One of the exhibitions selected by Jean-Louis Pinte for the European Month of Photography is Agence VU photographer Jean-Robert Dantou’s Objets sous contrainte. Curated by Christian Caujolle, this new series about madness is the latest installment in the ongoing project which Dantou has been working on for years with a team of social scientists led by Florence Weber, a professor at the Ecole Normale Supérieure and a researcher at the Centre Maurice Halbwachs. Today L’Oeil de la Photographie is presenting a selection of photographs and testimonies taken from the 36 works in the exhibition.

Read the full article on the French version of L’Oeil.

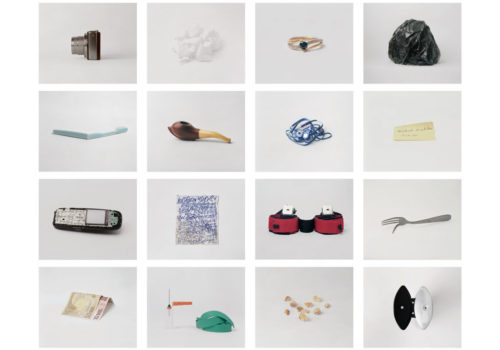

Translation of captions in order :

#01 • AGATHE’S TOOTHBRUSH •

It all started here, with Agathe. She told me about her husband, who was diagnosed as bipolar years ago and from whom she has since separated. For a long time she didn’t talk to anyone about it, and then she got over it. Agathe had three daughters with this man, lived with him for ten years, and remembers her own doubts, his various crises, fits, attacks, outbursts, then spells in hospital, some willingly, some forced. For a long time, she didn’t understand what was going on right in front of her. She no longer knew how to make sense of certain situations. One evening, her husband came home with boxes full of lp records that he had bought on a street corner : Sosa Mercedes , Chico César, Chet Baker, she liked them but found it strange, so many records all at once. A few months later, he changed all the living room furniture without warning. He started impulse buying, talking about things that were out of character, it unnerved her. When she raised it with him, he reacted badly, told her she was worrying about nothing. One day, these acts took the form of broken objects in the house : her husband had smashed in the doors of the living room cupboard, knocked over all the lamps and snapped her toothbrush. That was the day she understood that the problem was bigger than her. This broken toothbrush, the object of a life that was cracking up, was a trigger : on seeing it, Agathe decided to convince her husband to go to a psychiatric crisis service. It was on meeting her that I decided to follow this trail of objects that I would later call « marker objects » , objects of friction which grate and speak of tipping points, of realisation and decisions to be made.

#02 • THE ANONYMOUS PIECE OF PAPER •

For several months, I spent time in a home in the South of France for people who have just left psychiatric hospital. The home takes people in who have nowhere else to go, who have cut all ties with friends and family, and whose only choice when leaving hospital is to live on the streets. There are thirty people in the home, they have the keys to their rooms and can stay for a maximum of a year. As well as the permanent residents, the home receives twenty or so ex-patients every day who benefit from meals and the activities of the home. The team allows 6 months for the new arrivals to « land, to start finding their feet, bearings and trust ». Then work with the nurses, social workers, caseworkers and psychiatrists begins, to try and « rebuild a life plan », or at least a plan for a place to live. At the beginning of my stay, I came across this piece of paper on the floor of the lift. I kept it in my notebook for several months before photographing it. I regularly looked at it and tried to decipher it, without ever managing to. And, as is often the case in the home, I see myself in this object : my scribbles, my foibles, my endless list of things to do which, after several weeks, become totally illegible, even to me. This object, like some of the others, comforts me : it’s not so serious for me. It lets me carry on doing this, lets me keep madness at a distance from the rational world, reassuring me as to my own sanity.

#03 • ANTOINE’S PIPE •

Antoine is in his 30s. After being a brilliant middle school student , he dropped out of high school on the death of his mother, and closed up. He then went through a long period of depression . He spent an enormous amount of time on his computer, and when he turned 20, was hired as a developer in a company with 1,500 employees. He lived in a bubble in front of his screen, and told me that he managed not talking to anyone for nearly two years. There then followed periods that he describes as «profound social and emotional withdrawal » which lead him to several years of hospital stays : forced eight times and three of his own free will. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia. I get on well with Antoine. His speech, his gestures, his attitudes, his reasoning, everything about him surprises me, he isn’t like anyone else I know. During his years in hospital, he gradually cast off all his belongings. He had no proof of identity, no toothbrush, no coat, no wallet, no keys and no phone. When I asked him about work, about the question of choice, of decisions, any objects that, in his everyday life, could make sense , he can’t think of anything. After a while, he said to me: « I’ve thought of an object… my pipe… My pipe is my freedom ». For weeks, even though he only had 15 euros a month spending money, he saved a few euros whenever possible, until he managed to save 25 euros to buy this pipe. He likes it a lot, not only its shape, but also smoking a pipe rather than cigarettes. He finds it gives him a certain style. A pipe, or the possibility for him to envisage existing again.

#04 • STEPHANE’S COCKROACH TRAP •

It is months before Stéphane agrees to talk to me. One day, he let me visit him in his hotel room with one of the home’s caseworkers. Home visits are a means for the professionals to keep in touch with – and keep an eye on – those who have left the home. They consider the general condition of the lodging as an indicator as to the person’s state. Like Antoine, Stéphane pays 700 euros a month for a hotel room that is several square metres, with no toilet or shower, that I consider seedy, but that he wouldn’t leave for anything in the world. Madeleine, the caseworker who came with me that day, explained later that, for many patients, the family home is uninhabitable as it is too full of objects, memories, trauma sometimes, and that a furnished hotel, however seedy, is sometimes the only habitable place for them. Sometimes, those that hear voices at home, don’t hear them anymore in a more anonymous place. In a hotel, the walls don’t speak. In Stéphane’s bedroom, hundreds of CDs are piled up on a bedside table, cockroaches wander over the floor, the furniture, the walls and soon over our shoes. He put a trap in the corner, probably months ago. His notion of time passing, hygiene, cleanliness, is not the same as mine. But it’s nothing, after all, that puts him in danger, or anyone else, so nothing that involves forcing him to do anything about it. This trap, with its trace of time passing , which doesn’t pass at the same speed as for everyone else, but which is also a possible sign for the professionals of a deviance from hygiene norms, interests me immediately. On my return from this visit, I go back and read the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen : « Liberty consists in the freedom of being able to do that which doesn’t hurt others ». So in a hotel where, in any case, cockroaches are rife, Stéphane more or less complies. When I bump into him a few days later, I ask him if he would let me photograph his roach trap. He refuses and talks last several weeks, until he comes to the home one day with a big smile on his face, carrying a plastic bag and telling me that he has brought what I wanted. When I come to photograph it, I realise that several generations of cockroaches have been born on this sticky sheet, and that, even though the mothers were all dead, the smallest ones could wander over the sheet without getting trapped.

#12 • SOULEYMANE’S RING •

I know Souleymane from the home, but also from outside it. He lives in the neighbourhood of my hotel , volunteers in various associations that I help out with and so we bump into each other from time to time outside my work. At the home one day, he tells me that he has met a woman, that he is in love with her, and that he wants to buy her an engagement ring. The ring costs 150 euros. He is under guardianship, and is allowed a budget of 60 euros a week, which is roughly the same for all residents that I know. They have about 1000 euros in monthly income between the Handicap Allowance and rent benefit, 750 euros of fixed costs, therefore 250 euros left over for everyday spending. Souleymane has a few savings in his account and must ask for exceptional permission from his guardian. A discussion involving several people follows in which each person’s concept of what is normal comes into play, to see whether it is reasonable to buy an engagement ring for a woman that you have only known for a month. For Souleymane’s sister, it’s too soon : he should wait several more months. For Julien, a caseworker at the home, an engagement ring is « at the end of a year ». For Louise, a psychiatric nurse, it should « under no circumstances be sooner than 6 months ». For the guardian, it depends mainly on the state of Souleymane’s bank account, but not only. Finally, he manages to convince everyone and his guardian frees up the sum from his account. He buys the ring the next day and brings it to me so I can photograph it. During the shoot, after having spoken to me about his fiancée for a quite a long time, I naively ask him what she does for a living : « I don’t know, I’ve never asked her… she is a researcher, I think… or a waitress, I can’t remember ».

#13 • MAUD’S HAIR •

Several months after I arrived in the home, Benjamin, a friend of mine, tells me a childhood memory that had made its mark on him. One evening, the emergency services came to his house to take away a friend of his parents that he had known forever. She was naked and screaming. They grabbed her arms and legs, carried her like an animal while she struggled. I asked Benjamin if I could meet her, he gave me her number and I called her a few days later. Maud has lived in the Cevennes for several years, and so I can’t meet her but she agrees to answer my questions by phone. She is in her 40s, worked in graphic novels for many years, and speaks to me about her childhood as being a very difficult period, during which she developed a permanent feeling of having been abandoned. She would have liked to have been loved more. When she was in her 30s she had her first crisis following a whole mess of family, emotional and professional problems. Nine others followed, which mainly ended in forced hospital stays. The first time, she started systematically and meticulously throwing away all her belongings. She lived in Angouleme at the time, and so as not to arouse the suspicions of her neighbours, she took a binbag full of things down every morning : her photos, notebooks, books, her hi-fi, her discs, her love letters. After several weeks, her apartment was empty. The only things left were her bed, a chair and some peaches. She only ate peaches. It was at the end of this period, when she had thrown everything away she owned, that she ended up throwing away her only dress. She went out naked onto the streets at dusk, and ended up at Benjamin’s parents, who called the emergency services in the middle of the evening. Several years later, when the blank canvas she had made of her life led her to move to a small village house in the Cevennes, she had another crisis. She started systematically throwing everything out then ended up leaving at night, naked once more. She was taken in by a friend that I was to meet later, who told me that he had done everything possible to avoid a forced hospital stay. At the time, he managed to convince her to go with him to a hospital, to speak to a pyschiatrist that she knew and had been seeing. But the mission failed, they set off on the road again and she leapt out of the car in the middle of the night on a mountain road. The following day she managed to convice the hairdresser of the nearest village to shave her head. Her hair was the last thing she could get rid of. With a bald head, symbolically ridding herself of the ultimate attribute it is taboo to lose, her femininity, she crossed a line. The line of the women whose heads were shaved as collaborators, of those that returned from extermination camps, of mad women in the Middle Ages, of daughters of those executed by firing squads during the Spanish Civil War. The image she projected became intolerable, the authorities were informed, and the emergency services finally picked her up. She spent two weeks in solitary confinement, « tied up like a pig », as she likes to say… One day I received this strand of hair in the mail that she was kind enough to send to tell her story.

#24 • THE BENT FORK •

I spend several days in a private psychiatric clinic. One morning I went into a patient’s room with one of the research team. On entering the room, I quickly saw a bent fork, which reminded me of the other everyday objects that I had already photographed, the toothbrush, the knife, and which, because we aren’t used to seeing them bent, immediately affect us. My colleague looked at me and smiled : we have here the “object of a madman”, that’s for sure… On first sight, this bent fork is comforting, it looks like the concrete proof that the person before our eyes is definitely mad, or broken, that there has been no mistake. But rapidly the trap of appearances closes round us : an auxiliary nurse satisfies our curiosity by explaining that the man bent his fork, not because he was delirious, persecuted or suicidal, but simply to press the tobacco down in his pipe. His pipe tamper had been confiscated when he arrived in the clinic, and he had had to make do. It was just a makeshift object, of the same kind that prisoners use to make heaters, pans, radio aerials, to survive basically in an institution . This fork coldy reminds us of the constant risk for the person described as mad of seeing his words and deeds – particularly the most rational – used against him as new proof of his madness.

#31 • SOPHIE’S GLASS OF ALIGOTE •

When talking about my photographs of objects, a friend of mine, Sophie, told me one of the first memories of her father. She knows from her mother that, after 3 years of hiding the fact that he was Jewish in occupied Paris, he was automatically interned in 1947 by the special police detention centre, diagnosed as paranoid and treated with electroshock therapy. Sophie can remember his visits to Burgundy in the 60s when she was little and he lived far away from her, and his eccentricities which were sometimes worrying. For her 8th birthday he had invited her to a restaurant in Châtillon-sur-Seine, after a ride in his blue Mustang that he drove on the left-hand side of the small roads – “that’s how they drive in Great Britain my little darling”. She was a bit frightened. He had ordered a bottle of white Burgundy, Aligoté, for her and a bottle of Coke for himself. He didn’t care, she smiled, almost amused. Then he let the waiter serve her a glass and when she said, ‘no Dad, I won’t drink it’, he took her glass and threw the wine into a flower pot. That was what she hadn’t been able to stand. She thought, and still thinks, that it would kill the plant. For the whole time he was alive, she was scared that he would hurt others, she felt responsible for any eventual consequences of his acts.

#32 • SIMON’S BEACHBALL •

Alice runs a medico educational institute, which specialises in autistic and polyhandicapped children. She told me about Simon, “a gentle autist, cuddly and a dwarf”. He has been living in the institute since he was 7, he is now 25. Until a 1989 French law amendment, people in his situation left the institute either for another institution for adults – when there was room, or went home to live with their parents full-time. Nowadays they remain in establishments for children until they get a place in an adult service. Every Monday morning, after the weekend, Simon’s mother arrives with a small, white plastic bag. She opens it and shows the team a nappy full of excrement, in the midst of which she points out various objects that Simon has swallowed at the institute. She uses a tongue depresser to find the objects and asks the team to come closer to see for themselves. That Monday, in the middle of the excremement, she shows them a beachball that is roughly 20cms in diameter, faded and intact, that Simon has swallowed whole, nozzle and all. She cries in front of the team. This ritual has been going on for years, and everyone dreads being on call on Monday morning. Simon has had several hospital stays for intestinal occlusion, and her mother is terrified. She joins the parents association, is elected to the council for social life and onto the board of directors to make things change. Alice explains to me that Simon swallows everything he can find : he dismantles wheelchairs and swallows the bolts, eats light bulbs, door screws, latex gloves, bowls that he breaks, plastic spoons, tubes of paint. The team is constantly worried as they know that Simon is potentially always in danger. But Alice doesn’t have the means to put an employee on full-time watch, so she has tried to make an adapted space for him. The building is square, the courtyard in the middle has been transformed into a covered patio, and she has removed everything that could be swallowed, which lessens the risk for Simon, but means the other residents lose out. The only objects remaining in the space are ones that the team has noticed Simon never eats : cast iron chairs – “he doesn’t eat the soldering”, a plastic mattress, tables without bolts. The auxiliary nurses from the team keep hidden the most spectacular objects that Simon has swallowed, they disinfect and stock them, they have become their “trophies”.

#36 • EGLANTINE’S KEY •

In the Bénard Pavilion, a closed psychiatric service in one of the hospitals near Marseille, the patients’ rooms are on the 7th floor of the building, and I am surprised on my first visit by the height of the glass protection walls around the terraces. They are 6 or 7 metres high and the last section leans inwards to complicate any escape attempt. The head nurse of the service tells me that a few years ago, a patient jumped over the old glass walls and that they had had to make them higher. A few months later, I spoke about this to Eglantine, a nurse who has been with the unit for 20 years. The patient in question was well-known in the service, had spent several periods of time there, and all the auxiliaries got on well with him. When he came in that day in hand cuffs, for a forced hospital stay, instead of frisking him immediately and taking everything from him, Eglantine let him have a few minutes peace in his room, “to rest”. That evening, when he was found on the pavement 5 stories below, they found the key to his flat in his trouser pocket. The key should have been taken from him as soon as he got there, according to procedure. He had probably hidden it in the ceiling panels during the few minutes rest that Eglantine had given him. And she has never stopped saying since that if she had frisked him straight away, he wouldn’t have kept the key, and he wouldn’t have jumped. A month before, the service had moved from the 1st to the 7th floor, and the patient probably didn’t realise that by jumping, his escape attempt would become a suicide attempt.

EXHIBITION

In part of Mois de la Photo 2014

Objets sous contrainte

Photographs by Jean-Robert Dantou

Curated by Christian Caujolle

Search by Florence Weber, avec Solène Billaud, Pauline Blum, Julien Bourdais, Baptiste Brossard, Gaëlle Giordano, Hervé Heinry, Julie Minoc, Samuel Neuberg, William Vega, Jingyue Xing

From Novembre 13 to Decembre 13, 2014

Vernissage le samedi 22 novembre à partir de 14h

ENS – Ecole normale supérieure

45, rue d’Ulm

75005 Paris

France