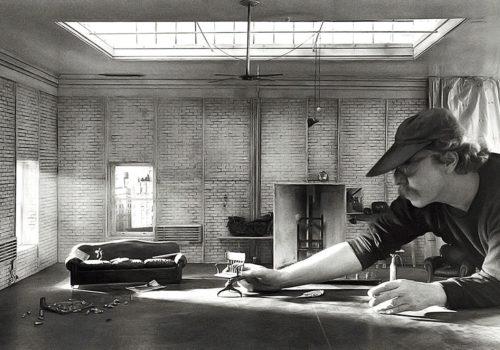

Last April, we showed you some photos of Charles Matton, this jack of all trades of genius who died in 2009. Sylvie, his wife offered us this film which she made after he disappeared. A pure marvel, which she accompanies with these words.

JJN

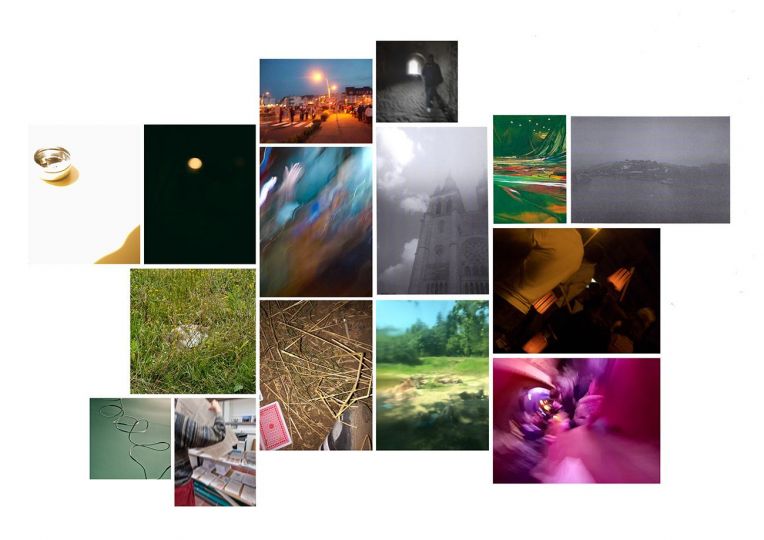

Charles had a film project with Arte which would narrate his work, which would reveal both its complexity (through all the mediums used and its various approaches to appearances) and its coherence. He would have filmed a lot of his works and other images too, he was already imagining sometimes ultra-fast editing, a kaleidoscope of visuals which, colliding, would give us to see and understand. But cancer got in the way. A few days after his funeral, at the end of November 2008, Jérôme Clément, then president of Arte, said to me: “You are going to direct this film”. He didn’t know that he was offering me not only the possibility of recounting the artist Charles Matton, but also the most improbable and sumptuous of catharses. An incredible privilege.

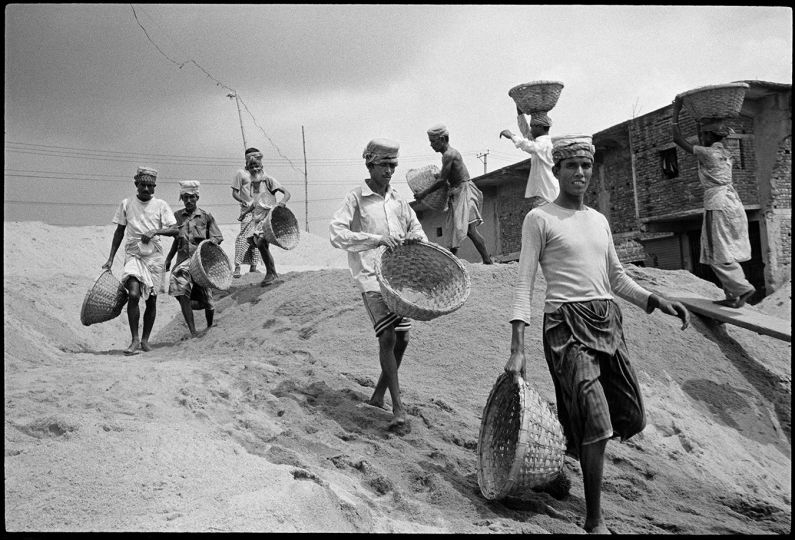

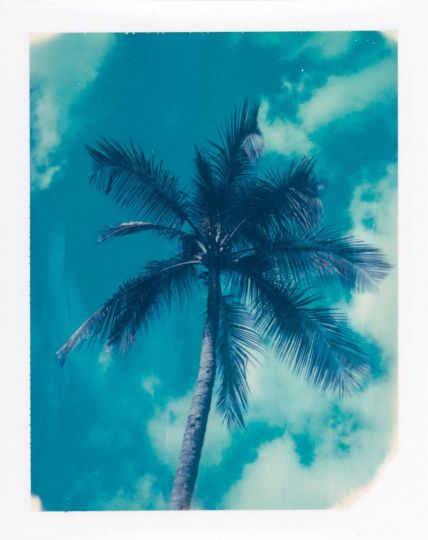

With the Avid system installed in the studio at the beginning of January 2009, I worked for nine months on this film. There was no question of filming, apart from a few missing shots in the story, because very quickly it was understood: that always, since the 1950s and the acquisition of a camera, Charles had photographed and filmed, the surrounding life and his creative work. In black and white and in color. As if he had always worked on the preparation of this film. I worked alone for three months organizing the editing “bins”, finding, choosing and classifying all the films, old and more recent, professional and personal, those I had in mind, those I rediscovered, including the precious 16 millimeter reels dating from the 1950s, found in the cellar; to prepare the images to be scanned, Ektachromes and opaque documents by searching through thousands of photographs; to imagine and to prepare the various sequences imposing themselves in a consistent unfolding, like so many evidences.

Three months during which, clouded in immense grief and an abysmal absence, and propelled at the same time into a past that was most often common to us, I saw and heard Charles on three screens all day and night until some god forsaken hour. I wrote down his sentences unfolding and complementing each other from one interview to another, rediscovered in images or sounds moments of our life together over thirty-two years, years of energy and joy, I also marked the future cut after a dazzling smile. It was as if a thread stretched between the filmed image of Charles, so alive, often joyful, and me scrutinizing him during those long nocturnal hours, waiting for the ideal phrase, as if this taut and fragile thread never had been broken, never would break. Thanks Jerome!

Then, the editing really started with the marvelous editor and friend Yves Deschamps, after a first leap into the void (“What do we start with?”) and took place for six months. Yves arrived in the morning around 9 a.m. and left around 7 p.m., often later. He is a work addict; but by his side it is easy to understand why and how much being a film editor is to exercise the best job in the world. Sometimes we went out for fresh air in good weather and had a quick lunch on the terrace in front of my house. But often we ate in the kitchen, wasting no time. Faced with the three Avid screens, while Yves found the best links and practiced the magic of sound editing like no one and for my greatest pleasure, I never took my eyes off the screens to react, learning to detect, to listen, and to trust my feelings (“It’s only about that”, said Yves.). At his side, a colander on my knees, concentrated in front of the screens, I peeled green beans and shelled peas – great never told common memories, which we still sometimes remember.

The film was built little by little, from one brick at a time. A family and clan adventure, with our two sons: Léonard, then 24 years old, filmed the few missing shots and sequences, including those in Saint-Honoré-les-Bains in the childhood home, to be mixed with shots filmed with the family ten years earlier. He was also the one who read passages from a Charles monograph to make up for his missing father’s voice on crucial topics. Jules, 20, who had not yet left for New York to study composition at the Juilliard School, composed the original music for the film. The other musics would be that of Charles’s films, and in particular those, magnificent, of Nicolas Matton, his second son, composer for the films The Light of Dead Stars and Rembrandt. And it is Isabelle, Charles Matton’s assistant for twenty years, who, generously watching over the smooth running of the film adventure, who exhumed from the cellar the films whose disappearance saddened me.

I can only share here these few anecdotes or deep feelings. The rest was just work and pleasure. What is certain is that, holder of the moral rights to the work of Charles Matton, as well as all these documents, films, photographs and soundtracks, witnesses of the life and work of a man who always gave esthetics to ethics, of such a poetic man, always moved by a fair and honest reflection, the thought that constantly animated me during these nine months was very simple: guardian of all these treasures, of all these vibrant documents , these marvelous traces of life and creation – personal and professional memories nourishing each other, intertwined and linked by cut or fade out, commissioned to reveal the story of Charles Matton’s life by himself and his works, I had no right to screw up this film. I hope to have averted this danger during this realization.

Sylvie Matton