After Clément Cogitore, LE BAL presents the first monographic exhibition devoted to Yasmina Benabderrahmane (1983), winner of the LE BAL Award for Young Creation with Adagp and a young artist graduated from the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris and from the National Studio of Contemporary Arts Le Fresnoy.

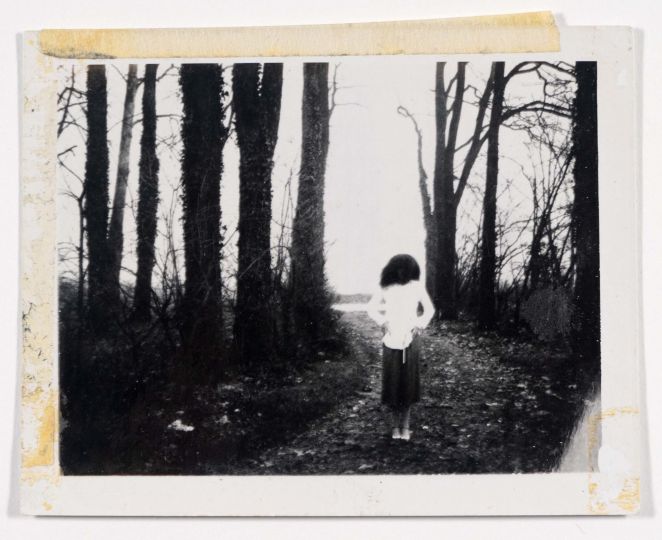

Returning to Morocco after 14 years of absence, Yasmina Benabderrahmane delivers with the Beast a filmic tale, between metaphor and rough fragments, marked by two characters from her family : Her uncle who is a geologist, responsible for “the Beast”, pharaonic work site of the new Grand Theater of the Bouregreg valley, and her Grandmother, a little further, in an ancestral village of the Atlas.

In the jerky jolts of film, her work invites us to a sensitive, mineral and instinctive stroll where the fate of contemporary Morocco is played out.

Interview between Yasmina Benabderrahmane and Adrien Genoudet

A.G. You returned to Morocco for the first time in 2012, after fourteen years of absence. This work is the fruit of several journeys, and your images draw, in a sense, a cartography that is both real and intimate. On the one hand, they present characters, who are members of your family, and on the other, specific places, with which you have a particular bond. Can you go back to your arrival in Morocco and the discovery of the Grand Theater, of “the Beast”?

Y.B. At first, we wandered, with my uncle and his wife, in the region of Rabat. One day, they showed me the site of a huge project, the Grand Théâtre, which was to be built in the Bouregreg valley. It is a valley known as the Valley of the potters, deemed inconstructible, because the marshes make the soil loose, unstable, not conducive to the construction of buildings. We still felt the trace of men who came to take clay from the valley to make pottery, tagine dishes and other ornaments. It was beautiful, touching, and it seemed unlikely to me that something could be built there. My uncle is a geologist and work for the state, his research laboratory, was responsible for assessing the terrain and conceptualising the solidification of the soil while respecting the territory. You can’t settle like that, because the earth lives. So they brought in a rock from the Middle East to harden this loose material and create a new ground in which water could still pass and infiltrate. I found this story quite incredible. I did not understand until later that this project of the Grand Théâtre had been decided by the King himself. He had asked Zaha Hadid to design the architecture and she had accepted. The construction site started in 2014 and unfortunately she died during construction in 2016.

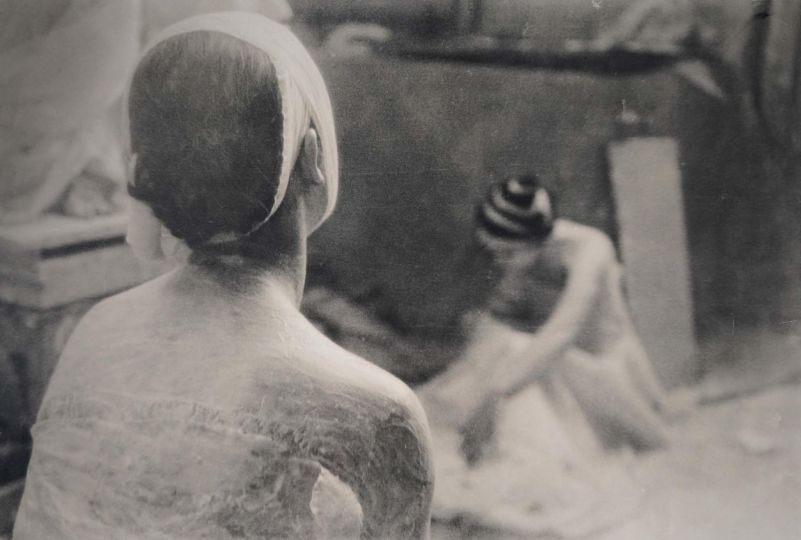

I also remember, in the early days, the silence. When I visited the site, at the beginning, everything was calm. I went there during break times or during Ramadan, people were not working, they were eating or praying. Around the site, we could see vast flat and bare land, recent roads, very empty, immense, rocky areas. A desert that gradually emerged from nowhere, since it was not a desert before. Mountains gradually appeared, increasingly large, pyramidal, enormous. Everything was very dry, powdery, without water. The whole lacked life because the animals had left to live elsewhere. Everything seemed a little strange and my first films tried to account for this strangeness, these non-zones, things that flew, dust, silence.

A.G. So there is, at first, thanks to your uncle, the discovery of this valley marked by a pharaonic construction site, then the reunion with your family, in an isolated village of the Atlas, place where your grandmother was born and where she lived. She has become, moreover, one of the central characters of your work.

Y.B. We hadn’t been together in Morocco since I was 5 years old. We went to Chichaoua, near her home village, in the house of her older sister who is 96 years old. We arrived at the time of Eid.

A.G. So, very quickly, did you start taking pictures?

Y.B. Yes, very quickly. In 2012, I rediscovered a country that I had completely forgotten, which had completely changed. Even my family members, I did not recognize them. You don’t see anyone growing up, that’s the most terrible thing. So I started filming everything, wanting to crystallize everything. It also helps me to see through a filter, a screen, a building of glass. These images are part of my story, that of my family. Looking at them, you can see that my grandmother lived simply, in connection with tradition. Having been raised by my grandmother, this bond meant a lot to me, even if we lived in France and not in the country where she was born and raised.

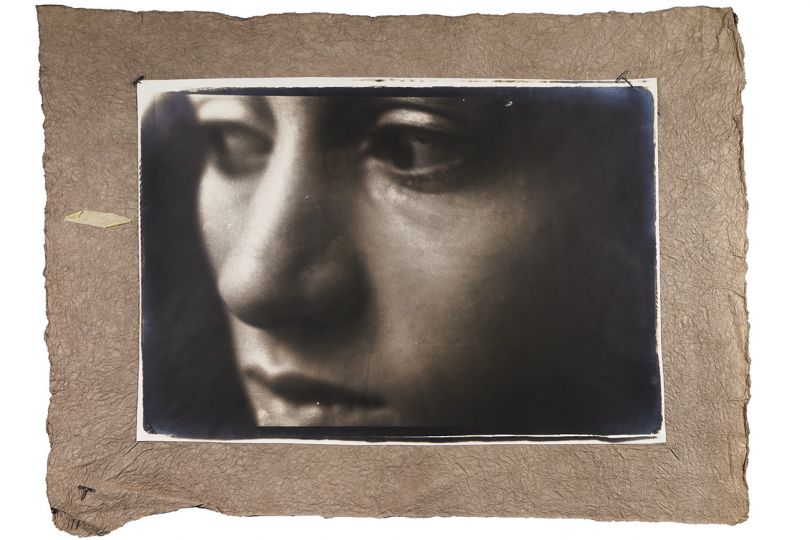

A.G. The character of your grandmother, as you film her, is also a metaphorical character. She embodies, through her gestures, her words, she is the embodiment and the witness of tradition. How has she established herself as a central “figure” in your work?

Y.B. My grandmother once said to me, “You can’t force anyone to be filmed or to pose for you. But, me, film me, I have nothing to lose. I am old. “My grandmother is a very pious person who has a very modest relationship to the body. The only parts of her body that can be seen are her feet and hands. I started filming her in her daily life.

A.G. If they are in a sense opposite in their links with contemporary Morocco, your uncle and your grandmother are not antithetical, opposite or inverse figures – they meet in fact in the images that you took during the Eid festival. Are they for you two figures, two metaphors of the different temporalities of Morocco?

Y.B. It remains, above all, the relationship between a mother and her child. I think of these two characters as a pair, one cannot exist without the other. When I talk about this great project, I often speak of deus ex machina, because all these upheavals in the landscape project us into an improbable, fantasized future. What interests me all the more in the construction of a theater is to see there, with all its entrances and exits, stage right and stage left, a bit like a large continuous stage where life would be played out and infra-life. I imagine thousands of ants building, on an immense waste heap, a disproportionate work, out of scale, imagined by the King. The work of the body, on a site like this, remains, not inhuman, but on the verge of the superhuman. Even if the machine is there, most of the work is done by the workers, their bodies and their tiny gestures put end to end. And it is the same, in my opinion, for ancestral rites. During the traditional Eid festival, I filmed my grandmother and uncle “sacrificing” a beast – a sacred beast.They both, repeat every year the same gestures, precise and ancestral, those of the Prophet. This ritual of sacrifice is rooted in the lives of my family members. It’s a moment of sharing. And this beast is nourishing, and every thing is used down to the last shred.

A.G. Your work is crossed, from start to finish, by the double presence of the “Beast”: both the Beast as a mechanical, modern and devouring site, and the traditional beast, the sheep, which is sacrificed generation after generation to perpetuate the rite …

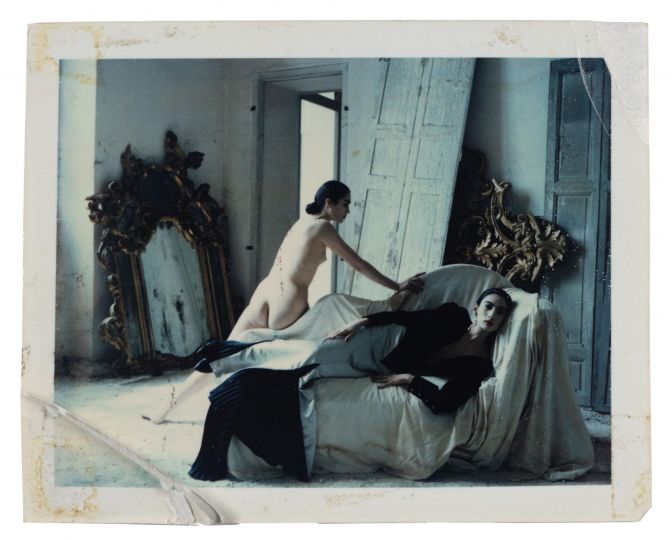

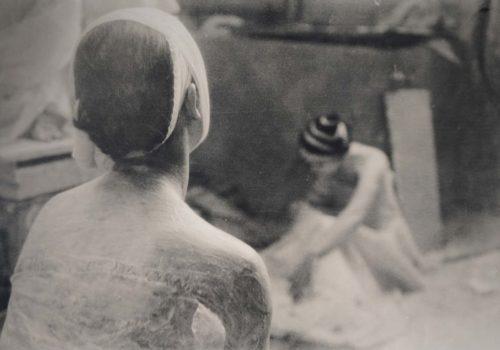

Y.B. The whole project is marked, from the beginning, by this viscous matter, by this presence of the flesh and, little by little, visual links will be established with the textures of the site, the pouring of the concrete, the molten bitumen, the carapace of the frame … A moment saw the real junction of these elements. In 2016, the site was paralyzed following the sudden death of the architect. To “ward off fate”, the authorities sacrificed a hundred white sheep and calves at the work site. We make blood flow to purify, unlike water, which is there to fertilize. This symbolism of fluids inspired me a lot. This link to the sacred pleases me, I grew up in a very pious family where it naturally took place in everyday gestures, the memory of bodies. I chose to show it in fragments to give it a general, almost universal scope.

A.G. When you see the situation of contemporary Morocco, don’t you want to take your camera, to film, to document this reality?

Y.B. No, it seems too hard, too difficult. I am shocked, paralyzed, even attacked. And there is the language barrier. I don’t understand literary Arabic. So, here I am, I receive, I assimilate. I am in the perceptible, I look for what, in reality, settles in me over time. I am not in direct cinema. Otherwise, I would have been a journalist or an anthropologist. Facing the world with metaphors is my way of resisting. I start with my family or intimate circle, because confronting myself immediately with a larger dimension does not suit me. Everything, for me, happens on this scale. I operate a form of transposition, from the cell to the whole.

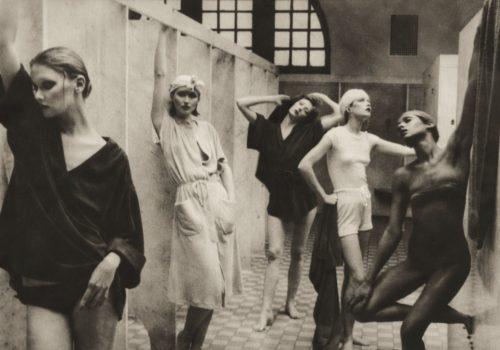

A.G. How do you explain your choice to sometimes use color or black and white? Do they have a symbolic dimension for you?

Y.B. Turning in black and white allows me to create a link with the drawing by the grain while having a sculptural rendering. We are in a “neutral” temporal value, which gives an archive dimension to the images. For some, I don’t want them to clearly mark yesterday, today or tomorrow. I like what creates trouble. In Godard’s Operation Beton, filmed in 1953, there are plans almost similar to those I filmed on the construction site. We find the same machines, the same types of conveyor belts, mechanical processes … I like the fact that the spectator wonders, that he/she wonders if these images of the Grand Theater really belong to the contemporary regime of representation of an architectural utopia. The image, for me, like reality, must remain an enigma. A non-trivial enigma.

La Bête, un conte moderne de Yasmina Benabderrahmane

January 15 – April 12, 2020

LE BAL

6, Impasse de la Défense

75018 Paris