In 1937, a new magazine was launched in the UK. Though small in size, fitting into a pocket, it would have a tremendous impact. Lilliput, founded by European Hungarian émigré Stefan Lorant (1901- 1997), was the first British magazine to publish an impressive roster of international photographers, including Erwin Blumenfeld, Herbert Matter, Willy Ronis, Brassaï, Pierre Jahan and Ergy Landau. It published a series of now-famous reportage by Bill Brandt, including Wapping and Halifax, and then there were the humorous juxtapositions on double-page spreads, pairing Neville Chamberlain with a llama for instance. Articles and short stories were provided by authors such as Somerset Maugham, Upton Sinclair, Ernest Hemingway, George Bernard Shaw, Robert Graves, Georges Simenon, and C.S. Forester. Walter Trier provided covers, and for the first 147 issues they featured a man, a woman and a Scottish Terrier.

Stefan Lorant sold Lilliput to media magnate Edward Hulton in 1938. That same year they launched the extremely successful magazine Picture Post. The vast Picture Post archive is preserved at Getty Images Hulton Archive in East London. I spoke to Matthew Butson, the archive’s vice president, about Stefan Lorant and began by asking him about Lorant’s life and career before he arrived in the UK in 1933.

Matthew Butson : He was born in Budapest, of Jewish parentage. In 1919, he moved to Germany, where he launched an incredible career as a photographer, journalist, magazine editor and filmmaker. The Life of Mozart was the first of 14 films he made in Germany and Austria. He also claimed to have given Marlene Dietrich her very first screentest. While he didn’t hire her, they remained friends for years and years. He cut his teeth as a magazine editor at Münchner Illustrierte Presse, one of the very best picture magazines in Germany.

His career in Germany was cut short by the Nazi takeover in 1933.

Matthew Butson : He had been highly critical of Hitler in print and was imprisoned just six weeks after he came to power. He wrote a book about the experience, I Was Hitler’s Prisoner, published in the UK in 1935 and it became immensely popular. It’s a great read.

It’s quite linear and it doesn’t go into massive detail about the politics of the world at the time. It’s about his incarceration. When you read it, you get the impression that he was imprisoned for years but it was only about six months and then he was released. He made his way to the UK via Paris. I can’t help thinking that had he been arrested and imprisoned by the Nazis five or six years later, it’s quite likely that he wouldn’t have survived. The sad part of the story is that when he first arrived in the UK, he was registered as an enemy alien, despite him being Hungarian, not German.

He started his career in the UK as editor

of Weekly Illustrated, launched in 1934 by Odhams Press. It introduced a European sensibility to British picture magazines, which would continue with his work on Lilliput and Picture Post.

Matthew Butson : His cinematic experience, and all the other expertise he had built up in telling stories, gave him a unique vision to create picture magazines. Lorant’s workload was immense. He was editing all three magazines as well as working on other publications in the Hulton stable. He was like a man obsessed with telling great stories. Picture Post had a real impact. It changed everything in terms of how we view pictures in terms of stories, and the world around us. I love that so many people think that the Picture Post masthead was copied from Life which had been founded in 1936. But Lorant knew Henry Luce, founder of Life, and I think it’s likely that Luce got the original idea from Lorant and that Lorant then “returned the favour” and stole the design back for Picture Post. The mastheads are virtually identical.

Looking through the first 10 years of Lilliput, the list of contributing photographers is nothing short of remarkable.

Matthew Butson : Yes, and it underlines his European background and that he knew all those photographers, essentially at the birth of the golden age of photojournalism. Life tended to publish American photographers in the early years so Stefan brought a completely different, very European sensibility to the world of picture magazines. The first photographers at Picture Post were Kurt Hutton, Hans Bauman and Tim Gidal, all immigrants, and a few British photographers, such as Humphrey Spender and Haywood Magee. In addition, photographs were bought from various agencies. They were only paid if the images were published. Back then, nobody asked for the return of prints as they were deemed to be worth only the paper they were printed on. That’s why the Hulton Archive has such a vast number of vintage prints on file. Just the other day, we found some wonderful André Kertész prints that had been sitting in our files for decades. Used or not used, they all went into the library, which had been created by Stefan Lorant’s brother Imre, and in honour of him, and Stefan of course, our darkroom here at the archive is called The Lorant Darkroom.

Lilliput was immediately recognisable, thanks to the Walter Trier covers, always featuring a man, a woman and a Scottish Terrier.

Matthew Butson : Trier was an incredible talent and just so ahead of his time. He created the covers until 1949. After that, he went to the US and I don’t why he left the world of picture magazines behind. Instead, he decided to focus on books.

In addition to picture stories, by Bill Brandt among others, a large section featured the famous juxtapositions.

Matthew Butson : The juxtapositions were a masterstroke. They were always completely unexpected, full of imagination, like placing a racing car opposite a hippo.

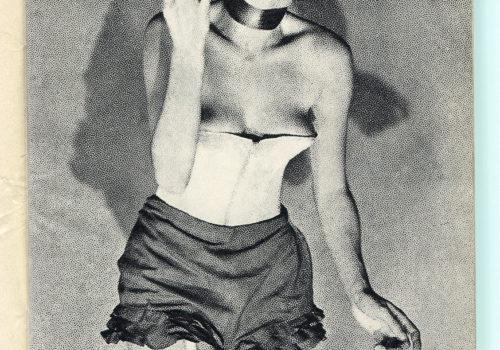

A lot of what Lorant did at that time really inspired a lot of graphic designers. Lilliput was very cleverly put together. It published writers like Hemingway and Upton Sinclair and all these people. There were serious elements, comic elements and as a gentleman’s magazine, there was also artful nudity by real masters such as Erwin Blumenfeld.

Lorant and Edward Hulton co-founded Picture Post in 1938. They were very different people. Lorant, left-leaning, Hulton, arch-conservative. There must have been conflicts and bust-ups.

Matthew Butson : Oh, there were! A prime example is the very first cover of Picture Post. Hulton, always angling for his knighthood, insisted on having two battleships on the cover, to show the might of the British forces. Lorant said yes, yes, but he had no intention whatsoever of putting two battleships on the cover, opting for two leaping cowgirls instead. Hulton was absolutely furious when he saw the cover! But he changed his tune when he saw the circulation figures. 100000 copies had been printed initially but within days they had to print another 500 000. Picture Post was a roaring success. From then on, Hulton bit his lip but his editorials in Picture Post continued to be filled with his right-wing bombast. While they were often at loggerheads, they still managed to work together.

In 1940, Lorant left the UK and settled in the US. Why did he leave?

Matthew Butson : It was partly because his application for British citizenship had been turned down, partly because in 1940, it seemed more than likely that the German forces were going to invade the UK. Having been imprisoned once by the Nazis, he didn’t want to repeat the experience.

Despite Lorant leaving, Lilliput and Picture Post retained their identity, up until 1950, but then things began to change.

Matthew Butson : After Lorant left, Tom Hopkinson took over as editor for Lilliput as well as Picture Post. If anyone was The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, it was Tom Hopkinson. He was almost Lorant incarnated. He could be gruff, hard, and difficult but he had a vision that mirrored Lorant’s vision, particularly on social issues and he leant towards the left. But in 1950, Hopkinson left the Hulton group, after a dispute over a damning story that Bert Hardy and James Cameron brought back from the Korean War. Hulton was angling for a knighthood and wanted it watered down. Hopkinson was either fired or left in anger, perhaps a bit of both. The Korean story was published but with all the criticisms of the UN and Western powers removed. With Hopkinson gone, Lilliput and Picture Post lost their way. Editors came and went, in truth, they were managers rather than editors. The two magazines started emulating their competitors, featuring Hollywood stars and personalities. Picture Post was crushed by the arrival in 1955 of ITV, the UK’s first commercial TV channel. Advertising revenues collapsed and Picture Post folded in 1957. Lilliput stumbled on for a few years. In 1960, it was incorporated into Men Only, a pornographic magazine. It’s a real shame that Picture Post disappeared. Just think of all the amazing reportage it could have published during the swinging sixties and all the political turmoil and cultural change that took place.

You met Lorant a number of times. What was he like?

Matthew Butson : I met him towards the end of his life when he was in his nineties. There’s only one way to describe him and that’s absolutely exhausting! He would talk and talk and talk! It was all about Stefan. He had a real ego. To me, however, that pales into insignificance when you think of the works he left behind, the German magazines, the films, Weekly Illustrated, Lilliput, Picture Post, the books he produced after he had settled in America, the biography on Lincoln, the book that W. Eugene Smith contributed to, Pittsburgh – The Story of an American City. He left a real mark and here we are some 90 years later talking about him.

It kind of begs the question; would Picture Post have come into being without Lorant? Would the Getty Images Hulton Archive exist without him?

Matthew Butson : I think the archive would exist in some form but there would be a lot more press and feature material. But the Picture Post part is the heart and soul of the archive. It’s not the earliest, not the latest archive in our holdings but it spans that golden age of photojournalism. Picture Post just captured the zeitgeist of the times, the run-up to war, the storm clouds that were gathering. Hulton would probably have produced some sort of picture magazine but without Lorant, it would have been something very different.

Text and interview by Michael Diemar

Article first published in THE CLASSIC Issue 11.

The magazine is available to download at :

https://theclassicphotomag.com/