I held this conversation with Larry Miller at his home in New Hope, PA, on February 10, 2019, as he celebrates the 35th anniversary of his gallery.

Stephen Perloff:Larry Miller

Stephen Perloff:Were you a photographer first? How did you transition into doing gallery work?

Larry Miller:Let me begin by saying that as a teenager I was hanging sports pictures on my bedroom wall, and this is where the instinct to hang and sequence began. Toward the end of college I got interested in art, started taking art classes, and then discovered photography in my last semester as an undergrad, but was totally in it at that point, and was fortunate that my terrific professor Cavalliere Ketchum helped me get into grad school on one semester’s worth of work. I got my bachelors and my masters at University of Wisconsin to be a photographer, and then Ketchum said, you know, it’s hard to make a living as a photographer, thinking about Life and Look, and the decline of making a living for publications, and so he said you should develop other skills like design and making books, so we all started making hand-made books. So that was an important part of my education, and why I am so comfortable sequencing pictures and hanging shows.

Then I went to the University of New Mexico to get my MFA. …I didn’t stick around long enough but I was there for about a year and a half, got to study with Beaumont Newhall and I was going to be a photographer. With the assistance of my professor Van Deren Coke I curated my first exhibition, on hand-made photography books, at a local bookstore/gallery. After seven years of being in and out of college, I said, “I’m done with college.” I went to Tom Barrow, another of my professors, and asked, “Do you have any ideas of what to do next?” He said there might be an opening at Light Gallery, so that was the trajectory as I did get hired at Light Gallery late summer of ’74 and worked there until 1980.

SP:So was it under Tennyson Schad?

LM:Yes, Tennyson and Fern hired me but Harold Jones was the initial director, and then Victor Schrager took over, and then Charlie Traub towards the end. But I was content to be Associate Director. I just loved dealing with the pictures. You wonder what of my early background is part of who I am today. I just love the pictures, and I was in charge of all the traveling shows. That’s still what I enjoy, organizing and sequencing pictures. The deal making I didn’t really think a lot about, but people told me I could sell a print. I don’t remember doing it, but I’m sure I did.

SP:What led you to start your own gallery?

LM:I was restless, and also Light Gallery was making some shifts in its program, and I was not happy about that. They were starting to embrace what I thought was commercial photography, fashion photography. I’ve never personally had any interest in those things. I didn’t think it matched the idealism Light was based upon. So I was there for six years. I also did some teaching at the New School/Parsons. I kind of thought it was time to go. Aaron Siskind helped me get a teaching job, like a visiting gig, at the University of Texas, I went down there to San Antonio for a semester and taught three or four classes and had tons of time to do my own photography, and didn’t do much. So that was a very rough realization, having been given the opportunity, which I didn’t seize. So I came back to New York and decided the only thing I kind of knew was being in a gallery situation so I became a private dealer. My first letterhead said “Laurence G. Miller, Photography Investment Counselor” [laughs]. That was my first professional identity. I don’t know, it seems kind of funny now, but that’s how I saw myself, as helping people understand how to collect pictures.

SP:Well, that was prescient in a way.

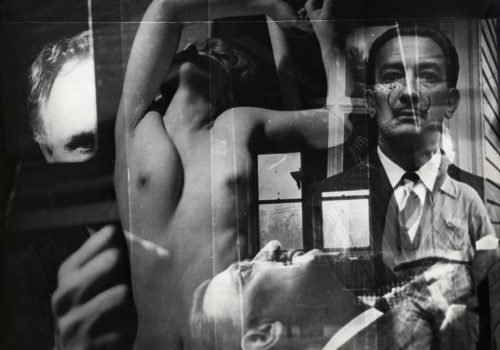

LM:Well, I’m thinking about going back to that now, to tell you the truth — which is later on in our conversation in terms of the evolution of the market. I was dealing privately out of our apartment, then I started representing Val Telberg, who was my first artist, because I knew Val through Light Gallery. When I asked, “Who do I want to represent?” I said, “I guess I want someone who’s got all vintage work and it’s all unique,” because there was so much suspicion about the limitlessness of photography. People had no real education as to how it could be valued, how it be collectible, so Val was perfect. It was all vintage, all one-of-a-kind montages. So he was my first artist and just a lot of fun. I gave Val a one person show at Books and Co. on Madison Avenue. And then came Ray. I had met Ray Metzker when I was at Light, and actually curated one or two of his exhibitions at Light in the late ’70s, and when Light kind of folded I felt that I could then approach any of their artists if I wanted, because I didn’t want to poach in competition with the world that I knew, that I was friends with. So when I started working with Ray around ’82, it seemed like I needed a gallery. I can’t remember exactly why I thought that but I did. And so in January ’84, I opened my first gallery which was smaller than this room.

Val Telberg:Untitled

SP:Yes I remember.

LM:330 square feet, 11×30, and it was great. I started on 57th street. 38 East 57th Street. Victoria’s Secret was two doors down, and I was up in a little space in a building with a number of galleries. Here’s a story not too many people know, but on the eve of my very first-ever gallery opening, my pants split [laughs]. Thank God the woman next door was like this 80-year-old seamstress and she sewed me up and the rest is history.

SP:That’s great!

LM:Isn’t that amazing it happened then? It was really something. A shot across the bow. One of my first shows was The One and Only, Unique Photographs since the Daguerreotype, to confront those lingering suspicions regarding the potential limitless of the medium. And then everything grew exponentially. Pictures got larger, storage capability became larger. And I needed to move, so I moved after a couple years later down to Spring Street. SoHo then was hot, and I stayed there for any number of years until SoHo started getting “mallified.” All the big brands were moving in, and people were starting to go to Chelsea, and I thought Chelsea was just the pits of New York. I remember remarking that the only reason to go to Chelsea was the driving range at Chelsea Piers. I had no desire to go there and I didn’t, and then I moved back to 57th street. And then 57th street a couple years ago was kind of losing its juice, and the building we were in was going to be demolished, so we had to move and went to Chelsea and found this great space. And started to hit golf balls at the driving range. That’s it! That’s the end of the interview, Stephen [laughs]!

SP:What were your hopes for the future when you opened? And did the explosion of the photography market exceed your expectations when you opened?

LM:I honestly don’t remember having that particular thought. Like what is my goal? It was really to represent and to promote — in the best sense to be an advocate for artists that I cared about. It’s still pretty much the priority of my gallery today, as hard as it might be. So, that’s really what I love doing. And um, yeah, I guess make a living, I don’t know. Stop being supported by my wife and try to make a living selling pictures. I found the market to be challenging almost continually. There have been some great periods as well, with my wife Lorraine playing a greater role in managing the Gallery for most of the last decade.

We keep all the old invoices here at the house, and a few weeks ago I found the folders for 1999, and in 1999 I did over 1,200 invoices, and I don’t believe I even do a small percentage of that now. That was great. I don’t remember when each recession was but each recession was deeply threatening. I actually remember, it’s funny because it is so political now, but way back when, when the economy was hurting, and real estate tycoon Donald Trump was defaulting on his loans to Chase Manhattan, Chase called in my $40,000 line of credit, which was keeping me alive. And I remember saying to the banker, this is ridiculous. Donald Trump is stiffing you for $200 million and you’re calling in my $40,000 line of credit? So there you go, Donald Trump. Thank you very much.

SP:What were the most difficult periods and what were the best ones? Other than whether the economy is doing well or in recession, is that the be-all and end-all or are there other things that happened or artists you represented? I mean Ray has a show in Houston that travels….

LM:I honestly just remember it being thrilling and difficult. And again it’s been so many years that I don’t have it all sorted out, but if you picture a wave curve, you know there were ups and there were downs. Maybe the whole highlight of my career was my friendship with Ray, which I don’t think people really understand goes back to 1978, but joining up with Ray on the eve of his big retrospective that Anne Tucker was doing, and being part of that, and then working with him until he died. And I miss that. I miss him.

Ray K. Metzker:Frankfurt, 1961

So he kind of gave me purpose. Ray had his ups and downs, and I had to help him navigate when he would feel like he didn’t feel like working anymore. I would say, “Ray, you don’t have to. You’ve got so much great work, let’s just look at what you’ve got.” And then there were times when he was restless, and I’d say, “Don’t bother printing, just keep shooting! Whatever makes you happy.” You know, that was part of my job was to kind of help him not get caught up in his own blues. As everyone has them in their life, he had them as an artist, really. So that was very special. But consider the list of artists I have shown: Julia Margaret Cameron, Lalla Assaydi, Jonas Mekas, Christian Boltanski, Cartier-Bresson, a fabulous JUMP show by Halsman, Daido Moriyama.

SP:What would you say was the best or most important picture you’ve ever handled?

LM:I’ve been thinking a lot about that. Here’s something that’s quite fascinating, now that there’s the show at the MET of Girault de Prangey. I was invited to go to Paris and meet one of the family members, and in this hotel lounge were his hand-made boxes of some of his daguerreotypes, to see what did I think of them. And I probably shouldn’t have been invited because the person who put me together with this woman said, “You know a lot about daguerreotypes, right?” I always say yes. When someone assumes I have the knowledge, I generally say yes, of course.

So I went and I didn’t know what. I kind of knew they were important, though I wasn’t seeing the great large plates that were the most important, but still I knew, you know, when you’re sitting with the original material of a major body of work that hasn’t seen the light of day, it’s pretty special. But they were already in conference with one of the auction houses, so they kind of went and that’s where that stuff got started, through Sotheby’s and Christies. Just some pretty remarkable numbers. So that was an opportunity that I wasn’t capable of seizing, cause I really wasn’t qualified to be a daguerreotype dealer, but I remember that. I remember telling the woman’s mother where I was staying, and this is like old French money, and she said “Oh, that’s where all the chauffeurs stay.” The rich stay at the Crillon while I was at the Little Crillon where the chauffeurs stay. I was up against people who didn’t want to relate to me easily.

SP:Well how about pictures that you have handled and sold?

LM:I got my parents interested in collecting early, and it’s sad that my dad had his ups and downs financially, and basically sold or donated his collection. It had many great, extraordinary things. Just great stuff. I mean he had like six great Metzker composites, I mean all the top, and he donated them all to great museums. We had this great Stieglitz snowscape, really rare unusual piece at Light Gallery, and I figured if we couldn’t sell it to a regular client after six months, I had a right to kind of buy it myself or get my dad to buy it. I never wanted to compete with Light, but you know, six months should be, you’d show it to Kolodny and all the big collectors at the time, and Menschel, and if they didn’t buy it, it was up for grabs. So, there were things like that: a great Strand Toadstool, a Weston Nautilus, some great Atgets.

My dad was a big fan of Robert Heinecken’s work. So when Heinecken recently had his MoMA show, half the great pieces were from my mom and dad. And my dad would trade with John Szarkowski at MoMA, my dad would trade Heineckens, large multi-panel pieces, for great duplicate Atgets. So we had some nice Atgets. It was fun. You feel sad when you sell something out of your personal collection, and when you get the check you feel good and you move forward, otherwise you’d have to hunker down.

SP:You talked a little bit about the conditions that led you to move from one place to another.

LM:Well the whole industry has changed. You want to talk about the state of the market?

SP:Yeah, yeah.

Helen Levitt:NYC, 1939

LM:A saying I know myself and other dealers have been saying for at least five years, is in the old days, the early collectors would care about what’s on the back of the print and today the new people only care what’s on the front of the print. So we are increasingly dealing with people in their 30s and 40s of ample wealth, looking to buy photography to hang in their home or one of their homes, or their beach home. Now we have two people with new homes in the Hamptons, and they want pictures of water or this or that, and for one reason or another or because someone is leading them to us, they come in and they’re interested in some of our artists like Toshio Shibata or Luca Campigotto, that sort of thing. But to get them interested in a little Ray Metzker vintage print of the Kayak, ya know, or Helen Levitt’s three kids with masks, it’s just too small, too dark, and why would they want a black-and-white picture of a boat or poor kids on the stoop.? So there’s a real evolution away from that kind of connoisseurship into more of a decorative function, which we’re all coming to grips with in one way or another. I feel like I’m the guy at the helm of this giant ship and it doesn’t want to turn very quickly. But it must continually change its course as the tides change. Even after 35, 40 years I’m still trying to understand navigation — and be true to my own journey. The same way with Light, I would not start showing fashion photography. If fashion photography became the mandate right now. If the whole art world decided that we’re done with gender, we’re done with race, now let’s just get into fashion, I would certainly go somewhere else.

SP:Well, it had that period with Avedon and Penn and Newton and everyone else, and it’s still hot to an extent.

LM:I’ve never had an interest in Irving Penn or Richard Avedon. This is probably my biggest financial weakness, is I always loved the Ray Metzkers and the Helen Levitts of the world, who didn’t want to go and become ultra-successful, and then spend the rest of their life proving they were great artists. Helen and Ray, they just wanted to be artists, and that humbleness, that humility, is really what inspires me.

SP:Well I think that makes for richer relationships.

LM:Well richer for one way and not richer for another way. Sometimes I wish I did the other way. This is important to me and you can include it or not, but when I turned 60, which was 10 years ago, it was an interesting time and I was trying to understand, having a son, I was trying to understand what my relationship was with my father, now that I’m a father to a son. This was the beginning of my own internal conversation. And then I was thinking about how did I end up being who I was. Where did it come from? When I went to college I really wanted to be a civil rights lawyer. I was studying sociology, criminology, I devoured that stuff. But then I realized I wasn’t a very good reader, and was kind of sick of taking Latin. I don’t know. I just knew it wasn’t for me. And then eventually it evolved into art.

And when I turned 60 I finally understood what it was all about, that what I really love doing, to this day, is being an advocate for people who need me. Richard Avedon and Irving Penn don’t need me. Helen Levitt needed me, in her own, wonderfully eccentric way. At least to play gin rummy on Monday afternoons for a penny a point. She usually was the big winner. And Ray needed me to fulfill a certain role with him. And Val Telberg, so that’s why I really don’t have any super A-lister names. I mean I represented Ed Burtynsky. All Ed was interested in was commerce, business, do more…every spring he would come to have lunch with me at Art Chicago. “Larry, I see this guy Gursky, he’s in four booths. How come I’m not in four booths?” I don’t wanna be your dealer. What’s the point? There’s always somebody else looking for the high-selling artist.

I want to give my skillset to artists who really enjoy it, and I can give them a bounce. I’m trying to do it now with this Iranian woman I met in Santa Fe at that portfolio review in November, Fatemeh Baigmoradi. Everyone was coming to my table and they got their iPads and their books and they’re all ready to go take the next step to stardom. And she comes in and has this box filled with burnt photographs. And I knew this was someone interesting. This is raw, this is, she doesn’t have it all figured out. That motivates me. The rest is just commerce and it’s never really been my priority. Unfortunately at times. The joy is to not only help someone get to start in a career but help someone get a visa. I had to help this Iranian woman get a visa, and that’s hard right now. So suddenly my role changed. My role, and I’ve had to do it two or three times throughout my career, write letters to their lawyers to try to help them be able to stay in the United States. And it’s much harder now. A lot of people are fearful.

Fatemeh Baigmoradi:From It’s Hard to Kill

SP:Yeah, I’ve done it a couple of times for artists. In the past it wasn’t quite so hard.

You’ve also done a lot with Muybridge. How did that come about?

LM:I’m a sucker for grids. That’s one of my composites [pointing to the picture on the wall behind him]. Ray was my influence when I was in college. I was doing composites, but I couldn’t get my lines to be parallel. Poetry in a rigid setting is what interests me. I have six or seven of these tin plates that you press chewing tobacco, and then you buy your square, and the square would have this thing impressed in the top of it. Days of Work, Browns Mule, and I’ve got six or seven of them. So this to me is Muybridge, this to me is Metzker. This to me, is me. This is what I dig, you know. And they’re like Warhols to me, too. Taking the ordinary and repeating itself enough that it becomes meaningful and lyrical. Muybridge is so fascinating in so, so many ways.

He published 763 different plates. The last one is he torpedoed a chicken. And all I could think of was, if it was me, I would’ve torpedoed that chicken after around 50 or 60, but to do the same thing 763 times takes a lot of patience. I still think Muybridge is misconstrued. He was a vaudevillian. There are certain pictures that must have never been sold cause they never emerge other than we see them in museum sets. But he did pictures of people pushing donkeys, having a horse jump over three horses, he had a mule on a seesaw. If you go through and look deeply, look at all 763, the guy was nuts! There are lots of people pouring water, so that’s what interests me the most is Muybridge had this weird, comedic instinct in him to do really bizarre things, and I find that appealing.

SP:He’s kind of the Groucho of photography in a way.

LM:More like Charlie Chaplin. He is like the week before silent film. I don’t know if you ever saw this. My nephew is in digital video, so we put together with a soundtrack this minute-and-a-half movie animating about ten Muybridge sequences. So when I was doing some business with Michael Wilson, the James Bond producer, I said, Michael I want to share my film with you. It’s only a minute and a half long, but he enjoyed it. So we animated them, and what’s truly remarkable is to see them animated because when you see someone walking and you’re just looking at a picture, they’re walking back and forth, but when you see them animated, they’re going back into a space, turning around, pivoting on their walking cane, coming back, they’re really quite amazing. And you just feel that cinema is a day away, when they just get it going. And there are hilarious ones, I mean really ridiculous ones that were so much fun.

So Muybridge is great, and Muybridge appeals to everybody for everyone’s personal reasons. So when we did a one-person Muybridge show at the Art Dealers Association Art Show at the Park Avenue Armory, we were selling everything to everybody. I mean the art dealers who had horses were buying them. Adam Weinberg, the Director of the Whitney, bought one of a contortionist. So I love Muybridge because they’re just fun, but affordable. More often than not we’re asked why they are so cheap, rather than why are they so expensive. There are just always surprises in them, if you look at one long enough. So you see a guy doing a high jump, and suddenly you look at it for the tenth time and you realize his hands have hit the strings, the strings that are providing this gauge of scale. It almost looks like he is playing a harp! Or there’s ones where there are birds flying. There’s all this crazy stuff. I like crazy stuff.

Gary Brotmeyer:Staghound (The Sporting Scene)

LM:Where am I going? I’m going do a one person Gary Brotmeyer stand at the Armory show. One of my all-time favorite artists, very idiosyncratic.

SP:Yeah, I remember. I’m pretty sure I saw the first show.

LM:In ’86 I did my first show,Make Believe History. It’s right on target again today. So I’m working with Gary. I always loved Gary. I’m real optimistic that people will buy out our stand. I go into every art fair believing I’ll be successful. If you go in believing, “I just want to get by and pay my booth cost,” why bother? That’s not a way to live. You’ve gotta go in believing it’s going to be great. If it isn’t, after 40 years, you win some, you lose some.

SP:So do you know Marvin Hoshino?

LM:Sure!

SP:He’s one of [my wife] Naomi’s editors. She’s the copy editor for Ballet Review.

LM:So Marvin has been, or was, Helen’s closest associate. I don’t know the perfect word for his role, but it was essential. I had to work pretty much with or through Marvin, and I had been kind of cautioned about it in the beginning, so my approach was, call him up and say “Marvin, I want this thing to work!” I wasn’t going to go in saying “I’ve got this big ego, don’t get in my way.” No one got in Marvin’s way. It just wasn’t gonna happen. He was very close with Helen. She depended on him. So Marvin and I are still good friends, but you know, her archive decided to go somewhere else, which I thought was a crazy decision, to have Thomas Zander, wonderful dealer, friend of mine, became the representative of the Helen Levitt estate based in Cologne, and it makes no sense at all. She’s a New York artist. So after being kind of pissed about it I ended up just selling a bunch of stuff to Thomas in Cologne, and like with Ray, I really know where everything is, so I have no shortage.

Out of the blue, James Agee’s daughter-in-law contacted me, probably googled me. If you google Helen Levitt, you get me a lot faster than you get Thomas Zander. And she came up to New York, and we did this wonderful Helen Levitt five decades show a few months ago, about twenty pieces that were given to James or his son John, which was her husband. So they’re all gifts to the family. Really beautiful group of vintage prints.

It’s a hard time for most galleries. There are too many galleries, too much art, too few this, too few that. I used to get everything listed, if not reviewed. The New Yorker, New York Times— it’s done. I can’t even get their attention anymore. So I don’t have any free press. The curators of my generation have pretty much either died, retired, or are wrapping it up. I mean I’m lucky to have Keith Davis, curator of the Hallmark Collection at the Nelson-Atkins Museum, as such a close friend of mine, but he doesn’t have the money he had up until a year ago.

Larry Burrows:Reaching Out, Operation Prairie, Nui Cay Tri, 1966

One of the coolest things I ever did have was, because of my relationship with Larry Burrow’s son Russell, one of the great shows I ever did was my first Larry Burrows show, which was one of the very first shows anyone did about Vietnam. To this day I’m still very close with his son Russell. And Russell and Burrows and the whole Life Magazine, Time, Inc. community is still quite strong. Eisenstaedt was very close with Russell Burrows’ wife at Time, Inc. and she was like Eisie’s right-hand person. So through Russell’s wife I met Lulu who is Eisie’s sister-in-law. Eisie and his wife never had children, so a lot of Eisie’s stuff went to Lulu, including the suitcase that Eisie brought to America in 1935, this beautiful purple leather salesman suitcase, with about 90 photographs, hand-printed, all mounted, signed, matte surface, his master set of his European work. And I sold it to Hallmark, to the Nelson-Atkins, and they’re going to do a show of it. I think that was one of the greatest things, was that this is what this immigrant photographer came to New York with, went to Henry Luce and said, “Hire me” and Alfred Eisenstaedt had more covers of Life Magazinethan anyone. That was cool. And I still have these things because of my Burrows connection. There are still things pending in Europe. In South Africa, the kids of the kids, the nephews of some of these, it’s really quite interesting. One very big global family.

But I don’t know how many more shows I’m going to do. They’re not providing me with a livelihood anymore, the shows. So I gotta think about that now. I’m trying to understand how not to do shows and still be vital. I think I’ve done enough. I’ve done over 250 exhibitions. I’ve shown over 1,000 people.

On the positive side, I’m getting a great Kerry James Marshall back. I think Kerry James Marshall is an extraordinary painter. And he did some photography, and I was able to find a print from his first dealer ever. Sold it to a good client of mine, and now I’m getting it back to put in our anniversary show. Just this beautiful portrait…dark…so that’s fun.

I most enjoy the periphery of photography. That’s why Brotmeyer interests me. Even Muybridge, in a sense, was more science than art. Kerry James Marshall, you know, Warhol. I’m trying to do something with Hockney. So that’s really what keeps me excited. So I have to find a new way to do that.

SP:You probably will.

LM:I don’t know if I have a choice. I can’t just wrap it up and retire. So that’s my challenge. That’s why I sit down here in my man cave and try to forget about everything, and I’ll wake up tomorrow morning and, like my Graceshow — I woke up at 4 in the morning and said “Grace, I wanna do this show. Yeah, Grace, that’s a good title:” Grace: Gender, race, the e”” was identity. It was that fast and easy and I knew 100% that was my next show. So I like waking up early.

SP:Yeah, when you get ideas like that.

LM:I do! They pop up fairly frequently and a lot of them you have to toss out. They don’t substantiate themselves, or you can’t execute them.

Ray Metzker was a great inspiration as well. He had such a playful and lyrical way of titling his different series: Pictus Interruptus, Whimsy and Wispy, City Drillers, Feste di Foglie, Hula Cola, and so much more. I enjoy the sound of show titles — one of my recent best was When Harry Met Aaron.

SP:That’s one of the great things. You never know when the next great idea will be.

Laurence Miller’s 35th Anniversary exhibition, ReCOLLECTION, featuring nine Ray Metzker masterworks,

from March 14 through April 27 with a reception on March 16, 2–5 p.m.

The gallery is located at 521 West 26th Street, NY, NY 10001, (212) 397-3930, Hours are Tuesday to Saturday 11 a.m. – 5:30 p.m.

http://www.laurencemillergallery.com.