Evidence and analysis are at the heart of the historical and journalistic endeavour. To discover what was done in photography, who did it, when, and how it fits into the big picture takes time. With trillions of images being made every year in this digital 21st Century, the task of locating, preserving and documenting photographs of significance for the edification of present and future generations is never ending. The backlog, especially of analogue images is huge and there is a serious danger of major collections being destroyed because they need more physical storage space than digital. There is now a greater need for picture librarians, curators, writers, editors, and historians of photography to examine the work of dead practitioners and elderly living practitioners to gauge the significance and use value of often large and unique bodies of work. Especially those quietly revealing significant aspects of their life and times behind the scenes, as it were, without any ambition for fame and fortune.

This, of course, is what the editors of L’Oeil de la Photographie (The Eye of Photography) work to do for an international audience. Photography plays a huge role in nation building, in both the public and private spheres. Our knowledge of different people around the world may be slight if we have not travelled widely, but we can nevertheless build up our own understanding of similarities and differences from the pictures we see. Historical photographs take us back in time to better understand our histories and cultures and we are becoming better able to see the difference between honest documentation and propaganda – to detect patterns of intention and results from afar.

Specialist teachers and are also needed to help the population better understand the paradoxical nature of the medium as a means of communication and expression which, confusingly, can be one and the same: a convincing optical record of its subject and a personal statement (artistic expression). Studying historical photography is fertile ground for anybody inclined to enjoy the challenge of detective work with its numerous frustrations and the joys of discovery. One thing always leads to another and there are always new questions waiting to be answered.

Why some photographs stand out more than others leads to wanting to know more about the subject matter and the maker. Did the person who created a certain picture which stuck in our memory make other memorable images that intrigue us with their content and form? What is it that adds up to a distinctive signature that sets itself apart from the work of others and confirms authorship?

These thoughts are brought to mind by my first look at the recent publication of Through Shaded Glass: Women and photography in Aotearoa New Zealand 1860-1960 by Lissa Mitchell, the Curator of Historical Photographs at The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington. Coming from a background in experimental filmmaking and art history she was well aware that less had been written about female photographers than males during the first hundred years of photography – worldwide – and determined to find out who and how many female practitioners had been overlooked compared to their male counterparts?

New Zealand’s population has never been high by world standards. It was around a third of a million in 1860 and only two and a half million by 1960 the cut off point for Mitchell’s book. The country has since doubled its population which is considerably smaller than many cities around the world. This book reveals that she managed to 190 female photographers and assistants engaged in some form of photographic activity, including a handful of Maori practitioners about whom little was known, and flesh out something of their stories to bring to their experiences and work to life.

Lissa Mitchell does not hide her feminist bias, so there is no comparison of how many men worked in the industry or as serious amateurs, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it was no more than perhaps twice that number. As one who has sought a balanced view of the histories of photography in my native country and elsewhere, I am very much aware of how little is still known about the work and lives of some of the most significant local pioneers who happen to be men. People like David Monro, a keen amateur from the 1860s who was knighted for his work as Speaker of the House of Representatives; Edward Payton, the founding director of what became Auckland University’s Elam School of Fine Arts who ran photography classes on the cusp of the 20th Century; and Clifton Firth who was a rarity as a photographer of celebrities, fashion trends and glamourous nudes in the 1940s 1950s. The list goes on, but we should not expect a similar investigation into pioneering male practitioners, some of whom are mentioned in passing as spouses, either as the wayward or more reliable kind, with little room for telling their stories.

Mitchell’s thorough investigation confirms the value of primary research into the lives of many barely known of or simply overlooked to date. Consequently, it is a major contribution to what is known about the nature and use of photography in New Zealand, which is a small South Pacific country whose indigenous Māori people were colonised by the British empire at the very time the invention of the daguerreotype was announced in Paris in 1839 and forced other inventors to present their claims to fame.

It took another 130 years before Hardwicke Knight’s pioneering survey Photography in New Zealand: a social and technical history was published in 1971 and helped to spark more interest in this subject, as did my touring exhibition ‘Nineteenth Century New Zealand Photographs’ of 1970 which found an interested audience.

Mitchell is an astute editor of images and narrative, with the written records and visual evidence telling their own but related stories because part of the mix is still missing. Often, where a name is fleshed out from news items or whatever, authenticated images appear not to have been located, or vice versa when a portrait of the photographer is featured but none of her own works are presented, as is the situation for over two dozen cases, so the quality of their work cannot be gauged. Through Shaded Glass… is obviously an open-ended work in progress aimed to ‘recover the identities and stories of women who have been hidden from history. Its deliberate focus is on individuals, not to argue for them as exceptional but rather to combat anonymity and generalisations, particularly in the case of working-class women.’

Care has been taken to make Through Shaded Glass…. A handsome, well designed and well printed book appealing to a broad audience, with more than 360 pages and over 240 illustrations. All of the 190 women she registers were known to have been active in some aspect of photography between 1860 and 1960 either as amateur enthusiasts or active commercial photographers, or as studio or field assistants added to fill the ranks. As such it is a valuable addition to David Eggleton’s Into the Light: a history of New Zealand photography (2006), and earlier publications by the late Wiliam Main from the 1970s, with whom I co-authored the Photoforum anthology of 80 photographers: New Zealand Photography from the 1840s to the present (1993). Main had compiled a history but failed to get it published and was always on the lookout for women photographers to add to his books such as Wellington Through a Victorian Lens (1972) and Maori in Focus (1976) among the earliest. Surprisingly there is no mention of Joan Woodward’s A Canterbury Album (1987) in Mitchell’s bibliography.

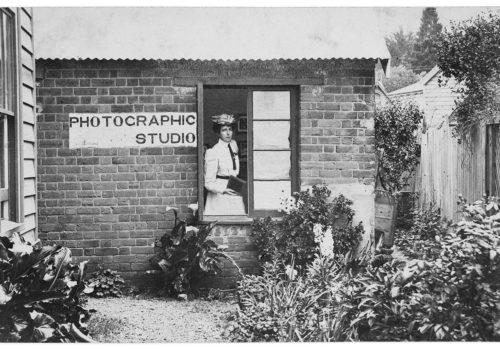

The chapters in Through Shaded Glass…. are organised in the sequence of The Photographic Studio; In Business; The Art of Studio Photography; Being Modern; Homemade; and On the Move. The move, as is the convention, follows fashions toward modernity and public recognition in the art world as it wakes up to the power of photography as a means of communication and expression. Then there is the Epilogue; Women Photographers and Makers, listed according to when individuals are mentioned in the book and including the period worked if birth and death dates are not known. There follows a Glossary of Photographic Terms, a brief note About the Author; a rather slim Bibliography; extensive Acknowledgments and a valuable Index. Her meticulous endnotes throughout the volume, however, partly make up for the less useful bibliography.

Among the niggle’s I have is her fanciful ahistorical use the prefix Aotearoa added to New Zealand in the subtitle and throughout the text because the now popular “Aotearoa New Zealand” was rarely if ever used during the century covered. I also find fault with the attempt to create a category of “makers” as a ploy to argue that hand colourists (predominantly women) and other studio assistants should be treated as co-authors of images by the actual photographers. The concept quickly runs out of examples but if taken to its logical conclusion would have every handmade photograph credited like a movie with acknowledgements to everybody and their dog who had contributed to the final product.

Rather, I argue that hand coloured prints of the period altered but did not change the original content of an image. Hand colouring was carried out mainly for commercial purposes through a painterly “artistic” veneer for an audience blind to the nuanced colours of so-called “black and white photographs” where tone, texture, scale and so on expressed emotional as well as optical renditions of subject matter. Learning to deduce a photographer’s intention required more attentve scrutiny. Nevertheless, as Mitchell shows from her choices that some early hand coloured photographs do have their own charm as nostalgic artifacts, so it’s worth finding out who applied the makeup.

Content wise, the pictorial evidence presented is one in which flattery, in the form of cosmetic change via retouched negatives and colourised prints, and an emphasis on fashion and glamour by women photographers could be a stronger theme than children and family life in New Zealand’s past, while the grittier and fascinating human stories of hardships and determination to make use of photography for work or recreation are mostly evident from the written records.

Like everybody engaged in historical research today, Mitchell made good use not only of New Zealand’s Papers Past online but also other new online sources such as genealogical databases like Ancestry to discover and confirm identities, relationships and additional lines of investigation.

The result of her ongoing investigation which included interviewing living subjects over a number of years and collecting rare, authenticated examples of the work of early women photographers are what make her book such a valuable resource and springboard for future researchers. Hopefully her book will itself be republished on the internet for those who enjoy distinctive images made from all corners of the world.

John B. Turner, May 2024

Lissa Mitchell is the Curator of Historical Photography at The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington and has held previous roles in photographic collection management and preventive photographic conservation roles at the New Zealand Film Archive (now part of Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision) and the National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa. She has a degree in art history from Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington. Prior to a career in photographic history, Lissa was an experimental filmmaker.

John B. Turner. Born in New Zealand in 1943, Turner comes from a background in the printing industry. He worked as a news photographer, and mural printer before joining the Dominion Museum as their photographer and unofficial curator in Wellington. before moving to Auckland in 1971 to join R D (Tom) Hutchins (1921-2007) as a lecturer in photography at the Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland. He was the founding editor of PhotoForum magazine in 1973 and had already started curating exhibitions of historical and contemporary New Zealand photography. Among his books and catalogues he co-authored with the late William Main, the anthology New Zealand Photography from the 1840s to the Present (1993). Upon retirement in 2011 he moved to China to further his research and promotion of Hutchins’s extensive photo essay on China in 1956; an exhibition and catalogue of which launched at the 2016 Pingyao International Photography Festival. That same year saw the launch of Recollections of a Distant Shore: New Zealand Chinese in Historical Images, an exhibition and book co-authored with Dr Phoebe Li for showing in Beijing and New Zealand. Photoforum Inc continues to promote fine photography through its book and online publishing (www.photoforum-nz.org) during its 50th year and recently featured Turner’s 10-part blog series ‘New Zealand’s photo treasures heading for the tip?’ An investigation into the non-collection of analogue photographs by government funded heritage archives.

Through Shaded Glass: Women and photography in Aotearoa New Zealand 1860-1960 by Lissa Mitchell. Te Papa Press, Wellington, New Zealand 2023. ISBN 978-0-9951384-9-0. NZ$75.00. [email protected]