This article by Claire Guillot appeared in Le Monde on September 16th, 2014. We would like to thank the editors of Le Monde and the author for allowing us to republish it here.

Iranian photographer Newsha Tavakolian claims that her report on her home country was misinterpreted.

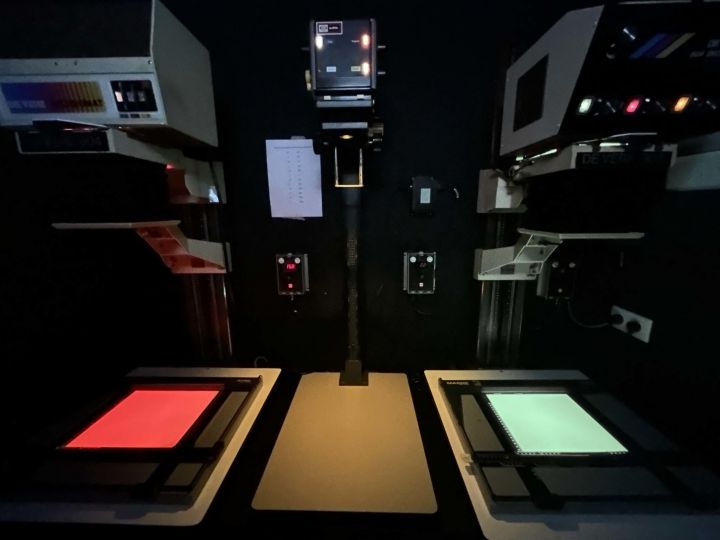

The Prix Carmignac photojournalism once seemed like a godsend. At a time when the world’s media outlets are cutting budgets, Edouard Carmignac, the management fund owner and millionaire art collector, has offered an annual 50,000€ prize to photographers to produce a long-term work of reportage, culminating in the publication of a book and exhibitions in several prestigious venues. The financier, known for airing his views in paid editorials in the French press, only intervened in the prize to choose the region where the report would be produced, leaving the choice of the winner to a jury of professionals.

Now, however, with the fifth edition of the prize, devoted to Iran and awarded to the photographer Newsha Tavakolian, 34, it turns out that this divine gift comes with more than a few strings attached. On Tuesday, September 9th, a phone call to reporters announced that the book and exhibition had been postponed due to, “pressure from Iranian authorities.”

Tavakolian responded with an outraged denial on her Facebook page, explaining that she would be returning the prize and money. “From the moment I delivered the work, Mr. Carmignac insisted on personally editing my photographs as well as altering the accompanying texts to the photographs. Mr Carmignac’s interference in the project culminated in choosing an entirely unacceptable title for my work that would undermine my project irredeemably. ”

Reached for comment in Iraq, where she is on assignment, Tavakolian added that the source of the censorship is not coming from Iran, but from France.

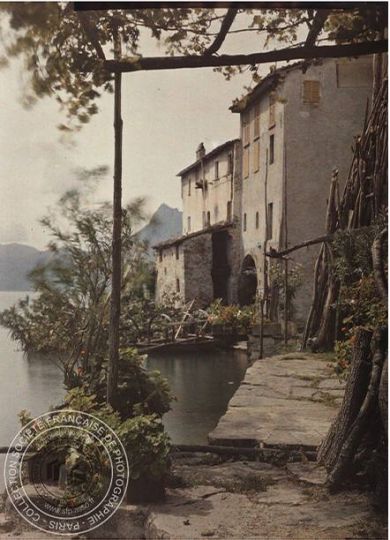

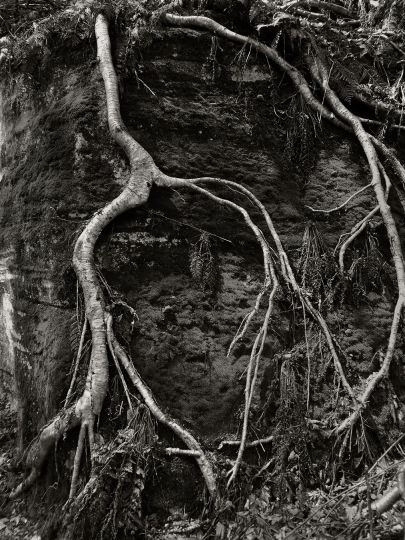

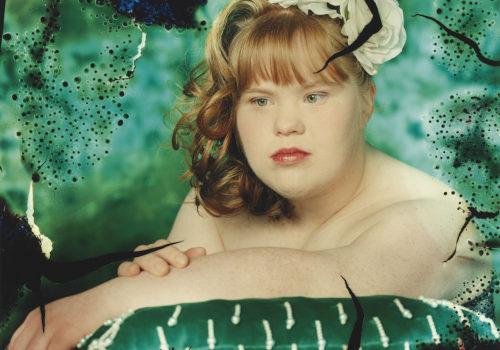

The Iran-based photographer chose to study young people aged 25 to 35, her own generation, whose parents participated in the revolution and who have struggled to make a future for themselves. Her work tells the story of nine men and women through candid and staged portraits.

Ms. Tavakolian states that prize director Nathalie Gallon has supported her project throughout the process. The latter’s voice is conspicuously absent from the discussion. Mr. Carmignac declined to answer our questions, but Emeric Glayse, Director of Communications, offered a new version of events: “The final project didn’t match the one she initially proposed. Ms. Tavakolian was supposed to work on the ‘burnt generation’ but focused instead on the middle class. She refused to budge.”

The jury which originally selected the project was never consulted in the decision. Its president, Anahita Ghabaian, a renowned Iranian gallerist, was beside herself. “To postpone the prize is to take us for a bunch of idiots. We might as well be extras,” she said by telephone from Tehran. “[Ms. Tavakolian] depicts the lives of people who have never known democracy, through portraits that are anything but innocuous: a veteran of the Iran-Iraq war who’s lost interest in life, a girl who grew up in a very religious family and who is now involved in a presidential campaign, and so on.”

What remains to be seen is if, and how, the next edition of the Prix Carmignac will play out. The topic is another sensitive subject: areas in France where law and order have broken down.

Claire Guillot

© Le Monde

Read the full article on the French version of The Eye