It was 1980 – I was 27 and I wrote to Irving Penn, asking if I might come and see him. I had just returned to New York from four years as a photographer, printer and gallery director in Paris. I was starting a publishing company to make books by great photographers and artists. I wanted to make their pictures sing on the printed page. I dreamed of publishing Penn’s work. He was 63, at the peak of his powers after a 40-year career, and I revered him as a great master. He wrote me back a handwritten note, which impressed me no end, inviting me to meet him for a sandwich at his studio. I brought along my first book, and he looked at it for no more than thirty seconds, closed it and handed it back, saying courteously but firmly, “Thank you, Mr. Callaway, but I have to tell you that I have no interest in the kind of book you are making.” The meeting was over, and not knowing what to say as I retreated towards the door, I asked him, “May I show you my next book? Maybe you’ll like that more.” He smiled and said, yes, anytime.

And for the next two years, every few months I brought him my latest book. Each time he would stare intently at the pages, often with a loupe, and pepper me with questions about the printing method, the paper, how many passes of ink, what line screen, the size of the print run. And each time, he would hand the book back, thank me, and invite me to return. Of course I called him Mr. Penn, as everyone did. He called me Mr. Callaway. I think Penn saw in me an apprentice and protégé, who was as obsessed with making the photograph sing on paper as he was.

In 1982, I published a book on Alfred Stieglitz. I later learned Penn had gone to see Stieglitz at An American Place as a journeyman photographer in the 1930s, and subsequently photographed Georgia O’ Keeffe ( whose work I later published). The book was printed to a very exacting standard of fidelity. Each plate was proofed in ink before going to press ( printed before being printed!), the tone and color matched precisely to the original print in four layers of ink, the text printed in Monotype letterpress and the paper custom manufactured to a special texture, cast and weight. I did not tell Mr. Penn I was working on the book, but brought him the first advance copy. He was speechless, stared at each plate silently, and after about thirty minutes, he looked up, extended his hand, and said, “Congratulations, Nicholas, this is a fine piece of work.” It was the first (and one of the few) times he called me Nicholas.

In 1983, I met Issey Miyake, another master in my eyes, while working on the book Eiko by Eiko with the great Japanese art director Eiko Ishioka in Tokyo. They both revered Penn as I had, since their student days in the 1950s, but had never met, and at their request I arranged a meeting the next year in New York.

Miyake asked if he could commission Penn to photograph his fashion – he would not presume to interfere or art direct the shoots in any way – he would not even attend them; what he hoped for was a pure creative collaboration, a silent conversation he called, “A-Un”, in Japanese. Eiko showed Penn our book, which intrigued him a great deal. It marked the start of an A-Un among the three of us, and a long friendship. It also marked the beginning of my working relationship with Penn.

Five years later, in 1988 we published a book of that collaboration between Miyake and Penn, which continued for years thereafter. It was an unusual example of East meeting West: an American photographer with Zen-like refinement and rigor interpreting the chef de file of the Japanese avant garde. Produced by Jun Kanai and designed by her husband Kiyoshi Kanai, it was printed in Kyoto and released in New York, Tokyo and Paris to accompany Issey’s retrospective, A-Un, at the Musee des Arts Decoratifs in Paris.

I then asked Penn if he was ready to do his retrospective. He said, “I will do it only if it sets a new standard for fine printing and book making. Don’t let me down, as I imagine it will be my last book.”

For the next four years, I spent thousands of hours with Mr. Penn and ” the work”, as he called it. We assembled a small, but extraordinary team of his assistants, our researchers, editors, designers and printing craftsmen, including Thomas Palmer and Richard Benson, the world’s greatest photographic printmakers. We plumbed his archives – hundreds of thousands of pictures – and selected the optimal print for each image, whether it be transparency, contact print, platinum, or dye-transfer print. Penn oversaw every millimeter of the design (he had begun as a graphic designer under Alexander Liberman ); he laid out every picture, and every line of type (in Univers Monotype). But he left the book’s printing to me, and we spent over a year in the proofing stage alone. I would bring signatures for his approval, and he would dive with delight into the sheets with a loupe, checking to see if the registration was off by a hair, especially in the thumbnails in the index pages. We developed a new method for both black and white and color – 10 impressions of ink in all – and two layers of varnish. Some books are blessed in their production and some are cursed. This one was sheer hell: everything went wrong – I think because we were taunting the printing gods. My team and I supervised on press 24 hours a day for three months. In the midst of it all, Hurricane Bob blew over us. I dubbed it Hurricane Irving. My daughter was born the week the book went on press.

He made the image of the yellow and green gingko leaves especially for the jacket, and called the book Passage: A Work Record. I brought Mr. Penn the first finished copy to his studio, as I had so many others in the previous ten years. He looked at it for about an hour, and said, ‘Thank you, Nicholas, but I guess it’s not quite what I was hoping for”. I apologized for letting him down. Although dismayed, I understood how he felt, because anyone who has seen their work translated into print knows that there is a kind of post-publication letdown. After all the dreams and hopes and work that one has dedicated to making the pictures come to life and to “making the page sing”, finally it can only be an approximation, and not the thing itself. But the physical object can contain something of the emotion and spirt that went into it. Looking back, I think that Passage does sing- in a melodic, if elegiac tone.

Passage was published in November 1991 in seven languages, at a list price of $100.00, and was accorded a front-page review on The New York Times Book Review.The economy hit a speed bump that fall and some of the copies were remaindered. Now, copies in mint condition can fetch up to $2,000.00.

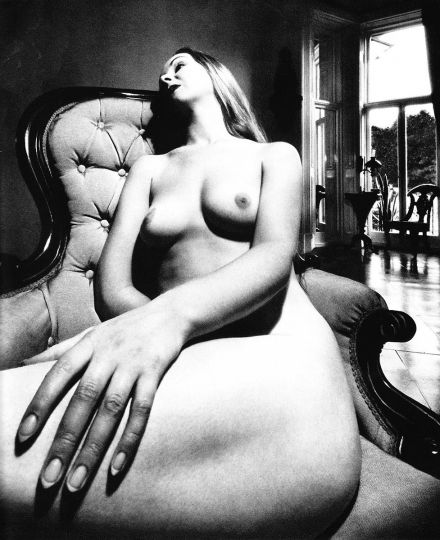

He dedicated the book to his beloved Lisa, his wife, model and muse who graced so many pages of Passage. She called me to tell me how much she loved the book. She passed away three months later, and Mr. Penn never quite recovered from the loss of his true love. We made a memorial book of Lisa’s sculpture in a few hundred copies that Mr. Penn sent to friends, each with a handwritten note. In his final years, I continued to go see him – as always, over a sandwich lunch at the studio. He wanted to see each new title I published. With each visit, he would bring out a copy of Passage and praise it more highly, becoming wistful as we looked over it together. He said “The book is everything I wanted it to be. I would not change it a bit.” He spoke of how fortunate he felt to have been part of an era and a culture that had since disappeared. One day, he looked at me intently with moist blue eyes and said in his low dignified voice, “Nicholas, don’t waste time on the unimportant things. It’s the work that remains.”