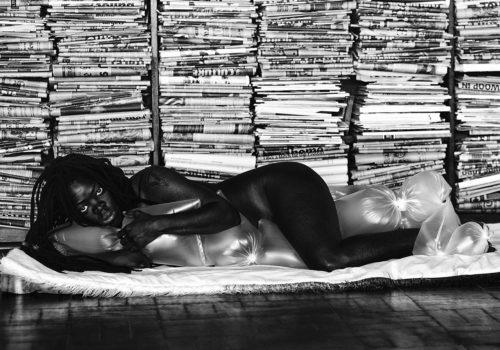

It is the long-awaited return of Zanele Muholi to the Tate Modern. The artist’s first major retrospective in the United Kingdom – initially inaugurated in 2020, it was interrupted due to the lockdown. It is therefore four years later, in a revised and expanded version, that the exhibition returns to the London museum, after a successful European tour.

“My mission is to rewrite the visual history of South Africa for Black queer and trans people, so that the world knows about our resistance and existence in the face of hate crimes in South Africa and beyond.” These powerful words from Zanele Muholi open the exhibition and set the tone. Activist-artist. Artist-activist. Two inseparable entities, intimately linked for Muholi who calls herself a “visual activist.” Because beyond aesthetics, what matters most in photography to her is the content: who is in it, and why?