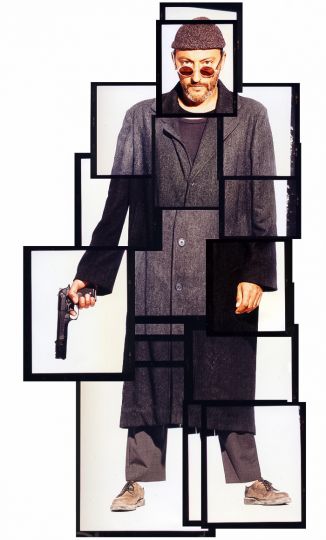

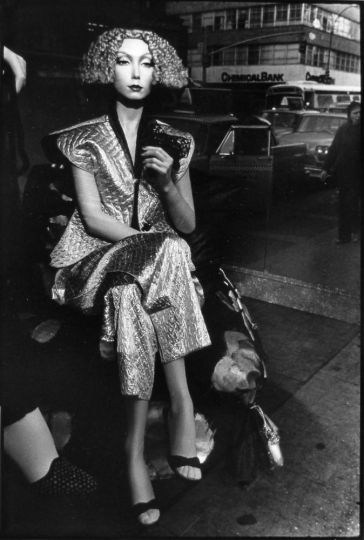

What drives photographers to risk their lives reporting on violence on the other side of the world? Their reasons are often complex, a combination of personal and political conviction, a desire to go beyond impersonal abstraction: “War, Battle, Death.”

They all agree to report on what makes each conflict specific. Fabio Bucciarelli, who just received the World Press Photo award for his reporting in Syria, explains: “The main reasons why photographers go in the field to cover the war to document what is really happening in a country where thousands of people suffer from the cruelty of war. Without photographers or video makers, “our world” would not know exactly what is happening in the other side of the world. Their presence is essential to the information.” Without claiming they affect the situation’s outcome, they want at least to document it, to spread awareness, to engage people in an intimate knowledge of the world they share.

This mission, where censorship is never justified, is also described by Alan Chin,: “I think anything we can see should be seen. We are supposed to be the eyes and ears of the people, the fourth estate, right? Why else are we there? The reason is that we are the eyes of the historical record, and that historical record should be as complete as possible.”

The conviction of the absolute necessity of informing, the desire for completeness and universality, lead them to accept the risk. Jake Price has worked on Japan since the March 2011 earthquake, knowingly exposing himself to radiation: “I have a strong attachment to Japan and I wanted to tell the story of its people as comprehensively as possible, in all its complexity. I believe that society should be informed. Photography is real work. Photography has an aim, but it isn’t self-sufficient. Risk is part of the job, and you have to accept it.”

To accept but not to ignore it, as Pete Muller emphasizes: “It’s interesting how we become such refined judges of danger. 90 percent of our work occurs in places where the average person would never go. Amongst ourselves, we end up talking about the risks in such precise terms. Certain roads are ok. Others not. We consider the risk of kidnapping almost in terms of percentage. From an outsiders vantage point it all must seem insane.”

None of these photographers harbors a fascination for danger or having their names in the papers. What they have in common is, as Jehad Nga describes, an ability to engage in favor of the collective, they insurance that they have a role to play in the theater of the world: “Occasionally there tends to be what feels to be an uncontrollable urge to go somewhere, but out of a certain loyalty to my own set principles I force myself to suppress it. It is crucial to remain honest and true towards your role and to ask yourself how that role will fit with a story. We are out own judge and jury in these cases. I refuse to take a single step forward before I am able to figure out my part in the bigger picture of a place or hyper point of an event. This rule is the holy trinity for me and history our highest law. For every place I might go there could be 10 places I failed to clarify my place with and therefore I don’t go. I don’t go because I am not convinced that I would have any part in elevating that story with my ideas nor believe that any more eyes will turn in its direction because of my contribution.”

The myth is over: the images do not change, or very rarely, the course of events. What they change is the way we look at the chaos, forcing us to define our role within it.

Laurence Cornet