This month, it was my pleasure to interview the German-American collector Artur Walther, a true powerhouse in the fields of photography and art. For some time I’ve been following the activities and exhibitions of the recipient of the 2021 Culture Award of the German Photographic Society (DGPh Kulturpreis) and was thrilled to have this opportunity to chat with him about what’s new.

Nadine Dinter: Mr. Walther, you were just awarded the Kulturpreis 2021 by the German Society for Photography (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Photographie). Congratulations! What does this prize mean to you?

Artur Walther: Thank you. It was very humbling to be the recipient of the DGPh Culture Prize, which in the past has been awarded to many people I admire greatly. After living in the United States for more than 40 years, it was a special honor to have received this prize in the country I was born and grew up in. It is particularly touching to receive the award in Düsseldorf, which is closely linked to my original interest in photography, and connection with the influential artist duo Bernd and Hilla Becher. But as I said in my acceptance speech, I feel I am just the physical recipient of the prize; the honor is shared with all the curators, scholars, and the entire team working tirelessly with me on the Collection’s activities. The prize is also for all the artists whose work we have collected and exhibited over the years: it is a recognition of the outstanding works created in different cultures that were largely neglected until the last two decades.

Let’s jump back in time. When did you acquire your first photograph, and who was it by? When did you realize or decide that you wanted to build up such an impressive photography collection and devote your time to growing it?

AW: I spent much of my professional career on Wall Street in international investment banking. Although I found the field very exciting and challenging, it was also parochial at the same time. So I decided to pursue a more varied life — to travel, to study architecture and design, and to be more involved in the arts. This journey began at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York, where I attended numerous courses as an adult student. I took workshops with great photographers such as Joel Meyerowitz, Mary Ellen Mark, Bruce Davidson, Stephen Shore, and connected with the Bechers. Although I only made photographs for a relatively short period myself, the medium had a strong impact on me. I became a trustee at ICP and had joined the Photography Committee of the Whitney Museum. I realized I wanted to engage in different ways, and became very interested in all aspects of researching, collecting, curating, exhibiting and publishing. Over time, this new kind of engagement led to an increasing interest in building a collection.

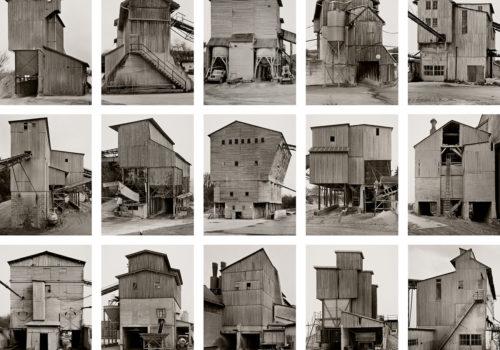

My first purchase was a typology of grain elevators from the American Midwest, followed by a series of iconic black and white photographs of coal bunkers, gas tanks, and blast furnaces by Bernd and Hilla Becher. They influenced me greatly; it was the beginning of a long-term friendship. Their investigation of industrial typologies closely reflected my own way of seeing and looking at the world… just last month, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York opened the beautifully executed retrospective exhibition Bernd & Hilla Becher which features a key work from the Collection.

Some of Germany’s most iconic images form the backbone of your collection: works from the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) and Bauhaus movements and photographers like August Sander and Karl Blossfeldt. And you recently started focused on African and Asian photography as well. What motivated you to develop the collection in this direction?

AW: There was no grand plan or specific thematic direction with my initial collecting. It developed gradually, starting with the Bechers and the work of their students, and later expanded with works by August Sander and Karl Blossfeldt, among other European and American photographers. Moving beyond Neue Sachlichkeit, I started to focus on artists who brought new perspectives and narratives that challenged the Western canon. It became increasingly important for me as I continued to develop the Collection further to broaden my knowledge through learning more about the work of contemporary artists from different cultural backgrounds, and the social, personal, and political environments they were operating within – and to see where there might be similarities between them, and existing works in the Collection: thematically, conceptually, aesthetically, et cetera.

I have been interested in photography and lens-based media art from China and Japan since the mid 1990s. The history of Chinese photography is extensive, and fascinating: the end of the Cultural Revolution and the economic opening of China under Deng Xiaoping ushered in the beginnings of a new creative freedom, providing a generation of artists with opportunities for exposure, mobility, and engagement beyond the country’s geographical borders. The critical mass of contemporary artists active in the 1980s and 90s represented an important turning point – it was this very moment that marked my first encounter with China, while a dramatic shift in artistic production was taking place.

I first encountered African photography in 1996, in the exhibition In/sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present at the Guggenheim Museum. The images of David Goldblatt, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Seydou Keïta, and Malick Sidibé affected me profoundly. They were so different from the dominant representations of Africa—the documentary and photojournalist images of war and famine, displacement, and genocide. I soon became close friends with the brilliant curator Okwui Enwezor, who was responsible for the show. In 2004, we began to research contemporary positions from Africa, with the idea to devote an exhibition to the theme. Okwui and I traveled throughout the continent for four weeks: from Tangier to Cape Town via Dakar and back to Cairo via Nairobi and Addis Ababa. The result was the exhibition Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, which opened at ICP in 2006 and was subsequently shown in Europe. This research trip, and the two exhibitions, drew my attention to African photography, which over the next 15 years would become the corner stone of The Walther Collection.

In recent years, the Collection has also focused on vernacular photography in a range of stylistic forms, archival applications, and physical formats—in particular, an in-depth exploration of the serial and multi-faceted nature of vernacular photography. Some of the broad categories represented within the Collection include family photography and snapshots, albums and photo books, ethnographic and scientific photography, mug shots and identification photographs, studio and street portraiture, as well as architectural, and industrial photography. We also hold several moving image, video and mixed media installation works.

How do you grow your collection? Do you research exciting new artists yourself, or do you have an art consultant to support you in new acquisitions, and which are your favorite galleries to work with?

AW: I have been very fortunate to surround myself with a brilliant constituency of writers, curators, artists, and academics, all of whom continue to deeply influence my way of thinking about photography while also introducing me to new developments and artists. When I collect artists’ work, I tend to collect in-depth — I am interested in acquiring multiples, rather than single images. I do not look at individual pictures; I always look at bodies of work. I am very much driven by series, tableaux, typologies, and taxonomies. When I support artists through acquisitions, I like to maintain the possibility to collaborate with them in the future, on dedicated projects with the Collection – publications, exhibitions, commissions or events.

Would you grant us a sneak peek into your “hot list”? Whose work has recently caught your eye? How long does it usually take until you decide to acquire an image? Are you more of a spontaneous collector who acquires art while browsing at a fair like Paris Photo, or are you more cautious, basing your decisions on in-depth research of artists’ market value and then working out a strategy to invest in their works?

AW: The Foundation’s approach to photography is educational: to assemble, to research, to publish, and to exhibit photography as a crucial record of social change. A key aspect since opening the museum campus in Neu-Ulm in 2010 has been to present the works of artists from Africa and Asia in dialogue with Western artists. In this regard, the Collection has published several visual studies on recent photography from Asia, as well as numerous books on historical and contemporary African photography. Another goal of the Collection in recent years has been to expand the visibility of vernacular photography in order to recast existing histories of photography, and to insert into those narratives objects and questions that have often been ignored or erased. In doing so, we aim to explore what the history of photography might look like with everyday images inserted, but also to consider what these ‘ordinary’ photographs might tell us about social patterns and human behavior? To collect global vernacular photography was a logical progression from our investment in African, Asian, and Western photography and an area we are still keen to expand further.

Hence my collecting strategies are always deeply linked to the conceptualization of forthcoming exhibitions and publications in development, with the view to expanding and deepening a thematic exploration, and also in relation to existing works in the Collection. In most instances artists’ work is researched rigorously prior to acquiring, yet occasionally auctions or art fairs offer works that reflect the Collection’s focus and fit perfectly – for example, I bought Yinka Shonibare’s first performative photographic self-portraiture works from 1996/7 at auction in 2017. These will be on public display at a major museum exhibition for the first-time next year. We are currently in the process of reviewing gaps in the Collection and are actively researching important additions to further develop the representation of contemporary artists from Africa and its diaspora.

One of the current shows on display is a huge retrospective by the African artist Samuel Fosso. When did you start collecting his work, and what about his work makes it so special to you?

AW: Over the years I have often returned to the rich catalogue that accompanied the Guggenheim’s In/sight exhibition, and have long been captivated by Fosso’s work. I was first introduced to Okwui [Enwezor] in 2003, who by then had organized both the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale as well as Documenta 11 in Kassel, and as mentioned earlier his guidance and advice had a lasting influence on my collecting: he not only encouraged my interest in African photography, but also informed my thinking about non-European approaches to the medium. He was also instrumental in my decision to build a museum campus in Neu-Ulm, Germany – in the street where I grew up. By the time I formally established The Walther Collection in 2010, Fosso’s photographs were already represented with several bodies of work—often at Okwui’s suggestion—beginning with his early 1970s-era black and white studio self-portraits and his performative color series “Tati,”. I later added “African Spirits” and selections from other key projects made between the early 2000s and the present. Fosso was a central figure in the Collection’s first exhibition Events of the Self: Portraiture and Social Identity curated by Okwui in 2010. His works were positioned in dialogue with other celebrated West African studio portrait photographers such as Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, as well as contemporary artists considering performance, representation and identity, including Oladélé Ajiboyé Bamgboyé, Candice Breitz, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Zanele Muholi, Grace Ndiritu, and Nontsikelelo “Lolo” Veleko, to name but a few.

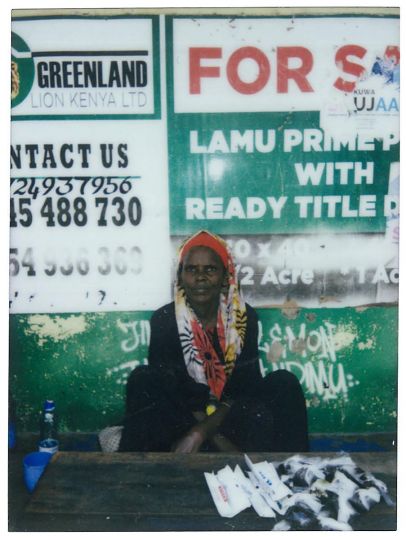

We recently published – in partnership with Steidl – two major monographs dedicated to the work of Samuel Fosso: Autoportrait, the first comprehensive survey of his self-portraits; and SIXSIXSIX, a series of 666 large-scale Polaroids made in his Paris studio between October and November 2015. These days we often work in collaboration with other institutions – the exhibition Samuel Fosso: The Man with a Thousand Faces, currently on view at our museum campus in Neu-Ulm until November 20, 2022, is a collaborative touring exhibition organized by the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, The Walther Collection, and Huis Marseille, with the support of Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne.

How do you juggle planning exhibitions, traveling the world, and finding new works for your collection? Do you have a particular schedule that you follow?

AW: Throughout the past decade we have invested considerable efforts to balance an ambitious, rotating schedule of exhibitions presented in our own exhibition spaces, while also organizing travelling shows that display the Collection in other spaces internationally. For eleven years, we have curated three exhibitions a year at our former Project Space in New York – now permanently closed – and one large-scale annual exhibition at our museum campus in Neu-Ulm. The Collection’s team is small and currently based between Neu-Ulm, New York and London and together with guest curators we continue to actively develop our exhibition programs in Europe and America, as well other places globally. At times, these programs are challenging – for example, in 2018 we concluded three exhibitions in New York; one in Neu Ulm; and six traveling exhibitions in Mexico, the Netherlands, Spain, and Mali. The schedule for each year is often influenced by art fairs and festivals such as Paris Photo, Photo London, Art Basel, and AIPAD in New York, as well as Rencontres d’Arles, the Venice Biennale or Documenta. And as mentioned earlier, new acquisitions for the Collection are always driven by the planning of future exhibitions. There has been extensive traveling over the years, visiting artists in their studios and learning about their practice, which is one of the greatest pleasures of my work as a collector. The concentration on Asian and African has unique challenges for traveling exhibitions, but throughout the years it has created a certain rhythm and unique focus which we are keen to develop further.

What’s next for you and your collection?

AW: We will continue to expand our traveling exhibition program globally in order to bring the works of significant artists that may be unfamiliar in some cultural contexts to a wider audience, alongside developing our publishing platforms. We currently have more than 500 photographic works from Africa, its diaspora, and Europe on view in the exhibition Shifting Dialogues: Photography from The Walther Collection at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf, Germany. The exhibition, curated entirely from the Collection’s holdings, traces the development of photography as a history of transnational parallels, from the beginnings of nineteenth-century ethnographic imagery to studio photography from the 1940s onwards to contemporary visual activism, portraiture and documentary practice. 2023 is an exciting year for us – a prestigious institution in Germany will present a major exhibition which for the first time will draw on all aspects of the Collection in what will be our most ambitious public presentation thus far.

What’s your advice for the new generation of photography collectors?

AW: Follow your intuition: collect artworks that attract you, that speak to you, inspire you, make you think and reflect deeply, and make you laugh or find pleasure. Reflect carefully on what you wish to acquire, and try to analyze, conceptualize and articulate why it attracts you, and only then pursue it. It is as general and as specific as that. Try to look at images wherever you can, in galleries, museums, studios, and read about the artists’ practice in publications. For me, it is all about looking: by looking at images and books, which I believe is still the best medium to research, one trains and sharpens one’s eye, developing a feeling for one’s individual points of interest and inquiry.

_____

For more information, please visit: www.walthercollection.com and check out its IG account @walthercollect

The exhibitions:

“Shifting Dialogues: Photography from The Walther Collection / Dialoge im Wandel. Fotografien aus The Walther Collection” is on view through 25 September 2022 at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen

“Samuel Fosso: The Man with a Thousand Faces / Samuel Fosso: Der Mann mit tausend Gesichtern” is on view through 20 November 2022 at the Museum Campus of The Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm.