Technology, talent, and tolerance. The T3 Tokyo Photo Festival gathers around these three words starting with the letter T, echoing Richard Florida’s theory, The Rise of the Creative Class (2002). As one strolls among the exhibitions in the official program as well as its satellite program, a fourth word should be added: tribulation.

While the festival and its fair primarily gather in the Midtown Yaesu building, the festival expands into the streets of the Kyobashi business district. However, to describe Kyobashi with this ordered word does not do justice to the entanglement of anonymous buildings stacked on top of one another, overshadowed by gigantic skyscrapers, scarred by construction, and tickled by small, smoky eateries or idle spots.

Kyobashi reflects Tokyo in its most contemporary and perhaps most bustling component, crisscrossed by wide American-style boulevards and lined with tiny alleys where offices for stamps and noodle vending machines lie dormant. The area resonates with construction, sometimes punctured in its vertical horizon by a gigantic construction site, a vacant lot promised to grandeur, which in the meantime is methodically excavated by enormous cranes.

Discreetly, and herein lies the pleasure of rummaging, the satellite programming unfolds all around the central station and the main venue of the festival. There are portraits by Yuta Fuchikami in the staircase leading to the restrooms of the Nihonbashi Philly pub; the portrait of the pastry chef who runs the Momoroku café, taken by Fuchikami at her home; or, guess what, ethereal morning scenes by this mischievous Fuchikami on the walls of the Kimura restaurant.

The festival demands special attention. It reflects Tokyo for those unfamiliar with the city; an invitation to notice the details, to force its nature, to push the door open, and enter the alleys. It aims to be unexpected in these places, in a city where what is façade is not necessarily reality, or where reality hides behind the first view, behind the façade.

It requires attention, a slowing down, a demand for focus. Thus, the very beautiful series by Ayaka Endo, Luminescence Land, discreetly settles on the numerous barricades surrounding, or inversely, a construction site for the Yaesu Nakadori tower. A gigantic construction site, an enormous fence, the mystery of what is being built clashes with the subtlety of the photographs running along the iron sheet. The fence, a place of the temporary, often ignored, flips its own function by welcoming Nakadori’s call to nature. One can see the wild horses of Tono plains in northern Japan, and the series strongly contrasts with the ballet of workers along the boulevard throughout the day. A great softness emanates from it, tapping into the eternal appeal of freedom, the wild, the mythological.

Another construction site, another fence, another exhibition at the corner of the next street. Hiroyuki Takenouchi urges the viewer to question space and time. His series Warp and Woof places his subjects (portraits, landscapes, and details) on the same plane to emphasize the importance of vision in how we comprehend the image — the shift of an angle or point of view invites us to constantly reconsider an image and, thus, our understanding of it. Nevertheless, his somewhat conceptual work struggles to withstand the direct confrontation of the street, with its anonymity and relative indifference.

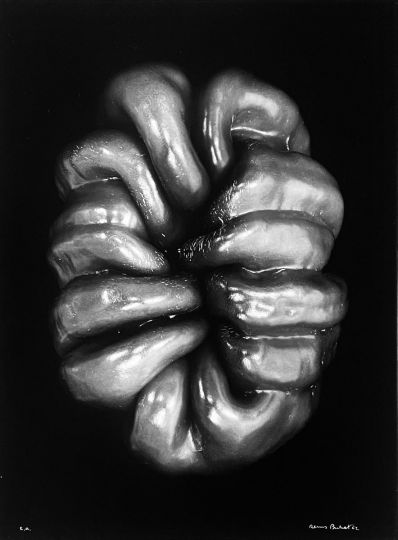

Finally, the festival also bounces from entrance hall to vestibule. This is the case for the exhibition New Japanese Photography In New Light, which is presented both on wooden panels and with monumental prints. Curated by the honorary curator of SFMOMA, Sandra S. Phillips, the exhibition occupies five different locations and counters the historical exhibition at MoMA titled New Japanese Photography. The latter showcased fifteen artists (all male) and was retrospectively considered a revelation of the Japanese photographic scene. By revisiting these same figures, some of whom have become iconic in Japanese photographic art (Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Shomei Tomatsu, Daido Moriyama, Eikoh Hosoe), but presenting them across different venues, the curator also allows for a break from an encompassing narrative that aims to group them in a single movement, in a single generation, and invites everyone to reflect again on the most fundamental aspect: from image to work.

More information