Sarah Pickering is a British photographer who researches truth versus verisimilitude through the medium of photography, though never manipulating her images. This week, she presents her series about forgeries, “Art & Antiquities”.

“One of the Photography curators from the V&A got in touch with me and told me that I would enjoy the exhibition put on by the Metropolitan Police at the museum. It was an educational show that had all kinds of evidence from the police archive of different sorts of forgeries and there was an area devoted to Shaun Greenhalgh. It was a recent and sensational case because he had spent 19 years without being caught. There was no real investigation into what he and his family were doing during the 19 years so he just carried on and got more and more audacious and indignant about the mechanisms of the art market.

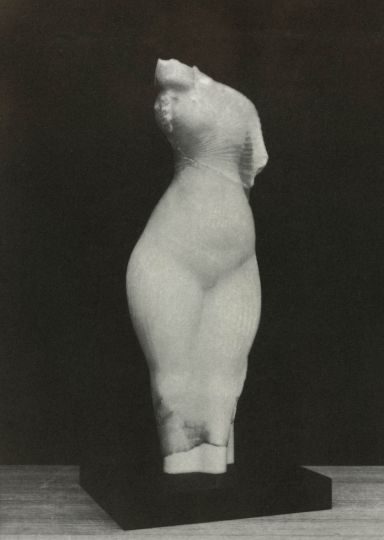

In a corner of the show the curators and police tried to give a sense of what his workshop was like. However I later saw footage that the police recorded of what they found when they raided Greenhalgh’s house. The shed was full of rubbish and it looked like he hadn’t worked there in 5 years, and there were forgeries in progress all over the house. When I had a look at other evidence, as well as the forgeries themselves and materials to make them, there were a lot of items like checks, letters to and from experts, an auction catalog (used as proof of provenance), and I found a packet of minilab photographs that were shot to send to museums for valuations. Some depicted a version of the Amarna Princess whose head was the wrong size. The one that he finally sold had no head; he chopped it off because he couldn’t get the head right. I really wanted to make a work about those photographs as well as a bunch of other things so I had to get into quite detailed negotiations with the police about which evidence I wanted to use. They didn’t let me use the negatives so I presented the forgeries photographed by him and scanned by me. I had an idea too that I wanted to make my own forgery. They had some shelves at the police storage and I started to shoot the artifacts in a kind of Fox Talbot style. Talbot was an Egyptologist, he could read cuneiform. When he was making progress with the invention of photography he almost put it to one side to concentrate on a book about Ancient Egypt. Had he been alive he also would have been able to read the spelling mistake on the tablet that caught out Greenhalgh when he presented it for sale to the British Museum, so there was a kind of connection there. And also Roger Fenton worked for a while cataloguing the collection at the British Museum, in a series of salt prints. So there was a genuine kind of precedent that these objects could, if they had been made at that time, have been photographed by Fenton or Talbot. Then I donated my salt print titled Egyptian Princess, Museum Collection. Salted Paper Print circa 1852-60. Unknown Photographer to the V&A museum and they loaned it back to me. So I could say it was part of the V&A museum’s collection though it is actually a ‘forgery’.

I also wanted to play around with the idea of what was invented and what was the original. So when I was shooting, I borrowed a shed and recreated the shed as it was recreated at the V&A museum. So there was this kind of slip in that I have restaged the same objects in the scenario that was set up in the museum, and neither was authentic. So there are all these levels of removal from an original. This all gave a sense of not being able to penetrate what the truth is. To me investigation and archive are intrinsically connected with photography. There is a connection between photography and an idea of authenticity and there is also a connection between the idea of an original and a reproduction.

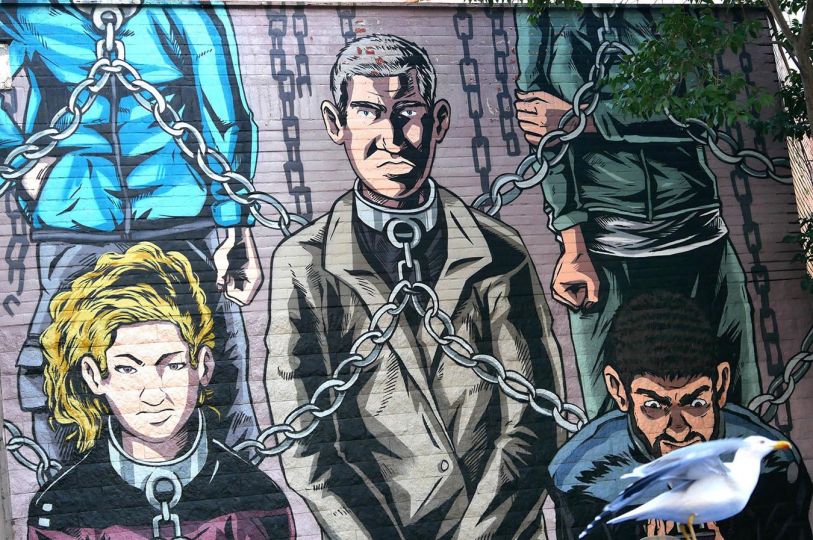

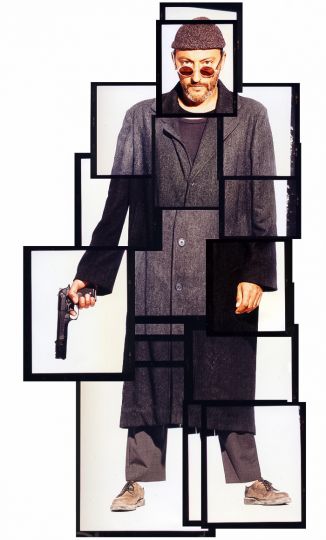

While I was investigating the Shaun Greenhalgh story I managed to find out about a TV program that had been made about him. I was fortunate enough to get in touch with the company who made the program and the prop maker had all the props still that he had made for the program and he agreed to loan them for the exhibition. So I was able to show them alongside the photographs of the evidence that I made in the police secure storage room. I also bought six books about Gauguin’s Faun. Some are still in print, and we can still buy them. The Faun was a forgery made by Greenhalgh and it is so embedded now with Gauguin’s history. It was nice to extend my practice beyond working with photography to working with photographs within a book and not feel that I have to rephotograph the book. I also made silver gelatin prints that look like installation shots but they are actually my works. I wanted to complicate the way photograph can been seen, mainly as a response to what a notion of authorship was, and also to look at some of the modes of existence photography has.

There are all kinds of parallels between the aura of an artwork and the aura of an artist. For instance there was a Channel 4 TV program about Gauguin that is presented by Waldemar Januszczak, an important art critic who enthused about the Faun (which wasn’t known as a forgery at the time). There was a big exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago and he was so excited about this work, saying how important it was in Gauguin’s career, and how it reflected his sexuality, his anxieties and his creative impulses. So there is all this external material and investment that is overlaid onto the artist. That really fascinated me because when it all falls apart and you find out that a work is actually a forgery, where does it leave these words? I guess they should go to the forger, but the forgery can’t ever exist without the artist or style that’s being emulated. Going through the evidence, my relationship to Greenhalgh developed into a kind of admiration and I was very excited by this character from an artist’s perspective. For the police he is obviously a criminal because what he did is illegal, but what was interesting in my position was to appropriate his works and also make my own forgeries, as a way for me to springboard from his story as he did with other artists. ”

Sarah Pickering