All the new media, including the press, are art forms which have the power of imposing, like poetry, their own assumption,” Marshall McLuhan observed. We live in a time when new media is so ubiquitous as to be omnipresent and the only escape from the world we’ve built is to be out of satellite range—or, even more difficult, to simply turn it off.

But we don’t because we won’t because, like the greatest pharmaceutical drugs, new media has rewired our brains to change the way in which we perceive ourselves and the world itself. The way in which we live has become so extreme that we are hard pressed to remember how we operated any other way. We take for granted the way in which these interactions create and define experience, allowing ourselves to fall under the spell, whether we want to or not. At a time when to not have a Facebook account is an act of defiance, we must consider the bigger picture—the machine itself.

Gingko Press has just released The Book of Probes, a collection of Marshall McLuhan’s finest words culled from his books, over 200 of his speeches, his classes at the University of Toronto, and from nearly 700 shorter pieces he published between 1945 and 1980. The book has been designed by the renowned David Carson, and is aesthetically divided into two sections. One section features quotes, set against the traditional white background. This section is understated, simple, and easy to grasp. It allows the words to do the work of words, and requires nothing except our focused attention.

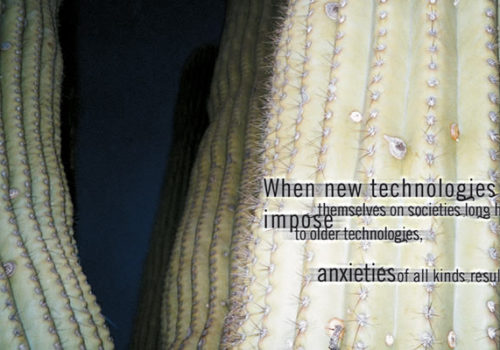

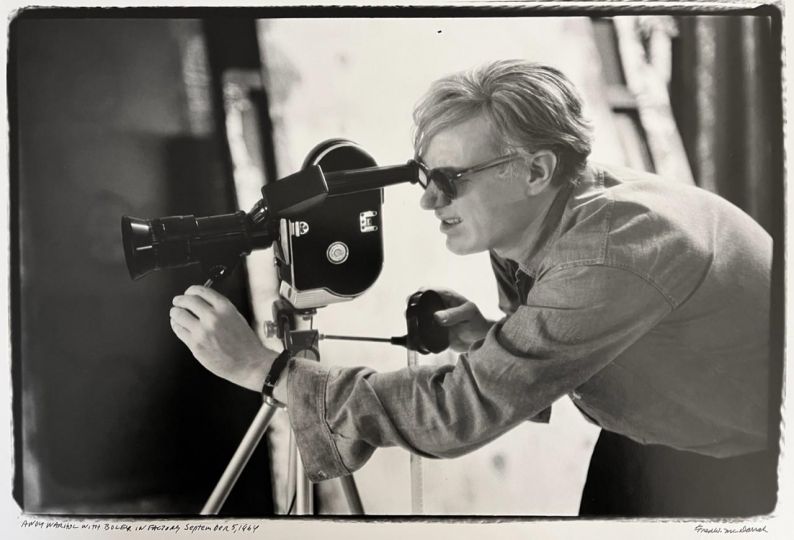

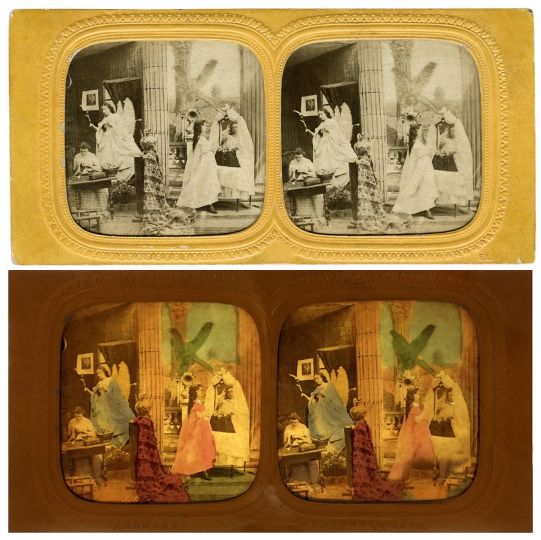

What makes The Book of Probes fascinating id the other section, the one in which Carson interfaces with McLuhan on a dynamic level. Here, McLuhan’s words are set against a graphic, a photograph, or an illustration. The spread becomes a synthesis of image and text, where the font and layout of the words change the energy of the image upon which they lay. The written word takes on an aesthetic dimension, conveying in equal parts meaning, spirit, and energy. Meanwhile, the image no longer serves as images traditional do, it does not offer reportage or meaning on its own terms. Instead it serves as a vehicle for the words themselves, fusing with the spirit and the energy of the greater thing, the Idea as Ideal.

One of the most challenging aspects of the photography book is the use of words. Words, so dominant in our culture and our society, demand our attention in the way nothing else quite does. They are perceived by the eye and translated by the brain. They are a series of symbols that mean different things depending on the way in which they are ordered. The more evocative the order, the more compelling the idea, until something clicks inside us, and the words stop being words and start being “real.”

When images appear near a photograph they are taken as something greater than words. They are taken as interpretations of the thing which we are viewing. We either read or resist, we want to know or we don’t. We trust our perceptions or we give them over to another to define our experience for us. The challenge of great photography books is how to find the balance between the image and the text, the way to provide information and context without altering our visceral experience of the image itself. Words should be used to provide support, but all too often we become lazy and allow the words to pull the cart.

The Book of Probes is powerful because it addresses just this issue, with words that comment on the experience as we are living it. Taken on their own, McLuhan’s observations are essential to cutting through the fog and the haze of cultural complicity. His insights force us to question our assumptions about the way we communicate, the way we connect, the way we create meaning through media today.

“Obsolescence is the moment of superabundance,” he notes, making us think about why print took such a sharp nosedive, a decline from which it may never recover. In the world of photography books, that superabundance was all too obvious. With the transition to digital production at the same time that China grew in the print industry, costs declined so dramatically that the publishing model of producing more for less did itself in. While publishers were focused on producing cheap product, no one was talking market share or audience building. Instead publishers stood back as superstores killed the retail industry, only now to be terrorized by the power that Amazon wields. No small thing the company named itself after the great rainforest and the great woman warrior. Did publishers really think they stood a chance against a business model that took advantage of their short- sighted thinking?

McLuhan’s single quote in a book of 576 pages stands out to me, but that is only because that is the spread to which I flipped as I write this story. Turn another page and there is a question McLuhan poses. “What happens when the ad makers take over all the popular myths and poetry?” What do you think? What do you feel? We all live in a world where advertising has become culture and culture has become advertising and it becomes very difficult to distinguish the line between art and commerce. That is—if there ever was one to begin with.

The Book of Probes is, in many ways, the ultimate objet de McLuhan. It forces us to stop rushing from end to end, to enjoy the means and the journey instead. It asks us to contemplate and consider rather than conclude. It suggests that the answers do not matter as much as the questions do.

Sara Rosen

The Book of Probes

Eric McLuhan, David Carson

576 pages

Gingko Pr Inc; 1 edition (November 2003)

ISBN-10: 1584230568

ISBN-13: 978-1584230564