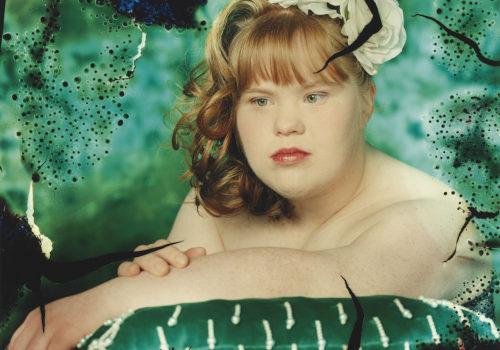

British-born photographer Sam Harris is best known for his body of work “Postcards from Home”, through which he has demonstrated a unique approach to turning family photographs into a visual narrative that appeals to those outside the family circle. But his journey to this point has been one of hard truths, dogged determination and ultimately personal discovery, as he tells Alison Stieven-Taylor.

Postcards from Home (2008-2011), the first of a series, has been published online and is also an award-winning book, which has found wide appeal across cultures. “I think it is a common truth that if something is intimate then it is pretty universal really. I am sure Fellini said something along those lines,” he laughs. “Beyond that I guess the passion and the love that comes across in the photos is maybe refreshing when there’s so much sex, drugs and war photography out there”.

Harris, who now lives with his wife and two daughters south of Perth in Western Australia, began his career in London shooting bands for record covers. He says he came to photography through his interest in painting; he is another who originally wanted to be a painter, like renowned UK photographer Lewis Morley. “But I fell in love with the darkroom and the ability to play around with negatives and create images from my imagination. From the darkroom I took that into the studio and in-camera,” he says.

I know from my time as a music journalist that when you work in rock ‘n’ roll everyone thinks it’s so glamourous, celebrities and all that rubbish. They also assume you’re working in a hyper creative space, which was true in the eighties and nineties before the corporations saw dollar signs and gobbled up small labels. To quote from the series ‘Video Killed the Radio Star’ “when the marketing people got involved everything went to shit”. Harris agrees.

“When I started out it was about being inspired by the music. I’d come up with ideas, meet with the band and then create some kind of piece of artwork that would be used for the record cover. But I didn’t like making that kind of work to order and that’s where it was heading,” says Harris of his former life in London.

Bored with record covers Harris turned his focus to artist portraiture. The first magazine he shot for was the Sunday Times. “That was a lucky break and got things moving very nicely for me. I ended up doing that kind of work for the next decade. But niggling away inside my soul somewhere was the feeling that I was losing touch with the original artist in me”.

At the turn of the new millennium Harris was about to become a father for the first time. As he contemplated the future, lifestyles and babies he recalled an exhibition of Don McCullin’s work that he’d seen in London a couple of years earlier. “I remember that exhibition stopped me in my tracks, it blew me away. It made me very emotional. His work is so meaningful. I again started to question the work I was doing…it felt vacuous”.

One day riding the Tube he noticed an elderly couple sitting opposite. “They were a West Indian couple with matching denim shirts and jeans and white plimsolls and white cloth caps, just these twins. And I was like wow that’s such a great image. In those days I didn’t carry my camera with me all the time,” but from then on he travelled the Tube with his Rolleiflex.

Over several months he amassed a collection of images. “The next time I was at the Sunday Times Magazine office delivering a portrait job I said to the art director do you want to see some of my personal stuff I have been shooting on the Underground. I showed him, he really liked it and they ran a spread, which was fantastic. That was it, that pushed me and I started pimping myself as a documentary photographer,” he laughs.

As all documentary photographers know, work was sporadic, but Harris felt happy getting one good commission a year. He took assignments in Tahiti, Brazil and Australia and worked on defining his style. “It took me a few years as I was trying on different hats,” he says. “Only when I went and did a shoot in the Amazon for the Body Shop Foundation did I kind of realise some hard truths. When I was asked to go on that trip I was so excited. I was thinking this is like the dream job to go to the Amazon to shoot tribes in remote regions, it doesn’t get more classic documentary than that”.

“So I was really excited about going on that journey and I had some sort of romantic notion of painted faces and feathers and beads and all of this stuff. And when I got there of course what met me was very different, really kind of grim. They were in a really bad way and I was shocked by the conditions. That forced me to question my own involvement, what was I doing there? Was my photographing these people really going to help them from being wiped out? Is this really about my career?” Wrestling with these questions Harris headed home to contemplate his future.

Deciding to throw fate to the wind, he abandoned his career, packed up his then family of three and headed to India. As the trip rolled on Harris found himself gravitating towards photographing his family, and a rough idea around some kind of a visual diary began to unfold. At the same time he embraced digital for the first time, what he describes as “the never-ending polaroid, it’s brilliant”.

“You’d think that photographing your family is easy, but doing it in a way that is interesting outside of the family bubble, especially with small children, is actually really difficult,” he says. “I was trying to make images work, but I got to a point that I wasn’t really happy with it ultimately and I was struggling with my identity.”

Despite feeling like he’d boxed himself into a corner, Harris kept pushing. “It’s like that saying that to discover new land you have to get lost at sea. I’d lost sight of the land and when I realised oh shit I am actually lost, I was thinking what am I going to do now? But I just kept going and eventually that new coastline came into view and it was the beginning of Postcards from Home”.

The turning point came in 2007 when a photograph he took of his wife hanging the clothes out became an epiphany. That photograph captured “a moment between the moments. When I looked at that photograph it was like unlocking a key to the things that I was still grappling with. Suddenly I understood how to move forward with the way I was approaching my subject matter”.

Within a year he had the first incarnation of Postcards from Home, which was published in Burn Magazine. “You know I’d disappeared for years and no one knew what I was doing. Now I was going to be published in Burn with this personal project and I was petrified. In those early days of Burn there were very active conversations under the photo essays. And there was a lot of debate, and arguments and you could get shot down in flames easily. So I was very anxious, it was like starting again. But the response was wonderful and it grew from there”.

I ask him how his family feels about being the subject of a book? That kind of scrutiny must, quite frankly, get a bit irritating. He laughs. “I think that changes as they grow, and from week to week and month to month. So first of all my wife doesn’t really like to be subject matter so sometimes she is, but very rarely and on the periphery. We edit the work together and as soon as she sees anything that has a smell of her in the work she’s like ‘no’. But I’ve learned now and I won’t take the shot”.

“So I very much focus on my two daughters, but I am now letting friends creep into shots because we don’t live in a vacuum and as they get older those outside influences come in more so you will see with the second series – The Middle of Somewhere – hints of that and the third series, which doesn’t exist yet, will probably feature that more.With each series the concept evolves.”

He says his daughters, who are 14 and 9 years old, swing from being “quite proud, to being embarrassed. They only like pictures where they think they look good and that doesn’t always apply to the experimental shots. Some of the stuff I don’t show them, but their attitudes do vary”.

The challenges of documenting your family extend beyond teenage vanities and shifting moods says Harris. “You’re shooting in the same environment for a lot of the time so how do you avoid repetition, how do you find new ways to approach things? Also when you work at home, when are you on and when are you off? This work is spontaneous and a lot of it has to do with the light. Often that comes at the end of the day when as a family there are lots of things to do. But sometimes I have to step away from what I am doing and take a photograph and my wife has to be very understanding,” he smiles.

Multiple Publishing Platforms

As with many photographers Sam is exploring various avenues in the bid to get his work seen including Instagram, which has proven a worthwhile venture in terms of building an audience and gaining exposure.

Last year (2013) he was invited to take over the Instragram feed for The Photographers’ Gallery for one week. “I was really excited and honoured to do that. Instagram is a lot of fun, it gives you a chance to share images in real time with an active audience and you get to communicate with people all over the world…It’s a bit addictive,” he confesses.

After The Photographer’s Gallery he picked up “some very cool followers such as Kathy Ryan from the New York Times magazine, as well as curators and other galleries. I’m not in New York so I can’t go and see editors or curators, so for me it is definitely a good way of reaching people”.

As his number of followers increased so did his ranking. “One morning I posted a picture and looked at my feed and I had several hundred likes. Before that I was averaging around 30. I was thinking, what’s going on? While I was looking all these notifications were pinging in and I’d jumped from 350 followers to 800. I was perplexed until I received an email from Instagram saying congratulations we’ve selected your account to be featured as a suggested user. We think your work is unique and deserves a wider audience.” Two weeks later Harris had 21000 followers.

Harris says his passion to continue photographing his family is fuelled by a desire to capture the moments in his daughters’ lives that may ordinarily be missed. “As I witness my daughters’ transformation in what feels like the briefest of moments, I’m compelled to try and preserve something of our time living together”.

Links: www.samharrisphoto.com