The American photographer Joseph Rodriguez (*1951, Brooklyn/USA) is a legend when it comes to street photography, particularly his arresting images of Latinx Communities in the United States, Mexico, and Puerto Rico.

Drawn to the social documentary style, he sought out photography in an attempt to challenge stereotypes and expose the world to truthful portraits of American struggle. People are at the heart of his work, which often emerges after lengthy periods of time spent gaining the trust of his subjects. The results are raw and gritty images that are full of life, revealing the resilience and beauty of the people he portrays.

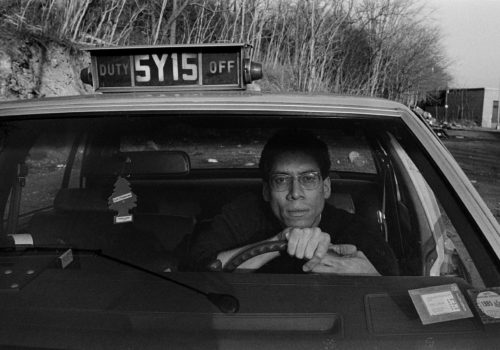

While he officially started taking pictures in the 1980s, his legendary series TAXI. Journey Through My Windows: 1977–1987 marks the very beginning of his photographic career. In these images he gives us slices of life in New York City, taken on the fly from behind the wheel of his cab, as a calm witness to a candid moment. This decade of images laid the groundwork for the insightful, humanistic style that brought Rodriguez widespread acclaim in the decades to come.

On the occasion of the recent publication of these photos as a monograph as well as his upcoming solo show of the same name at Galerie Bene Taschen in Cologne, we connected with Rodriguez to find out how everything came about, and what’s new.

Nadine Dinter: Your new book is called Taxi: Journey Through My Windows 1977–1987, and takes viewers on trips through New York, seen through your lens. How would you describe this period in your life in a nutshell?

Joseph Rodriguez: It was a time of transition. I was dreaming of becoming a photographer, so I began taking classes at the International Center of Photography in the mid-1980s.

What was it that sparked your decision to document life in New York while on the job as a taxi driver? Did you think about it from the start as a photographic project, or did it come together more casually?

JR: First, I wanted to document the New York City I grew up in, which I love, but I had many shadows to walk behind, of some of the greatest photographers from the New York school of photography, such as Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Alexey Brodovitch, Ted Croner, Bruce Davidson, Don Donaghy, Louis Faurer, Robert Frank, Sid Grossman, William Klein, Saul Leiter, Leon Levinstein, Helen Levitt, Lisette Model, David Vestal, et Weegee, Ian Conner, Morris Engel, Harold Feinstein, Ernst Haas, Arthur Leipzig, Ruth Orkin, Walter Rosenblum, Louis Stettner, Garry Winogrand, et Max Yavno.

While I was studying, I needed to work, and I had limited time to photograph, so I chose to shoot my working as a cab driver.

Capturing those slices of life in your photographs, you must have had your camera by your side the entire time. Were you worried about it being stolen?

JR: No, I didn’t think too much about being robbed.

The decade in which you took these photographs saw some of the city’s highest violent crime rates. How did you cope with the atmosphere of violence and fear, throughout the day and years you worked one of the most dangerous jobs at the time?

JR: You just lived through the times, just like now with us living with Covid-19: these are stressful times today, and crime is also gone up.

What was your relationship like with your fellow taxi drivers? Did you have friends among them, with whom you shared personal or job experiences, or was it more anonymous?

JR: I met my fellow cab drivers at the garage before and after our shifts, but it was a tough job driving for 12 hours.

In your book you share anecdotes about your passengers. How do you remember them after all these years? Did you keep a written diary at the time, taking notes during or after your shifts, or did they just stick in your mind?

JR: Yes, I would keep a diary. I do this with every project I do.

What was your preferred hour to drive through New York, in search of new passengers, and why?

JR: That would depend, on the weekends driving nights we had lots of night life in the city. Theater actors, bartenders, night clubs, discos. During the week my fares were mostly workers going to and from their jobs.

How did your approach to photography change after that decade of taking pictures from your cab?

JR: My approach taught me the art of listening which helped me to get closer to people to photograph them.

Richard Price, who wrote the preface of your book, stated, “In the end, it all comes down to this—that in order to be a great street photographer, you need to love the street.” Do you agree?

JR: Yes, I agree but also love what you are doing.

What did you especially love about the streets of New York back then, and what do you love most about them nowadays?

JR: Back then I loved the city and its people – there is a tough love that exists with us New Yorkers. Today, the city has changed with its wealth, architecture, and fancy restaurants, and people don’t talk to each other as much.

What’s your advice to the aspiring young generation of photographers who want to make it in the street photography business and also as a photojournalist?

JR: Don’t just shoot street photography, the internet is flooded with too many street images.

More on Joseph Rodriguez at http://www.josephrodriguezphotography.com/

Follow him on Instagram @rollie6x6

About the book:

Joseph Rodriguez, Taxi: Journey Through My Windows 1977–1987,

with an essay by Richard Price, New York: powerHouse Books, 2020, 132 pages, $35,

ISBN: 9781576879313

Exhibition:

“Joseph Rodriguez: TAXI” at Galerie Bene Taschen, Moltkestraße 81, 50674 Cologne

Opening: 4 & 5 June 2021 / Duration: through 24 July 2021