Let’s start with the exhibition “Alternative Visions: A Female Perspective.” What is its genesis?

In 2017, I was invited by the T3 Photo Festival to give a lecture on the Western perception of Japanese photography. I was quite surprised to see how interested the Japanese audience was in this topic. Then Ihiro Hamaya, the festival director, contacted me to imagine an exhibition for the fiftieth anniversary of MoMA’s “New Japanese Photography” exhibition. This is an exhibition I’ve been deeply interested in over the past few years, in my exploration of post-war Japanese photography. The idea wasn’t just to celebrate an anniversary but to retrospectively examine this exhibition, its influence over time, and to deconstruct its various elements. The exhibition was curated in a very particular way: it aimed to summarize Japanese photography through 15 artists at a time when information was not easily accessible. Not only 15 artists, but 15 contemporary, mostly young, artists.

However, there were gaps and omissions.

Yes, I wanted to focus on what wasn’t shown at that time. I proposed two concepts. The first was based on the fact that there were no female photographers among the 15 presented. So, the idea was to create an exhibition focusing on female photographers active at that same time, who could have been considered. The goal wasn’t to find completely unknown artists but rather artists who were already published in magazines, had already produced a book, or had exhibited, artists who, in some way, existed in the photographic world of the time.

Why were there no women in the MoMA exhibition?

The photography world in Japan was completely male-dominated. Sayuri Kobayashi from the Tokyo Museum of Modern Art conducted research on the list of professional photographers registered with the Japanese Professional Photography Society. In 1966, only six out of more than 400 were women. By 1974, only 27 out of 950.

However, some female artists had been featured in Camera Mainichi, edited by Shōji Yamagishi. What we don’t know, or at least what I don’t know, is to what extent John Szarkowski and Shōji Yamagishi, the curators of the MoMA exhibition, considered these women’s work less significant than that of their male counterparts. There were quite harsh criticisms at the time, especially in the U.S. Given the social and political context of the 1970s, it’s hard to imagine they didn’t think about it.

Among the six artists exhibited at the T3 Photo Festival Tokyo — Hisae Imai, Tamiko Nishimura, Toshiko Okanoue, Toyoko Tokiwa, Hitomi Watanabe, Eiko Yamazawa — was one of them as dominant as Moriyama was in his time?

What’s quite striking is that all these artists were very different from one another. They represent an impressive diversity of practices. At that time, these photographers had often only completed a single project, a book, or an exhibition. They hadn’t been able to start a full-fledged career, and these projects had probably taken a colossal effort to convince a publisher to release a woman’s book on a subject. The comparison with Moriyama isn’t possible, and let’s remember that in 1974, Moriyama had only one series presented despite his quite diverse body of work, unlike Shomei Tomatsu. In our exhibition, Eiko Yamazawa may be the only one who was starting to establish a more robust career. She had traveled to the U.S., worked with a prominent American photographer there, then opened a photography studio while playing a role in education and becoming a figure in the photography world, encouraging many women to take up photography.

Were artists like Toshiko Okanoue or Hitomi Watanabe able to make a living from their work in 1974?

These are two different cases. The series Watanabe exhibited captures the student protests of 1968 and 1969 in Japan, some of the most violent protests in modern Japanese history. She began her studies at the Tokyo College of Photography in 1967. Watanabe began photographing in the 1950s but stopped all artistic work after getting married… It was over.

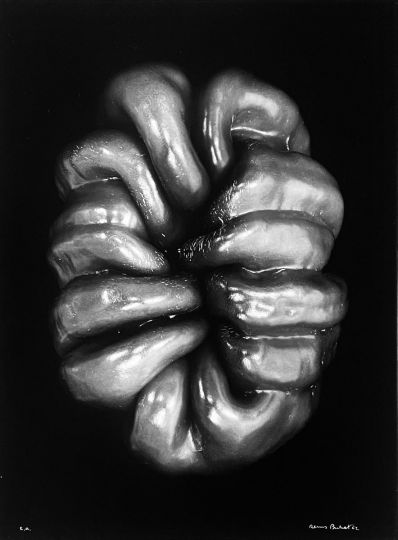

Can you tell us more about Okanoue’s work, which is closely related to surrealism?

She fully embraces surrealism as an influence. She’s not the only one in the exhibition, along with Hisae Imai. Japan has always been very interested in artistic movements that originated abroad. It has drawn a lot from what was happening in the West, whether in Europe or the U.S. Even when the country was closed off, there was always a desire to understand what was developing elsewhere. Photography is a prime example. Okanoue was closely tied to literary surrealism. She’s not a photographer — she doesn’t create her own images, but rather uses existing ones, drawn from Western magazines like Life or Vogue. Her works often deal with the image of what a woman should be as conveyed by these magazines. Today, many artists don’t create their own images but use existing ones. But in Japan at that time, it was a unique approach.

What’s the second project you’ve developed with the festival?

The other exhibition stems from another observation. The MoMA’s “New Japanese Photography” didn’t feature or barely featured any books. Yet, the photographic book was absolutely central in Japan at that time. I came up with the idea of creating a reading room, to showcase the books of the series exhibited in New York in 1974. I say books, but also magazines, which were crucial at that time. The majority of the books come from the extraordinary collection of Isawa Kōtarō, a great collector of photographic books and founder of the magazine Déjà vu. He’s now the owner of Kawara Coffee Labo, where much of his collection is freely accessible for reading. The book is meant to be consulted; no matter how precious it is, the reader should be able to take hold of it, turn its pages, browse it, and explore it rather than see it as a fixed object.

We’re also presenting in another room the new editions or facsimiles of these original books that have been published in recent years.

More information