She would sometimes say that she had three vocations in life. The priority she gave to them changed with time, but their content and her love for them always remained the same.

— Preserve the memory of her parents, Russian Avant-Garde artists Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova.

— Treasure her family and Home. First her husband, the book artist and photographer Nikolay Lavrentyev, and her son; then her son and his wife Ira; then her granddaughter Katya; then her husband, Alexei, and her great-grandsons Alexander and Nikolay…

— To create, make art, paint, take photographs, and design books.

She always took a creative approach to all of her responsibilities.

She begin her work as a book artist after graduating from the Polygraphic Institute in 1947, at that time still working alongside her parents. Several publications in the early 1950s were prepared jointly by the ‘Rodchenko-Stepanova-Lavrentyev brigade’. Later, after her parents passed away and she had only recently turned 30, she went to the artists and writers who had known her parents — Ilya Erenburg, Lev Kassil, and the Kukryniksy — with a request that they write something in their memory and support the idea of publishing books or organising exhibits. She restored the posters, advertisements, and exhibit notices that had been lost by publishing houses in the 1920s. She framed and hung their works, selected illustrations for books, and made layouts for albums as a print artist. She explained the meaning behind the works of Rodchenko and Stepanova to art scholars from various countries. At the authors’ first request, she selected and prepared materials for books about Mayakovsky, Soviet photography, Avant-Garde architecture and design, theatre and film, literary history, and music. It turned out that her parents were quite familiar with these fields and were counted as ‘one of their own’ — all thanks to this quiet, meticulous, and unnoticed work. ‘I work backstage’, she would say whenever she was invited to speak or appear on television or in newsreels. She was very glad that she could participate, helping create the first exhibits at the Moscow House of Photography and later at the Rodchenko School.

For her, the notion of ‘Home’ was always multifaceted. Of course, it was a space for family, household cases and wellbeing, even in those years when she earned very little. She always worked on contract, as she believed that she should always be present at home: ensuring that everything her husband needed was in its place and that everyone was well-fed; so that work and study went smoothly; so that the results of the work were worthy of her Home. Therefore, she might gently convince people to re-do what seemed to be an already completed object. She believed that the family should always stay together, and that everyone should preserve and protect the things that depend on them. That’s why everyone in the family wrote each other New Year’s wishes. For anyone who came to visit her, from postmen, couriers, and building superintendents to an editor from a publishing house, magazine employees, or fellow artists, she always tried to sit them down for tea and treat them like members of her own family. Her home served as a location for the widest variety of meetings. Sometimes, after she met new people, she would invite everyone to visit. Her ‘family’ included acquaintances and colleagues; she knew how to find everyone a task of some sort that would tie them to her, and that person would always be happy to become a part of history. She would proudly tell each of her guests, ‘Mayakovsky sat on this chair’.

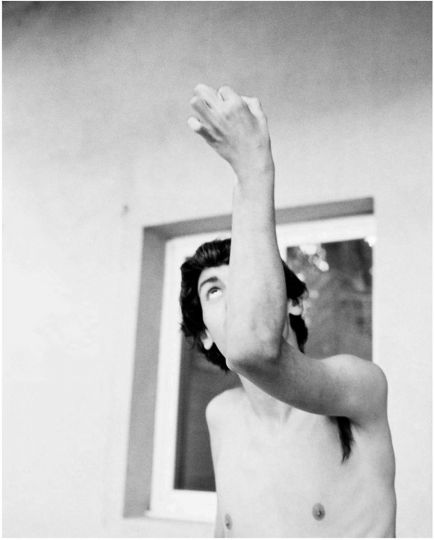

But every artist has their personal life. For her, this life began with her first still life, which her father set out in 1943 upon her arrival in Moscow after their evacuation to Molotov (now Perm). Upon seeing the result, he said, ‘Now you always have to paint’. She kept her word. She tried to make every summer a time of relative peace and quiet at work, to take the whole family to the dacha, feel free from her cards, and just paint landscapes and flowers. She started with oils, like her father taught her. This cycle during the summer at Abramtsevo was captured by Nikolay Lavrentyev, who later made her an entire photo album that told the story of how a landscape came to be — from primed cardboard to a finished étude. Next to them, he placed the artist herself and a photo of the landscape she was painting. But painting with oils takes time and concentration, so later on, she preferred doing watercolours on unprimed paper. She was especially talented at painting clouds. With one brush stroke on fresh paper, she would conjure stormfronts or melancholic, heavy rain clouds, conveying the contemplative feeling of a sunset sky or a windy afternoon. Water and watercolours created the landscapes practically by themselves. By the 1980s, after getting settled on her garden plot where her granddaughter would continue to grow and later join the neighbour girl in painting still lifes, she asked to have a photo lab built in a tiny empty hut. Here in the Moscow region, near the Zagornovo station, yet another series came to be: her photogram portraits. From wildflowers, herbs growing in flower beds, branches and leaves, she put together portraits of her friends and acquaintances. She liked experimenting, and she tried to transfer the principle of photograms (essentially, silhouettes of objects serving as stencils of a sort) to watercolour painting. Her bright, decorative panels of flowers and leaves were made this exact way: by placing a real flower or fern leaf on paper, she painted them various colours using a brush. Regardless of the seeming simplicity of the approach, the sense of flowering meadow nevertheless came through.

Creativity exists wherever there is a chance to show oneself. Yes, she was a professional at creating photo collages, covers, political posters, and magazine spreads. These were commissioned works. But in order to remain herself, you have to do something ‘for yourself’ as well, as she would say. This freedom and need for creativity was taught to her by her father, Alexander Rodchenko, and her mother, Varvara Stepanova, who also loved to paint sketches in the summers.

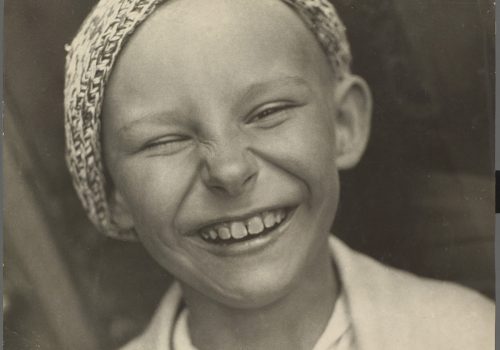

The story of her life, appearance on earth, growth, and old age were all preserved in photographs. On the outside, people change, of course. But on the inside, for him or herself, they stay the same as in childhood. The clever look on one-year-old ‘Mulka’s’ face, as her father would call her; the wild laughter of the little girl with a hat on her shaved head (at the time, it was believed that children should sometimes be shaved clean); and the patient smile of ‘great-grandmother’, in the striped skirt that little Kolya would cling to — this was all one person. She forever stayed the same little girl to whom Vladimir Mayakovsky once dedicated his children’s book: ‘To Mulya Rodchenko, from Uncle LEF’.

Alexander Lavrentyev

Varvara Rodchenko : Elapsed time

Until December 8, 2019

Multimedia Art Museum

Moscow, Ostozhenka str., 16