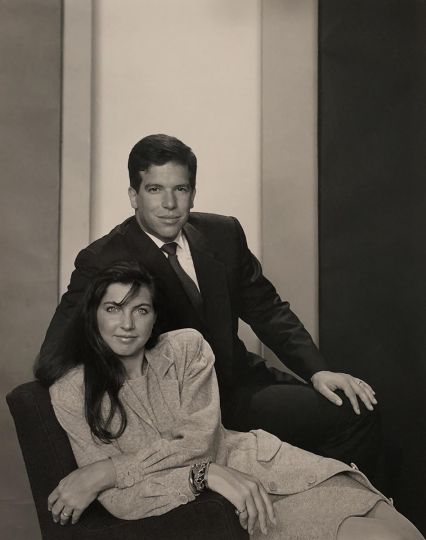

Earlier this week, Barbara Baker Burrows, the former director of photography of LIFE magazine, passed away on Martha’s Vineyard after a long illness. She was 73.

“Bobbi,” a veteran of LIFE since the 1960s, was a rare breed: the den mother of the great LIFE photographers (from the magazine’s weekly and monthly incarnations), a curator, a book editor, a photo historian, and the daughter-in-law of the legendary war photographer Larry Burrows, who died in Laos in 1971 covering the conflict in Southeast Asia for LIFE.

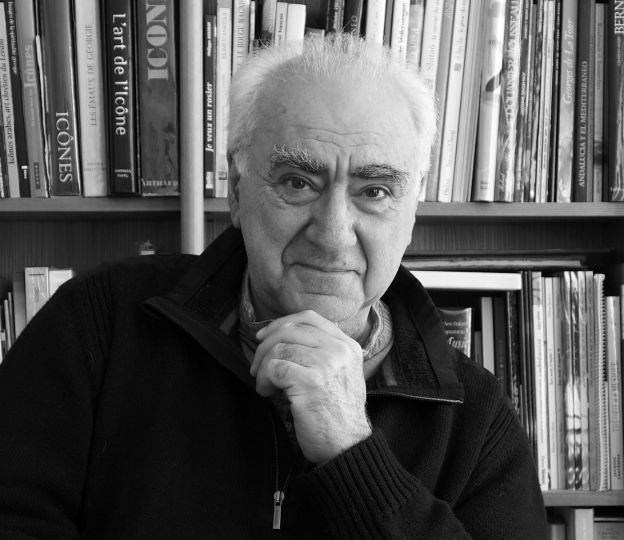

Burrows’s closest friends were often the photojournalists she championed, many of whom were the chroniclers of the visual history of the 20th century: from David Douglas Duncan (who turns 102 this month and, until Burrows’s death, dutifully telephoned her each week) to many of the stars of the LIFE firmament who have passed on, from Gordon Parks to Henri Cartier-Bresson, Martha Holmes to Mary Ellen Mark, Lennart Nilsson to Bill Eppridge. Burrows (along with LIFE publisher Charles Whittingham and archivist and curator Doris O’Neill) helped turn Alfred Eisenstaedt into a household name by using LIFE magazine, exhibitions, and books to reintroduce and showcase his incomparable archive to a new generation. Burrows, in 2004, was at the bedside of Carl Mydans (who, in World War II, had famously depicted General Douglas MacArthur wading ashore at Luzon in the Philippines) when Mydans died, at age 97.

She had a keen eye for new talent and would jump-start the careers of dozens of young, enterprising photojournalists who would stop in at her bustling office at LIFE, show her their portfolios, and then depart, having acquired a new mentor. Known throughout the photography community as a person of compassion, principle, and limitless generosity (of time, spirit, and counsel), she was also blessed with a sense of humor and mischief. It was her delightfully macabre habit, when phoning up certain friends, to leave her call-back number with their assistants, giving not her own name but the name of a deceased photographer. (One of her favorites: “Tell him Rudy Crane called.”)

“What I’m going to miss most about her is her chuckle—that lovely laugh,” confided Burrows’s friend John Frook, a LIFE editor who began working with her in the 1960s. “Every time I saw her she was bent over a goddamned loupe. She cared mightily about pictures. She just loved pictures. And she spent a goodly amount of time making photographers look good.” Her former colleague Mary Steinbauer, a LIFE assistant managing editor, concurred, recalling Burrows’s “doggedness in pursuing a picture—in acquiring a hidden treasure. If we heard [that someone had taken a great photo that no one had yet published] and we wanted to see it or use it, she was on the case.” Steinbauer insisted that she would sorely miss Burrows’s “sense of fun, her mischievousness, her teasing… her positive attitude” but also “her loyalty” as well as “her great sense of right and wrong.”

In the view of her longtime friend, photographer Donna Ferrato, “Bobbi will be best remembered as the guardian angel of all the photographers who worked with her—the shepherd of their work, of their whole beings, from the day she met them to the day they died. She adored photographers and photography. She met [the greats] when she was a young girl. They grew up—but she stayed that young girl. They left the building, but Bobbi remained, looking after their work, their legacies—even their children.”

What’s more, added Ferrato, Burrows “had that aristocratic sophistication, coming from photo ‘royalty,’ having a war photographer in the family, who died in the line of duty. She took that respect forward, respecting everyone she worked with. No one is like that today. Plus, she was sort of the Debbie Reynolds of photography—genuine sweetness.”

Burrows was a giving soul, validating the legacies of scores of photographers by advocating for them and their oeuvres; supporting her fellow picture editors and photo researchers; advising mid-career photographers about their assignments, their career decisions, and their personal lives; charitably giving back to the field of journalism; and tirelessly providing years of service and sacrifice to the company that employed her, Time Incorporated. “She gave Time Inc. everything she had,” said Frook.

Burrows, according to her photographer friend Harry Benson, “had a legendary photographic memory—and a work ethic to match.” She spent so much time in the Time-Life Building that she was perpetually late to the many parties and social functions she attended—because she had a knack for staying at work “just one more hour” to help out someone from the extended LIFE family (a former editor, say, or a descendant of a late photographer) who had telephoned to inquire about an old photograph or a wayward tearsheet. “You could go up there with film at eleven o’clock at night,” Benson remembered, “and she would still be there.”

Burrows was a confidante and picture editor of many legendary photographers still shooting today. She kept numerous White House photographers—and portraitists for the British royal family—on speed dial. And she was a close friend of countless photojournalists who are no longer with us: Slim Aarons, John Bryson, Eddie Adams, Theo Westenberger, Ken Regan, Henry Groskinsky, George Silk, Ralph Morse, Grey Villet, Brian Lanker, Enrico Ferorelli, Philip Jones Griffiths, Rene Burri, and others too numerous to name. Her prodigious output at LIFE was matched by the many books, “book-a-zines,” and special issues she produced. At one point in the 1980s, she created a visual news section for LIFE—a “magazine within a magazine”—working with a young writer named Graydon Carter. Their monthly feature, Newsbeat, would become the template for a start-up publication called Picture Week, the brainchild of Burrows’s friend and colleague Richard Stolley.

Burrows often charmed the celebrities she covered, spending long hours with the likes of Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman. And she socialized with a wide circle of famous friends on Martha’s Vineyard, a group that, over the years, would include writers David McCullough, Art Buchwald, and Bill Styron; musician Carly Simon; editors Eleanor and Ralph Graves; TV personalities Mike Wallace and Walter Cronkite; her beloved Alfred Eisenstaedt and his sister, Lulu; as well as Burrows’s best friend, Ann Morrell, a veteran LIFE mainstay, who, as it happens, predeceased her by ten days.

Barbara Baker Burrows is survived by her husband, Russell Burrows, daughter Sarah, son James, daughter-in-law Emily, and two grandchildren, Knox and Haven. Russell and the family, in fact, made Burrows’s last, challenging months not only bearable but full of love, joy, and meaning.

“There were three loves in her life,” observed Harry Benson. “First, LIFE magazine. Second, she loved photographers: she looked after Eisie [Alfred Eisenstaedt], went to the hospital to look after him; she would swoon over photographers like George Silk, Dmitri Kessel, and Gjon Mili. And, third, she loved [her husband] Russell. She was the sweetness in Russell’s life.”

David Friend

David Friend, the former director of photography of LIFE magazine, is Vanity Fair’s editor of creative development and the author of The Naughty Nineties: The Triumph of the American Libido.