Art is not a thing, it is not a subject, it is not something that you can grab or understand. Art is a vehicle, a filter; you have to pass life through it in order for it to work.

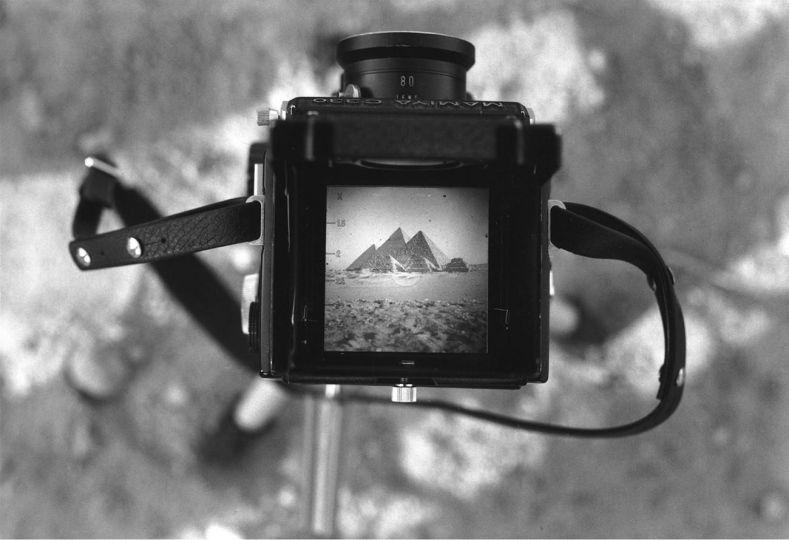

Muniz sees himself precisely as Cézanne or Matisse; easel painters, people who took their canvases to the landscape and painted what they were looking at. Muniz is doing the same thing, but his landscape is different. His landscape is the result of a cross referential maze of loaded images of every preconceived image full of what has come before it. Every image has attached to it the memory of that image and the memory of making that image. We see too many images and the images are very complicated. If we are going to reproduce the world as artists, that has to come with the same complexity as the world, but, in order to do that you have to start from the very beginning.

Art is all about realizing and updating rituals in which mankind deals with their environment, the duty of the artist is to help realize but also to update the idea of realism itself. Children can rotate objects within a special field, when we grow old we lose this ability. When we are older we conceive objects from a specific vantage point, when we are dealing with an object we put the object on a pedestal and we rotate it until we find a match that we can view from the same vantage point that we had in our minds. The history of representation is the history of technology – from cave paintings to photography.

All of the above is paraphrased from a lecture Muniz gave on contemporary perspectives; it is as close to a distillation on Muniz’s visual theory as there is. Not only a visual artist, Muniz is a prolific writer, lecturer and teacher. All his images can be tied together through his investigation of what the difference is between what an image looks like and what it is.

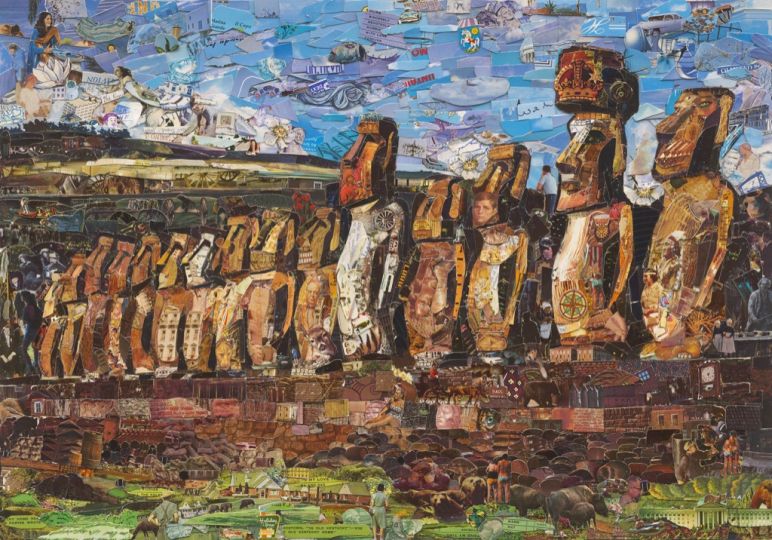

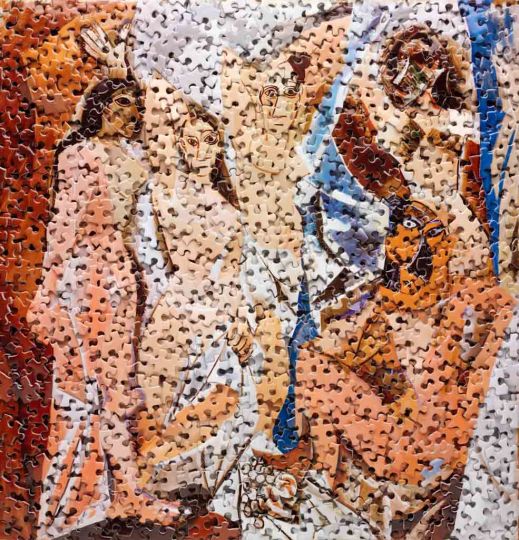

To examine the area between image and representation, or image and memory, Muniz employs the kind of instantly recognizable poster store iconography that make up his most popular work. A pile of junk in the shape of a Titian, a plate of caviar creating an image of Karl Marx. His choice of materials, for the most part, make a statement about the image he is creating. In Muniz’s early work with string, he found that the topography of the string on the paper made landscapes, influenced by their own topography, a natural process. In other works, he creates a soldier from toy soldiers and turns Warhol’s (not DaVinci’s) Mona Lisa into PB&J. This can be interpreted easily and heavy handedly as soldiers used as toys or the Mona Lisa as the most recognizable image from the most recognizable food of the world’s premier consumer culture. Muniz is humble and unpretentious, he is asking questions about image representation mostly for himself, for the audience he is making a picture of spaghetti sauce that look like an image they have seen before. We are all, from a child who has never been in a museum before, to a debt-ridden MFA student, in on the joke and that’s the fun part.

His most entertaining works are predictably his most popular, things like Sigmund Freud in chocolate. Muniz likes to playfully remind us that chocolate is tied to romance and sex, but also it looks like poop, and the first person to be able to explain this relationship would be Freud. That work is a perfect microcosm of Muniz’s work – a low barrier to entry that we can all enjoy (read: poop is funny), to a more nuanced examination of the subject (read: Freud actually did have a lot to say about feces and sexuality).

This place of low floors and high ceilings is where Muniz likes to play. Muniz works encourage the viewer to see them from many different perspectives, the first is a quick glance and a reading of the image as something we know, the second is to get up close and see what the image is actually made of. In the Pictures of Junk series this is a Caravaggio made out of trash. Muniz found that people like to know what is what in a picture and would get close to his images and say out loud to no one in particular what was in the picture: “Oh, that’s a tire! Wow Diamonds”. Muniz also notes that people, particularly people on dates, like to remark out loud when they recognize an art work; “Ah that’s a Klein, you can tell by the blue.” It is a good time at the museum.

Form follows function, but you can use an Etruscan bronze to hammer in a nail.

Trash pickers in Brazil are depicted from recyclable materials in his “Pictures of Garbage” series. A series documented in the film “Waste Land”. In one image, styled on the death of Marat, the leader of the garbage pickers union Tião plays the part of Marat. A modern-day union activist playing a dead human rights activist, all in garbage. This work was later sold at auction and the entire sum given to the workers’ union. In a nice bookend, near the end of Wasteland we see Muniz showing Tião Gavin Turk’s Trash.

Later series become even more self referential, a rough drawing of a cloud drawn in the sky by a plane – a cloud that is a picture of a cloud drawn using clouds. Something Muniz has been interested in since his early work with cotton cloud creations. People can see anything in clouds, but they can only see one thing at a time.

In another series that focuses on reproductions of minimalist sculpture in the Whitney, Muniz collected dust from the museum to recreate the image of a Judd or a Serra, creating a dichotomy between the permanence and strength of the sculpture and the fragility of the medium; it is also very small when those sculptures are normally very big. This kind of playfulness with scale and expectations comes when Muniz recreates land art like Spiral Jetty in his studio using some dirt. This kind of fascination with size has informed his most recent works. Muniz will draw huge line drawings in the desert using bulldozers and photograph them from the air, but he will then display them next to line drawings in dirt photographed from a few feet away, as ever Muniz is forcing the viewer to look closer. In the world of Muniz ”forcing the viewer to look closer” could be written as messes with the viewer, teases the viewer, tweaks our nose and laughs.

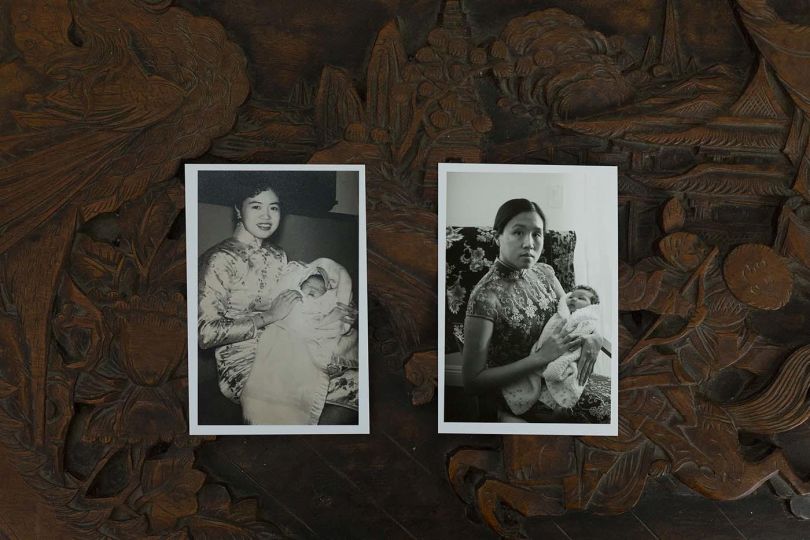

Some of his other work; the Postcards from Nowhere use postcards to create what are essentially stock images of well known places. His skill with collage is visible within Postcards from Nowhere as he uses it once more in his Family Portraits series where Muniz uses found family portraits to create idealized versions of family portraits. Each one has almost infinite depth and scope, visual jokes and clever placement of the found pictures. One piece in particular from Family Portraits stands out. Amidst the pictures of children learning to ride bikes, families blowing out candles on cakes and Dad cleaning the car is the mug shot of a 14-year-old boy. The youngest person ever given the death sentence in the United States; he is the only black face in the entire series.

Muniz, a brilliant curator as well as his other talents, recounts a story where he was approached by MOMA to curate a show; “My retrospective!” he asks excitedly. It was not to be until this year however, MOMA giving the excuse that Muniz was so prolific the museum could not fit enough of his work to do it justice.

Vik Muniz’ new series, entitled Epistemes and currently on view at Sikkema Jenkins & CO in New York, combine the material object and photographic trompe l’oeil into a unified abstract composition. Commenting on the confounding image-object relationship probed within these works, Muniz observes, “It always goes both ways. What you expect to be a photo isn’t, and what you expect to be an object is a photographic image.” Extending this idea more broadly, Muniz adds, “In a time when everything’s reproducible, the difference between the artwork and its image is all but nonexistent.”

While not referencing specific artistic antecedents in Handmade, Muniz’s vocabulary draws connections to abstract art movements including concrete art, constructivism, and op art. The exhibition’s title is taken from the philosophical term “épistème”, which theorist Michel Foucault introduced in his book The Order of Things and refers to the implicit structures that set the conditions for the production of scientific knowledge in a given time and place.

John Hutt

John Hutt is a writer specialized in arts based in New York, USA.

Vik Muniz, Epistemes

February 23 – April 1, 2017

Sikkema Jenkins & CO

530 W 22nd St

New York, NY 10011

USA