Louis Stettner was one of the most highly regarded street photographers of the 20th century. I discovered his work through my contact with Johanna Breede and her gallery some years ago. His calm yet intense photographs made a lasting impression on me.

One day, I received a call from his daughter Isobel Stettner, with whom I ended up chatting at some length. We stayed in touch, also about the major Louis Stettner retrospective that just opened at the MAPFRE Foundation in Madrid. Naturally, I wanted to know more about the man behind those iconic images. I had the pleasure of interviewing his widow Janet Iffland-Stettner about his career and what makes his photographs so special.

Warm thanks to Janet and Isobel for sharing their fantastic insight into Louis Stettner’s work!

Nadine Dinter: You are currently preparing a major retrospective of your husband’s work. Please tell us about what visitors can expect to see.

Janet Iffland-Stettner (JI-S): The Fundación MAPFRE in Madrid has organized the most comprehensive retrospective to date of Louis’s 70-year photographic legacy. The exhibition includes 190 photographs insightfully curated by Sally Martin Katz.

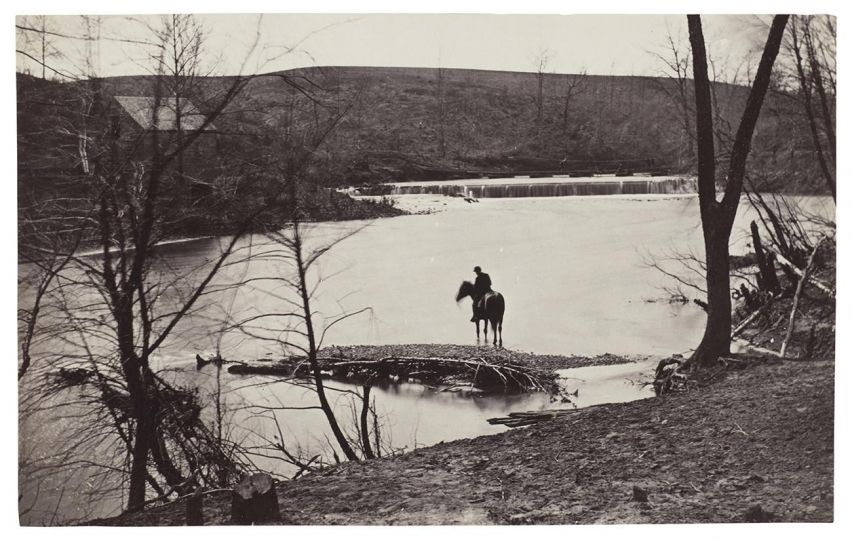

In her words, “The exhibition is organized chronologically and charts [Stettner’s] work from his early days in Paris, photographing the empty postwar city, and in New York, photographing commuters in the subway and at Penn Station, to his later use of color photography, and ends with his final meditations on the landscape of Les Alpilles in the south of France.” The exhibition also includes a video of Louis addressing his work and his relationship with Paris.

I would add that the black-and-white photographs in the exhibition were printed by Louis himself. Throughout his life, he held the deep-seated conviction that interpreting his negatives in the darkroom was a creative act inseparable from the act of taking the photographs. It was an integral facet of his photographic vision and his view of himself as a photographer.

Louis Stettner was part of the Photo League, worked alongside Weegee, learned from Brassaï, and became one of the most esteemed street photographers of his time. How does the exhibition reflect on that, and how far back does it start?

JI-S: The exhibition begins with two important early series. The first is the Subway Series from 1946, taken in New York during Louis’s close association with the Photo League, both as a member and then as the League’s youngest teacher. It cannot really be said that Louis “worked alongside Weegee.” However, it is true that having first met Weegee at the League and later taking care of him after he fell ill in Paris, they forged a 25-year friendship.

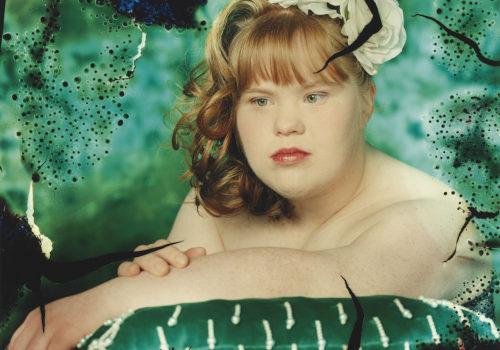

That said, the more prominent influence at the League was actually Sid Grossman, recognized as one of the greatest teachers of “documentary” photography. It was Grossman who wrote the first commentary on Louis’s first published photographs of the Subway Series. There Grossman noted Louis’s “fine feeling for the meanings in a face; his sensitivity for the revealing relationships of an angle of hand, a disheveled shirt, and a slightly curious stare on a tired face,” resulting “in specific creations which give us new insight into the meaning of these people’s lives.” (New Iconograph, Fall, 1947).

The exhibition then continues with a series of post-World War II photographs of Paris, taken between 1948 and 1949 with an antediluvian 20×25 cm army surplus field camera, and focuses on a stark environment bereft of people. It was during this time that Louis met Brassaï, whom he came to consider his maître. The exhibition continues to show photographs taken during Louis’s five-year stay in Paris until 1952.

On a personal note about Louis and the Photo League, I would like to add that the Photo League went on to be blacklisted and eventually ceased to exist after being labeled as a “subversive” organization by the US government. Louis lost his job as a photographer for the Marshall Plan because he refused to give up the names of communists in the League. He said that not only were his fellow Photo League members friends, but whatever political affiliation they might have was for them to divulge.

He went on to write, “What puzzled me was an unanswered question: Where was the freedom I fought so hard for as a combat photographer in World War II?” Despite this experience, Louis continued to create images, many found in this exhibition, that reveal his ongoing faith in his fellow human beings.

Brassaï once said about your husband: “He sees the photographer not only aware of the richness and beauty of the world but also responding to the diverse aspects of the society in which we live.” Do you agree, and what, in your eyes, was Stettner’s stylistic trademark?

JI-S: Throughout our long relationship, I came increasingly to appreciate Louis’s embrace of life in all its aspects: from the surfaces of things to the deep energies that move beneath. This appetite for life itself both drove his passion for the photographer’s art and rendered his oeuvre difficult to categorize.

David Campany offers the most articulate description of Louis’s particular genius that I have ever encountered, in an essay he wrote for the exhibition catalogue, entitled “To Value What is in Front of Us”:

The variety of his images was not the result of scattered imitation, either conscious or unconscious… Neither was it to do with a lack of artistic direction. No, I think the cause was Stettner’s capacious disposition towards the world, combined with a wide and generous sense of how that world as he experienced and understood it could become pictures… We get the impression he was a person of wide visual appetite, with great feeling for humans and their circumstances, and deep affection simply for the appearance of things – for the way they looked to his eye; for the way they looked in photographs. No singular vision imposed itself upon him as a unitary way of picturing. His images are always ‘strong,’ as they used to say, formally rigorous and resonant, but they resist overt signature style.

There are quite a few “power couples” in the art world, like Helmut and June Newton, Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, and Pierre et Gilles. Did you see yourselves like that? What was your role in the creative relationship?

JI-S: I can respond to that question with a resounding “No!” We did not see ourselves in those terms. That said, we did complement one another, and in a sense, the nature of our relationship continues to manifest itself to this day: for example, in the planning and realization of Louis’s exhibitions. I often found myself acting as a facilitator, even a mediator, between the artist and the people and institutions who held the power to bring his work to a wider public.

To explain more fully, it should come as no surprise that generational tensions arose between evolving market forces in the art world and Louis’s lived experiences during the period when many of his photographs were conceived: as a child of the Depression, a combat photographer in World War II, a witness of the destruction of Hiroshima, and a victim of McCarthyism as a result of his association with the Photo League.

Navigating these tensions frequently proved challenging for Louis. Complicating matters further were the nourishing relationships with the likes of Paul Strand, Brassaï, Weegee, Boubat, Faurer, Lisette Model, and a group of Scandinavian photographers including Rune Hassner and Tore Johnson, just to mention a few. He used to explain that it was his fellow photographers’ critiques of his work that were the most meaningful to him.

Finally, Louis’s early and ongoing study of the history of photography and his extensive writing on the subject helped to clarify and solidify his approach to his own creative endeavors. With empathy and affection for both Louis’s particular genius and those whose passion it is to nourish the wider world of the photographers’ art, I found myself uniquely suited to the role I continue to play.

Talking about roles: managing the Louis Stettner Estate seems to have become a family business. Would you like to share some further insight on your work with the estate?

JI-S: I would like to think of it as something other than a “family business” since that term denotes a primarily commercial enterprise. Nevertheless, it is definitely a family affair! Complicating matters is the fact that some family members live in Europe, and others live in the United States. The archives themselves find a home near Paris. Thus the functioning of the estate has an international dimension perhaps not encountered by most estates.

As you are doubtless aware, maintaining and promoting an artist’s legacy requires the work of many hands. A natural division of labor arises that includes working with institutions and galleries, maintaining a presence on social media, preserving the archives, and organizing them in an accessible condition. As there are five family members with varying demands on our time and effort, responsibilities in each of these areas may be fluid.

As head of the estate, my role is primarily to work with institutions, educate the public, and maintain the archives. Isobel Stettner-Hoevers manages interest in Louis’s work in the United States, where she lives, as well as maintaining the estate Instagram account.

The goal of all these efforts may be summarized in a mission statement I wrote to introduce a new website we have recently launched:

The Louis Stettner Estate is dedicated to the preservation and advancement of the seventy-year creative legacy of Louis Stettner. The Estate maintains the photographic archives, painting and sculpture works, writings, and personal papers concerning his life in photography. The Estate also works toward serving as a comprehensive resource regarding the artist and his life’s work, while remaining ever mindful of his credo:

My way of life, my very being, is based on images capable of engraving themselves indelibly in our inner soul’s eye.

Also, through my personal vision, to reveal what cannot be readily seen, to capture what is most meaningful, to enrich our appreciation of life.

It is to explore and celebrate the human condition and the world around us, nature and man together, to find significance in suffering and all that is profound, beautiful and nourishes the soul.

Above all, I believe in creative work through struggle to increase human wisdom and happiness.

Returning to the upcoming MAPFRE show: Will there be any unknown or unpublished works on view? How much time went into preparing this retrospective?

JI-S: Yes, there are a number of unpublished images exhibited. They include New York pre-World War II photographs from Louis’s earliest years and a group of protest images from the boycott movement supporting the work of Cesar Chavez and the unionization of farm labor in the 1970s. The last sections of the exhibition reveal for the first time both the rare color photographs taken between 2004 and 2011 in a series titled Manhattan Pastorale and the little-known Alpilles Series, the black-and-white large-format photographs taken in the Alpilles of Provence, France, between 2013 and 2016. I was particularly heartened by the inclusion of these two little-known series as it permits this exhibit to be the most extensive exploration of Louis’s life’s work to date.

The genesis of the exhibition dates to 2018 at the opening of Louis’s exhibition at the SFMoMA, Traveling Light, where Clément Chéroux introduced me to Carlos Gollonet Carnicero of the Fundación MAPFRE. Roughly two years ago, after delays caused by the Covid pandemic, Sally Martin Katz, with whom I had previously collaborated in her position as Assistant Curator of Photography at the SFMoMA, was chosen as the curator for the exhibition. This was extremely useful, as Sally had already acquired a deep appreciation and understanding of Louis’s work.

Since then, the most comprehensive catalog ever of Louis’s photographs has been produced and includes all the images in the exhibition, accompanied by four wide-ranging insightful essays. Over the last year, the intensity of work accelerated thanks to the extraordinary professional team at Fundación MAPFRE, whom I quite honestly hold in the highest esteem. Their unflagging dedication to the exhibit is a living testimony to the legacy of Louis’s work and the principles by which he chose to live and Fundación MAPFRE’s remarkable ethical commitment to society.

Which city most influenced Stettner’s work: New York or Paris?

JI-S: Perhaps the most articulate response to your question may be found in Louis’s own words:

“New York and Paris have been two spiritual mothers to me. The former causes the human spirit to soar through adversity, the latter through love. Perhaps both are necessary in life.

New York City is where I have lived for most my life, amidst the smoke, fumes, the bustle and the still moments or stray corners that have sometimes touched eternity. It has shaped and formed me and I in turn have constantly sought to come to grips with its significance as a place and above all, with the people that live in it. My photographs are acts of eloquent homage and deep remorse about the city. I am profoundly moved by its lyric beauty and horrified by its cruelty and suffering.

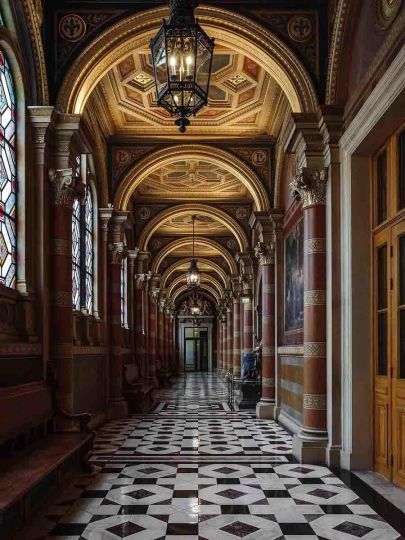

Paris is also a city which in many ways is an outdoor museum where you do not so much look at but experience art. Walking through a thousand years of architectural styles has influenced and inspired my photographic work. Its rich diversity has come about through a ceaseless experimentation that has encouraged me to search in my own art.

Yes, New York and Paris have been the two big cities that have shaped my life’s work. Brassai put it poetically, ‘Stettner is irremediably a city dweller. He finds his true element in the Capernaum of the big city, where all is art, artifice and intelligence, sweat and secretion of man.’”

What is your all-time favorite photograph of your husband, and why?

JI-S: My all-time favorite is the photograph, Les Alpilles No. 27, which Louis took in Provence during a three-year period of intensive creativity and during which we closely collaborated. Viewers will find this photograph in the last section of the MAPFRE exhibition, or as the last image among the photographs accompanying this interview.

Why this photograph? Because to me, very personally, it speaks to all that was Louis and our life together. He, simply, was a force of nature. The very stillness of the grasses captured in exquisite detail by an 8×10 field camera, while in the far background, the wistful movement by the mistral-blown trees, takes on an almost spiritual resonance. In essence, it speaks to me of who he was: a perceptive observer of the exquisitely still moments in life that pass most of us by, those that “touch eternity,” as he used to say… all the while embracing the very transitory nature of this life. There is a verse from the poet Walt Whitman that most intimately expresses my feelings about this photograph and particularly this last series Louis photographed: “We were together. I forget the rest.”

What is your advice for the new generation of documentary photographers?

JI-S: Here I will once again rely on Louis’s words, spoken in a film clip titled Message to Young Artists:

“It is really very simple. You either follow the bourgeois god, that money is everything,

or life is everything.”

The Retrospective “Louis Stettner” is on view at Fundación MAPFRE Recoletos Hall, Madrid/Spain.

Duration: 30 May – 27 August 2023

For more information, check out www.louisstettner.com and the estate´s IG account @louisstettnerestate