The Eye of Photography pays tribute to American photographer Stanley Greene, who died of illness on Friday, May 19, 2017 in Paris. A homage by curator and journalist Christian Caujolle.

Completely flawless. Until the end. Not even your illness, which sapped your strength and, as you well knew, would end up defeating you, ever managed to crush your spirit. Your great feat was to take off without having aged, apparently unmarked by time, with elegance that was always yours. You took your leave in your prime.

For, in addition to your beauty, your bearing, and your voice, deep and hoarse at the same time, and all the other physical elements that made you an immediate center of attention, you had this: absolute elegance. Elegance of gestures: your slender hands that knew how to wear large rings; elegance of feelings: often withheld despite their intensity, sometimes until you exploded.

In order to relieve some of the pain, grief and sadness revive memories. Memories we shared and those you told us about, modestly, but also with determination and full responsibility. The first shared memory is of you bursting onto the Parisian scene, where you emerged through your fascination with Brassaï and your interest in Doisneau. You cultivated a vanishing Paris of cafés in black and white and as a client; this was what brought us together around a text at the time of your first exhibition. Impossible to recount all the memories, and some must be set aside as poultice, but it is essential to share others. The memories of Agence VU’, of the moment when you – you who had dabbled in fashion and, as a young man, covered the alternative rock and punk music scene – decided it was time to do away with nostalgia and frivolities. You no longer enjoyed images of Paris because you knew they were pointless. And even though it’s impossible to tell whether you had become one day what one calls a “photojournalist” – since whatever label one tries to pin on you will definitely be off the mark – you decided to bear witness to the world and its suffering, which was also your own and fed your rage. Because the unthinkable had happened, because the Berlin wall crumbled, because the world would never be the same again, you decided to devote your life to testimony, to exploring whatever troubled you, unsettled you, or seemed either unusual or unacceptable. The decision to document the Caucasian countries when no one was interested in them and no magazine would pay for a single roll of film, brought you to Chechnya. When a few months later the country was invaded by Russia, plunging it into a long war, you were the only reporter to have images of this small Muslim republic. And it became your second home.

You were driven by a sense of commitment, more than that, by a mission, and by passion. Having reviewed, edited, and discussed them with you so many times, I can’t help but think of those contact sheets which tell your story and your worldview better than anything else. They show an unwavering, visceral sensibility, and an ability to go, in a blink of an eye, from a posed portrait to a snapshot of a fighter in mid-combat, to a contemporary pieta, with characteristic freedom. Freedom to decide for yourself, freedom to look at the world the way you feel, and freedom to own an intense emotion that could have well made you headstrong. The contact images of the attempted coup against Boris Yeltsin’s in 1993 would always send a chill down my spine. I was afraid for you, afraid that you might have – should have – been gunned down, oblivious for an instant. As I confronted my retrospective fear, it was you who would always reassure me.

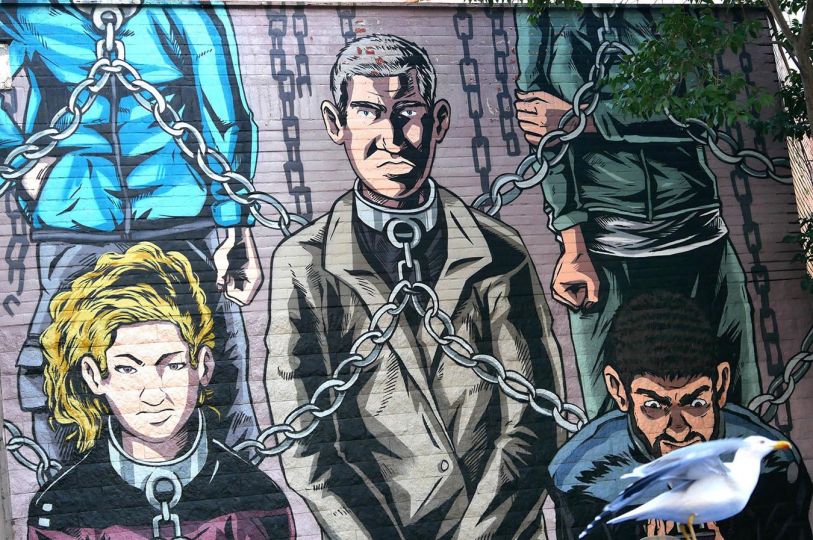

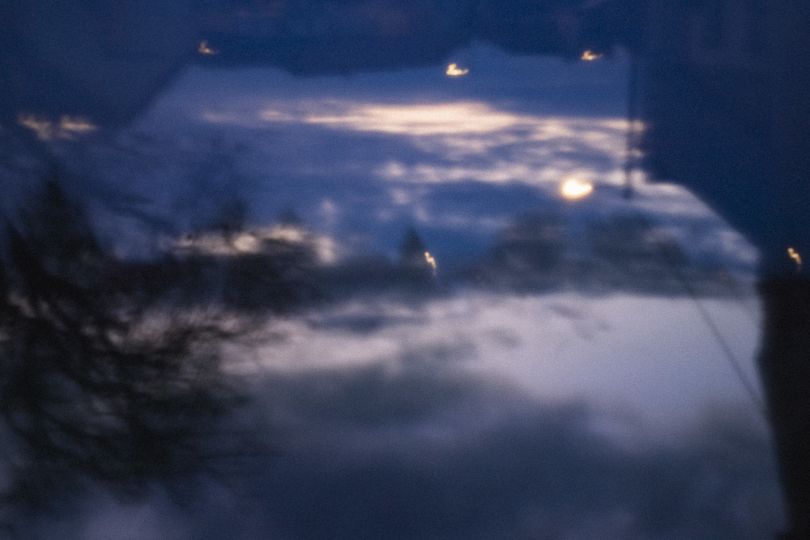

Images in the press and in exhibitions, at festivals and in galleries, in books, down to the last detail, from the captions and the texts to the choice of paper, along with all the doubts, radical decisions, and errors we’d have to acknowledge later as a way of doing, certitudes that allowed you to move on, certitudes about values as well as situations: all these images are there and they will remain as a gesture of which you are the sole author, as well as an actor. I needed time, beyond friendship and respect I had always felt toward you, to understand that the fact you had dedicated the better part of your life as a photographer to capturing conflicts and dramas was, at the end of the day, a form of going back to your youthful engagement and bridging the Black Panthers and anti-Vietnam war protests. There is, in all this, an extreme form of generosity that you shared brilliantly and with a great flair amid discomfort. You never complained, even when you were angry or disagreed; you always pushed forward. Many of your images, especially landscapes, are imbued with romanticism; in some scenes of war there is tenderness; and some portraits emanate with love.

Suddenly Kertész comes to mind – we talked about him a lot and could never agree – toward the end of his life he said, “I’m too sentimental.” Stan, you’ve always been sentimental and it’s a wonderful word when it comes from a vital necessity to be honest with oneself because one must be honest with others.

Stan, with all my love,

Christian Caujolle

An independent curator, Christian Caujolle worked formerly as director of photography at Libération, founded the agency VU’. He also teaches at the École Nationale Supérieure Louis Lumière in Paris.