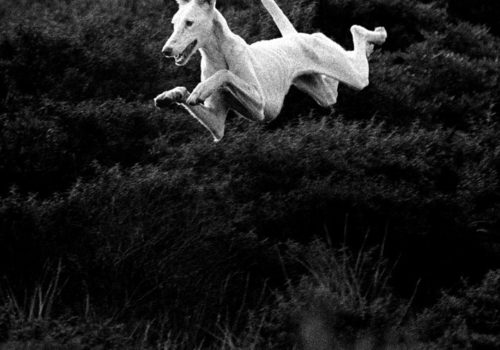

My father Sam Haskins, in the last years of his life, maintained a regular correspondence with only one photographer, Charles Camberoque. They affectionately referred to each other as ‘Uncle’. In our home, Mr Camberoque was famous mainly for being Charles, for the man, for his intelligence, warmth, generosity and a wide ranging articulate understanding of photography. Sam also made sure that everyone got to see Charles’ famous hunting dog pictures – the balletic Ibizan hounds hunting rabbits in the hills of Majorca.

In the course of researching Camberoque’s career output to write this article, I was able to put the hunting dog pictures into a far more nuanced understanding of this wonderful photographer’s career. There is a celebratory, romantic, idealistic streak in Camberoque’s photography which finds expression in early off-road motorcycle racing and the fast Roman based Tambourine Ball Games of the Herault region in the South of France and most iconically in the Marjorca hunting dog photographs. Here is life, athleticism, incredible agility, tradition and beauty but here too is death, these dogs kill for their far less agile, heavy set owners. Yet there is harmony too, this is a legitimate sustainable harvest from the land and both dogs and owners are eager to enjoy the freshly killed flesh. As such the hunting dog images are the cross over from the idealistic romanticism of much French photography into a much deeper poetic place frequently filled with melancholic beauty, which characterise the real quiet power of Camberoque’s themes and images. Like any great photographer you feel you know Charles the man through his images, the sadness and the beauty, the intense empathic sensitivity to life are all finely carved and perform a very precise dance within his camera. The one constant whole hearted celebration in Camberoque’s work, is photography itself. His knowledge of photography is both scholarly and visceral, he has internalised the lessons of past masters and the understanding rests with a gentle certainty in his images.

Another characteristic of Camberoque’s artistic ‘signature’ is a complete lack of pretentiousness. This is an intelligent man, drawn to examining the passage of time, empathising profoundly with rural people and their relationship with their surroundings, employing a combination of awe and a poignant longing in his photography. Many of the images are devoid of people and yet the lives that once lived in those spaces or who do live there now are experienced through the trace of their actions with Camberoque’s sensitive enigmatic eye. Even his most minimal images invite repeated viewing and constantly reveal new layers of understanding.

One image contains, with utter simplicity, two white kitchen tea towels hanging on a wall, but they are not in the least banal. One quickly tunes in to Camberoque’s passions, he is always on the lookout for the visual passage of time, for the trace of lives, for the narrative of man’s relationship to the land and the way that containment and identity grows out of the simple business of living. In a very fine and respectful way he is constantly aware of death, or more precisely, of the process and passing of life. The two tea towels evoke this experience in the viewer, almost magically one feels all the meals that were eaten, the harvest of the land consumed, the human process shared, the washing up, the countless times that these towels have dried dishes, ready for the next meal and then the towels themselves were washed and ironed and hung back on the wall, constant cycles of life, nourishment, voices, growing, learning, containing, maintaining traditions and then – the passing of the physical, the fine but insistent awareness of death. Camberoque is drawn to these ‘trace markers’ like a magnet, repeatedly describing life with the physical marks left on the land, house foundations, railroads, roads and inside homes, light spilling through windows onto vacant desks, ceramic containers, maps, dead flowers in vases. You feel the people intensely – even though they are absent.

To the extent that Mr Camberoque does photograph the people of the Mediterranean he is fascinated by ritual and rites – carnivals, weddings, bull fights. His camera searches out dark corners of the human psyche and reveals and distils a great deal while doing so with a light touch. We live in an age where a generation of young photographers are queueing up to go to war. Camberoque’s works serves to remind them and us that the photographs of life and death that exist right under our noses are equally resonant and perhaps longer lasting.

Ironically, given the nuanced beauty of his photography and the universal nature of his passions, Camberoque seems better known in China than in France! China, a country he first visited in 1981, has had a very engaging influence on his work. Far from his beloved Mediterranean and its islands, he has put his arms around the Chinese people by pointing his camera straight at them. In a far away land, his need for poetic adjacency seems supplanted with a more direct body of human imagery. Here you see puppet masters taking on the appearance of their puppets. Chicken farmers parody the great Mao’s heroic pose. The extreme poverty of the Chinese interior is contrasted with sexy self expression in the coastal regions of a 1993 China racing out of economic conformity and isolation. There is a direct tenderness in these images, an empathy and love for the people which is all the more profound for its quiet respect of the lives in front of his camera.

Charles Camberoque is a hidden gem in the history of French photography. It would please Sam enormously to know that Uncle Charles’ work is being championed by the editors at La Lettre. Something which has become evident to me through my father’s death – the dead don’t disappear, they live on in a multitude of ways that link the living to the ancestry of their families and communities. Charles Camberoque is a master of that understanding.

Ludwig Haskins

Charles Camberoque is a French photographer and teacher of photography, in the early part of his career he taught in Paris and since 1982 has been on the faculty at Ecole des Beaux Arts in Montpellier.