“The Neighbors,” an exhibition now at the Julie Saul Gallery in Chelsea, is, as you may have read, angering many residents of a certain TriBeCa building. Arne Svenson’s photographs, which he shot using a telephoto lens from inside his own apartment across the street, capture people at home through their windows. The neighbors, who were unaware they were being photographed, are somewhat obscured — bending over, back to the window, head turned, behind a curtain — and therefore mostly unidentifiable. But the subjects are recognizable to themselves, and maybe others.

One question being asked of the pictures is: are they art or an invasion of privacy? (And if they’re both, does the former justify the latter?) These particular pictures are problematic, even for those, like me, who overwhelmingly side with artists and journalists when it comes to questions of freedom of expression. I support the artist’s right to make and exhibit his art and feel Svenson has the right to exhibit these pictures. But if images surfaced in a gallery of my daughter in our home, shot by a photographer using a long lens without our knowledge, I wouldn’t be happy. So the question arises, is it art when it’s a photograph of someone else, but not when it’s you or your family? Or, could you argue that by choosing to live in the Zinc Building (which you can visit via Google Street View, a structure featuring floor-to-ceiling glass windows, Svenson’s subjects must have realized that others would be able to easily gaze into their windows? Does the fact that a photographer can see something give him the right to photograph it? Even if that something is Inside someone’s home?

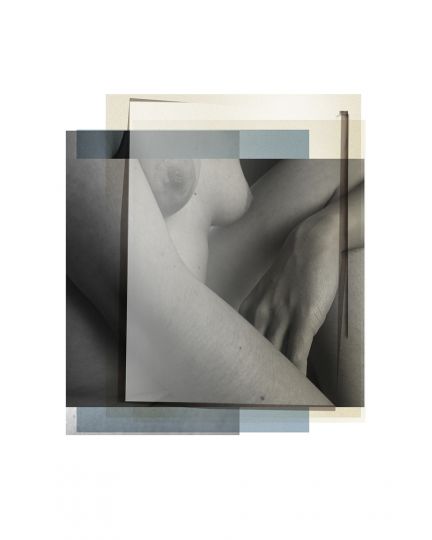

Svenson’s pictures are handsomely composed. There is a modern classicism to them. Incredibly ordinary moments are amplified and take on the kind of moody stillness seen in the work of Balthus and Edward Hopper. It also looks as if Svenson has taken care to err on the side of discretion by only exhibiting images in which his subjects’ identities are obscured. This gesture succeeds not only in protecting his neighbors’ privacy (somewhat), but also in strengthening the power of his art by rendering its subjects as more universal and appealing. But there is something deeply unsettling about the realization that someone has been watching you through your windows.

Questions of a subject’s right to his own image were at play when Erno Nussenzweig sued Philip-Lorca diCorcia and Pace/MacGill Gallery in 2005 after discovering that diCorcia had photographed Nussenzweig’s face in Times Square and had exhibited the picture at the gallery. Nussenzweig’s lawyer said that his client “lost control over his own image.” (Nussenzweig lost his case.) In 1978, a man sued The New York Times after a photograph of him, taken in public, appeared on the cover of this magazine without his consent. (He also lost his case). Both those situations should be seen as very different from the current one involving Svenson because the earlier photographs were made in very public places, on the streets of Manhattan.

I know I don’t speak for everyone, but for me, the freedoms enjoyed by artists and journalists are worth possible breaches of privacy. Otherwise we would most likely never get works of art like this video by James Nares, currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

What do you think? Do Svenson’s images constitute an invasion of privacy? If so, is that infringement defensible because they constitute art?

Kathy RYAN, Director of Photography of the New York Times Magazine.

This text has been published first on the New York Times‘s 6th Floor Blog. To react or comment the article of Kathy Ryan, click here.

EXHIBITION

ARNE SVENSON, The Neighbors

May 9 – June 29, 2013

Julie Saul Gallery

535 W 22nd St # 6F

New York, NY 10011

USA

(212) 627-2410