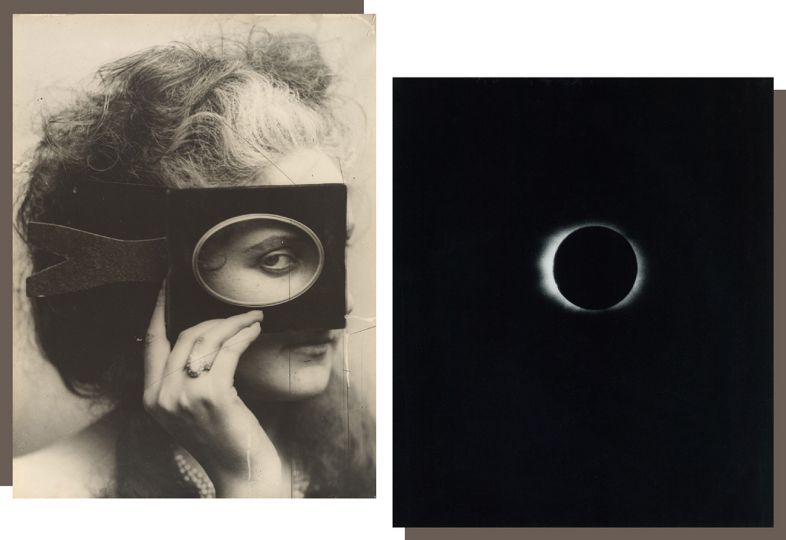

The existence of these plates bitten by chemicals is proof of a will to experiment with intaglio photomechanical reproduction: paper images produced in the camera obscura were then transferred onto a metal plate.

Following Hippolyte Fizeau, Alphonse Poitevin or his Austrian contemporary Christian Joseph Edler von Berres, Charles Nègre had contemplated the use of the daguerreotype as an intermediary medium to achieve acceptable results with the subjects imposed for the competition sponsored by the Duke of Luynes. The daguerreotype described in the note is free of any chemical trace and was not framed as of 1984. After 1850, Charles Nègre gradually mastered his own process for photomechanical reproduction, heliogravure on steel, and no longer tried to use the daguerreotype plate as intermediary. Absent any handwritten or published note in the family archives then preserved, it is impossible to make definitive claims about the eventual destination of the reproduction.

It was important to establish the origin of this unreferenced image. The author of the original painting, Horace Vernet, proved rather easy to identify. Still, a number of details soon showed that the work on the daguerreotype was not exactly the reverse image of the 1835 painting. Two aquatint reproductions of the painting were found. After a lengthy and painstaking work of comparison, it was determined that Louis Adolphe Gautier’s version had served as the original to Charles Nègre. The technical description and the comparison of the three works that follow are provided for information purposes.