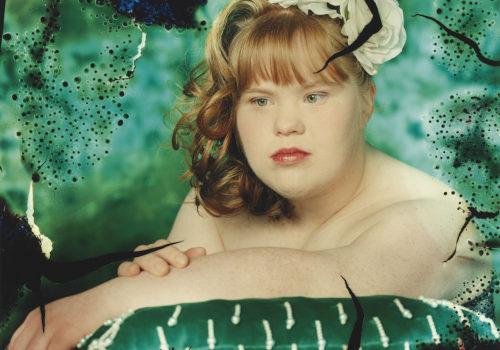

His modern vision of documentary photography influenced generations of photographers. The American Bruce Davidson, now 84 and a Magnum member since 1958, is the 2018 recipient of the Lifetime Achievement of the ICP Infinity Awards. In 2013, The Eye of Photography interviewed the photographer, who welcomed us almost timidly into the living room of his apartment on the Upper West Side, his books laid out on his lap. A few days later he flew to Los Angeles to photograph the mountains that surround the city. Also, at the end of 2012, Davidson’s wife, Emily, published a biography of Bobby Powers, entitled Bobby’s Book, who was the head of the gang Bruce followed for his work during the latter series in the 1960s. The book also includes a few rare photographs, including one of Powers’ mother. Today we share again a version of this interview.

Let’s go back in time and talk about Brooklyn Gang…

Yes, I spent a year photographing this group of trouble teenagers. I almost hesitated to call them a gang, they were really depressed, angry, frustrated. They were basically from poor families, families who were addicted to alcohol. 40 years went by and I got a phone call from the leader of the gang, Bobby Powers, who wanted to meet with me. My wife said “I must go with you”, to protect me (laughs), and we had lunch in Manhattan. This person went to hell and back. After I left, he became a notorious drug dealer, abuser, was about to die on the Brooklyn waterfront just before going to detox. And now he’s 65 years old and turned out to be a drug counselor. Then he came here for ten years and talk to my wife Emily. That’s the book that just came out. The photographs are also interesting, pictures of him angry, pictures of me taken by him as well, some of these did not appear anywhere else.

Is he someone you can talk about?

Sure. Well, one day I asked Bobby what was his mother like. He described her as small, smoking cigarettes etc. And I went back to my contact sheets because I had this picture of a woman, who looked like her, made a print and showed him. And it was the only picture ever made of his mother. It’s not in the Brooklyn Gang book but in his biography now. (laughs)

If you talk about family, we can talk about your daughter, who’s also a talented photographer…

She’s photographed farmers, made a book about it. People don’t see her as a photographer but as part of their community. She’s also done some very good work in Cuba a few years ago. I learned from her to be entirely truthful.

When you look back at your early pictures, do you still learn something new from them?

Oh absolutely. Photographs can have other meanings than what you think at the time. For instance, I wanted to photograph the New York harbor. The only way to do this was to get an assignment from National Geographic, because they have a lot of money and I could spend six months on this project. So I photographed the Statue of Liberty by night. I found a point of view on a pier where the statue would be right in the middle of the Twin Towers. At the time, it was published as a kind of ironic contrasted picture, because critics about the World Trade and its architecture were very snide. We were almost making fun of it through this little absurd view. But after 9/11, the towers became sacred and this photograph very iconic: in a sense the Statue of Liberty would become their guardian, trying to preserve them from future violence.

There’s both rawness and poetry in your vision. How would you qualify your pictures?

I think each body of work has its own atmosphere. For example the Widow Of Montmartre pictures, made in 1956, are very romantic. It was the very first moment I met Cartier Bresson in person. Brooklyn Gang is very raw and tense. Subway is also tense but humorous, there’s a certain irony. The subway could be anything: someone’s studio, it could be a violent place, a poetic one, a sexual one. By the way, it was at a time when the city needed to improve the subway system. People would tell me: ‘oh you’re doing something about the subway, well very good idea!’

Do you think it still needs improvement?

Well, it’s not that dangerous anymore but on a rainy day like today, it can be bizarrely very slow. But if you compare it to the Paris subway, yours doesn’t run 24 hours and the seats are so small! (laughs) Another story: when I did the pictures of Queen Mary II in New York, I used to go down to South Ferry to catch it arriving in the bay and then run into the express subway uptown to get a different view of it being birthed. It was a lot of fun!

I guess it was more nerve-racking on East 100th Street, the title of one your series, right?

When I first printed this series, I made it very dark. I wanted these pictures to be like bronze statues from the MET. The emotion was so heavy there that I almost didn’t want to see anything, I wanted to feel it. Years later, I realized that I was losing a lot of information and printed them lighter so you could see for example a boy’s face that you did not see in the first ones. But there’s this minister, that I still know, who’s 93 years old, and was at the time a very important political figure in Harlem. He told me it was seen as the worst black neighborhood in the city but he would see it as the best black one. And it’s true; the spirituality of the people was fantastic.

At that time, what really led you to focus on poor communities?

I didn’t see them as poor. They may not have had a lot of money but they had a wonderful vitality. I was drawn to it. It seemed very real to me.

Was this world more real than yours?

Well, my mother was single; she worked in a torpedo factory during the war. We lived with an uncle. We were basically poor as well. I was always in touch with need. I think I always had this empathy for people who are disfranchised, challenged in some way. Bobby’s story is incredible, everyone would have thought he would die; he’s taken every drug known by men.

You never tried anything with him?

Oh, my wife and I even rarely take an aspirin, you know! (laughs)

Stupid question, but do you have favorite photographs?

Stupid answer: my favorite photograph is always the one I’m taking. (Rires)

To you, what is important to be seen nowadays?

Today, I guess photographers should relate to the environment. There are certain things that draw me, like the gorillas in Africa, the polar bears in the Arctic. It’s important to roam the world and explore it with empathy. It’s what my photography is only about.

Interview by Jonas Cuénin

https://www.icp.org/infinity-awards