In the 1960s, everything ground to a halt. In France, photography went into a sudden decline and, for many photographers, these were the wilderness years. Publications and exhibitions were increasingly rare and the demand for images drastically declined. The press itself, now seriously under pressure from television (the number of sets in French households already exceeded a million), moved away from humanist photography; it favored a more detached style and a new generation of photographers with a vision that was at odds with the humanists and the narrative reportages of the illustrated press. One sign of this intergenerational transition was the disappearance of the Groupe des XV in 1958 and the birth in 1952 of the Club 30 x 40, made up of passionate young photographers determined to overthrow the prevailing gods and, above all, to promote an auteur photography largely unknown to a market that focused primarily on the commercial and decorative aspects of the art. An entire generation of photographers was consigned to the scrap heap and departed to await better time. The greatest among them were not spared: Willy Ronis took himself off to live in Provence and Doisneau himself was not unaffected. Free from many of his obligations, he was pleased to return to his Parisian flaneries, but these were no solution to his material needs and family concerns: his wife was seriously ill. He found himself forced to take on a number of uninteresting jobs that impeded the realization of his personal projects.

Fortunately. Doisneau’s collaboration with the weekly La Vie Ouvrière continued until 1980. He had many friends there, including the Directors of the CGT, Georges Seguy and Henri Krasucki. The magazine commissioned a series of reportages and a number of photomontages in both black-and-white and color, which were often used for the magazine’s cover. This was something he particulary enjoyed and produced some spectacular results. The famous montage The Hands of the Steel Industry showing hands with the fingers chopped off on the background of a Sollac factory in Moselle, is particularly eloquent.

Since time was now on his side, he made others such as The Tenants House combining a number of shots made earlier in his life to create a veritable synthesis of a particular kind of society. These slices of life offered clues to “an entire city, an entire life, an entire epoch” wrote Albert Plécy. Doisneau returned to this art form with Le Pont des Arts, a jigsaw of the vivid life of this emblematic footbridge; in 1965, his photomontage formed part of an exhibition at the Musee des Arts Decoratifs, shown alongside works by Jean Lattes. Willy Ronis, Daniel Frasnay. and Janine Niepce. In homage to the demolition of Les Hailes de Paris in 1971, he made a similar synthesis of the nocturnal activity of the “belly of Paris. “These technical games and manipulations kept him amused and led him to modify some of his cameras in order to make experiments such as Optical Distortion (a warped Eiffel Tower) or The Corkscrew Couple, which were used in a publicity campaign for the textiles manufacturer Lesor.

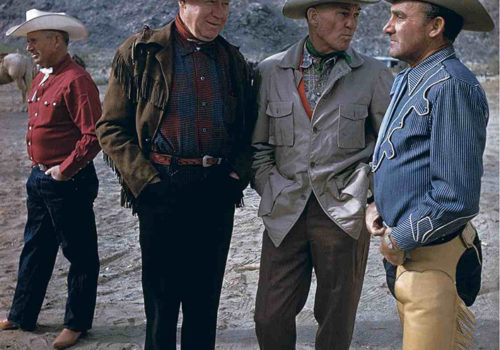

In 1960, Doisneau, the inveterate Parisian, briefly left the capital. His friend Maurice Baquet, who was on a theater tour in the United States, invited Doisneau to join him and there continue their series of cello photos. After much hesitation and the intervention of Charles Rado, who solicited commissions from the magazines Fortune and Life, Doisneau decided to leave for New York. There, he took a series of images that were published in Life, while having the time of his life with Maurice Baquet. He then flew to Palm Spring, a new town constructed in the middle of the desert, made up of golf courses, swimming pools, and villas, and inhabited by a colony of millionaire ,

old-age pensioners. This reportage took the form of slides and Doisneau demonstrated a virtuosity in the use of color that perfectly matched the kitsch aspect of this rather absurd environment.

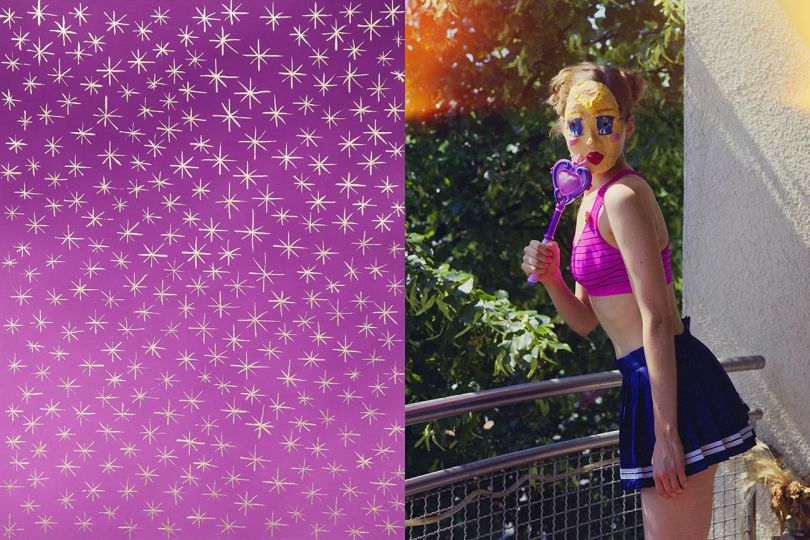

“On building lots next to green spaces, they had built residences that varied between the Swiss chalet and the Chinese pagoda, like so many fantasies and travel memories. Indoors, old couples of excessive wealth were comfortably bored … Swimming pools everywhere of course. But no diving and no splashing. I can remember a melancholy septuagenarian who had realized a lifetime’s dream: after working with four telephones on his desk, he now possessed not one but two swimming pools separated by a mirror. One was for summer, the other for the winter : the latter was part of his living room… Sitting in his armchair before the azure mirror, he was playing, with rubber of bamboo … “

In a world that reflected so little of what he was, Doisneau made a visual travel-diary that dealt harshly with a certain American way of life. These images, whose whereabouts were long unknown have recently been rediscovered in the archives of the magazine Fortune. They are surprising both in their modernity and the critical, ironic scrutiny that he brought to bear on this alien universe. Their uproariously caustic tone reveals a completely new side of Doisneau. The strident colors of his images are sometimes evocative of the paintings of Edward Hopper and prefigure the photos of Martin Parr. After a short stay in Hollywood, where he attempted to photograph Jerry Lewis without notable pleasure, Doisneau was overjoyed to return to Paris.

In contrast with this excursion through the capitalist world, Doisneau also made a trip to the USSR in 1967 at the request of Vie ouvriere to mark the fiftieth anniversary of that country’s existence. But working conditions were very different there and he could not accommodate his art to them. “I would have done better to stay at home … You can’t wander the streets in the USSR.” Doisneau nevertheless brought back some twenty prints that he had contrived to capture between two official visits.

During these slightly lean years, Doisneau nevertheless managed to publish a few books, such as Epouvantables epouvantails (Scary Scarecrows; 1965), a sort of hymn to outsider art, Metiers de tradition (Traditional Trades; 1966), and Témoins de la vie quotidienne (Witnesses of Daily Life; 1971); the last of these was the fruit of an extensive tour around regional museums with Jacques Dubois. More significant was Le Paris de Robert Doisneau et Max-Pol Fouchet, published in 1974: a long voyage through Paris, its signs and tiled shopfronts from the 193os and, in short, the entire signage that punctuates our lives. Doisneau did not greatly like the chaotic layout of the book but it has become a repertory of the many elements even then disappearing from the Parisian cityscape. The very nature of his subjects encouraged him to increase the focal length and stand back further. Consequently; the surroundings take on greater significance in the resulting image. As he said, “I was less close up and there are numerous details in the backgrounds which therefore take on a new importance.

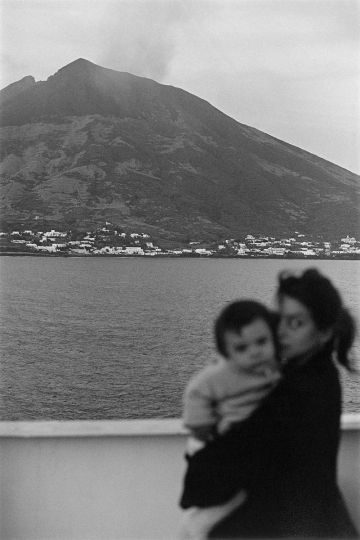

Whether he liked it or not, he had more time on his hands now and this encouraged him to add to the work that he had already begun over the previous few years on Les Hailes. When, in 1967, he learned that the Parisian wholesale food markets were to move to Rungis and that Victor Baltard’s magnificent cast-iron structures were to be demolished, he decided to go there as often as he could, sometimes from three o’clock in the morning, rubbing shoulders in this vast marketplace with the very colorful crowd that inhabited the place. “I had lots of friends there, in that ‘village.’ I was the inoffensive photographer considered a sort of amiable loon … Ah, what solidarity there was among those who worked by night! And I turn and we turn the handle of the barrel organ whence there comes a sad tune perfumed with the celery of Saint-Eustache.”

“In chronological order, I wanted to: faithfully reproduce the outside of things; discover the hidden treasures people trample underfoot every day; make fine slices of time; frequent phenomena; find out what makes some images so endearing …”

In the midst of the noise, smells, and jumble of the market, Doisneau was completely at home and his empathy with people made it easy for him to approach them. Alone or accompanied by his nocturnal brother, Robert Giraud, he captured among the streets and market buildings, from the bistros of Saint-Eustache to those of the Fontaine des Innocents, an entire people who lived by the principles of conviviality and mutual aid. One of his friends, Pierre Delbos, remembers nights spent in the “belly of Paris” with Doisneau. “What surprised me was the way people came up to him; he really had a nose for things, you should have seen the way he looked at them, he loved them!” so Doisneau threw himself into this work knowing that it was merely a matter of time before this entire universe was consigned to oblivion. He continued this campaign until the market buildings were demolished in 1971 and. indeed, beyond that point, by photographing the rebuilding of the “hole” left by the demolition.

Like many of his colleagues, Doisneau found things difficult during the 1960s; work and money were scarce. But in 1970, there were signs of life with the advent of the Rencontres internationales de la photographie d’Arles, founded by Lucien Clergue, Michel Tournier, and Jean-Maurice Rouquette. This now annual event marked the beginning of a new era for photography The recognition of auteur photography became the catalyst for a series of initiatives, such as the founding in Toulouse of the Chateau d’Eau gallery by Jean Dieuzaide, which opened its doors on April 23, 1974 with an exhibition by none other than Robert Doisneau. This superlative exhibition effaced from memory any trace of the one given to him in 1968 by the Bibliotheque Nationale, whose exhibition space was a narrow landing between two stories and where the photographs were hung by being stapled on to pieces of plywood. That show was emblematic of the very limited respect bestowed on photographers at the time. The exhibition in Toulouse marked the start of a new interest in Doisneau, who was the principal guest artist at the Rencontres internationales de la photographie d’Arles the following year, when he charmed his audience by speaking of his spontaneous feelings of love for those he photographed. In the wake of his appearance at Arles, some dozen exhiibitions were immediately on offer, at the Witkin Gallery in New York and others in Brussels, Basel, and Cracow alongside Brassaï, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Jean-Philippe Charbonnier, lzis, and Marc Riboud (1975).

Now that photography was occupying the limelight, the French state moved rather belatedly into action and, in 1978, the ‘\linistry of Culture woke up and established a Fondation nationale de la Photographie at the Chateau Lumiere in Lyons. That same year, Doisneau exhibited at the Musee Nicephore Niepce at Chalon-sur Saône and published two books, La Loire in the Journal (a travel collection edited by Jeanloup Sieff, and L’Enfant et la colombe (Child and Dove), a voyage into the fantastical that Doisneau had begun in 1963; published only in 1978, it won the Prix du livre at Arles the following year.

Thus, by the end of the decade, things were again on the move; there were all kinds of initiatives, and members of the post -war generation of photographers returned to prominence. Moreover, a new generation was discovering a vision of the country and its people along with the charms of a certain kind of nostalgia. In 1975, Claude Nori founded the photographic publishing house Contrejour and, in 1979, definitively re-established the reputation of this most Parisian of photographers with Trois secondes d’eternité (Three Seconds of Eternity), a first survey of his career. this, too, won the Prix du livre at Arles in the year of its publication. A handsome selection of images accompanied by a long text by Doisneau himself, it showed that his pen was as limber and graceful as his photography Still in 1979, the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris exhibited more than 200 Doisneau photographs under the title Paris, les pass ants qui passent (Paris and the Fleeting Passers-by).