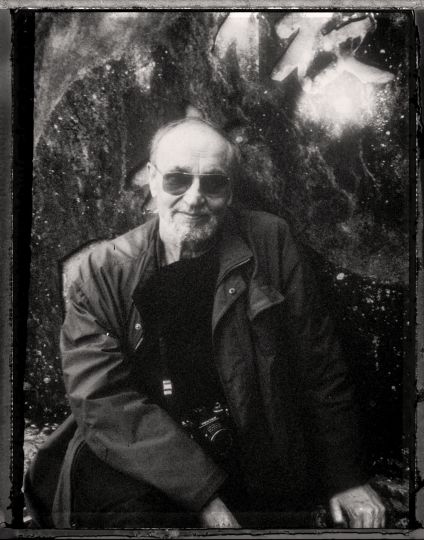

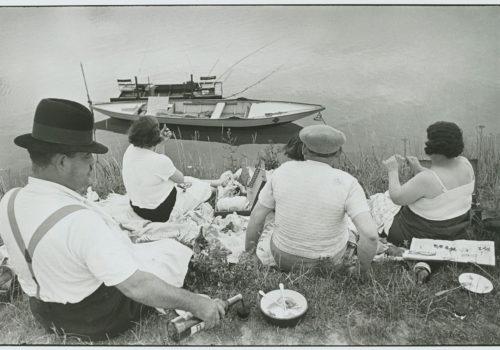

Éditions Delpire is publishing an amazing book dedicated to the career of the famous editor Robert Delpire and to his relationships to his contributors. We are offering a series of texts he wrote. Today, The Eye of Photography is publishing an interview of the French editor about Henri Cartier-Bresson by Philippe Séclier.

When and under what circumstances did you meet Henri Cartier-Bresson for the first time? What was your first impression? What kind of man was he?

I met him in 1951. He was coming back from a three year trek in the Far East. The previous year, I had started to publish an illustrated magazine for doctors. Naturally, I went to the first office of Magnum Photos to present NEUF to these photographers whose reputation was going to sky rocket. I found three simple, friendly men: Chim, Capa, and Cartier-Bresson. They were as different from each other as possible, restless, full of projects. I was content (and honored) that they accepted me and adopted me as a potential editor. I was twenty-five. Henri was like I always knew him, with a superb presence and glowing intelligence.

How did you work with him?

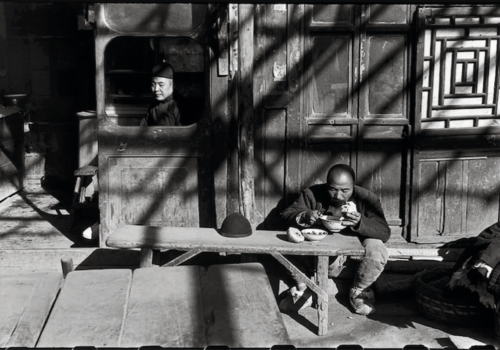

We got on very well with each other. The subjects came about naturally, one after the other. Bali, China, and the others. As for how we worked, it was quite simple, but very early on we made a rule. In case of a disagreement, if it dealt with the choice of a photograph, Henri would decide. He was the author. If the disagreement dealt with the graphics, the sequencing, even the shape of the book, Henri trusted me. It was a system where responsibilities were shared, avoiding long discussions, This rule, was strictly observed.

How many pieces of his did you publish? And do you have a soft spot for one of them?

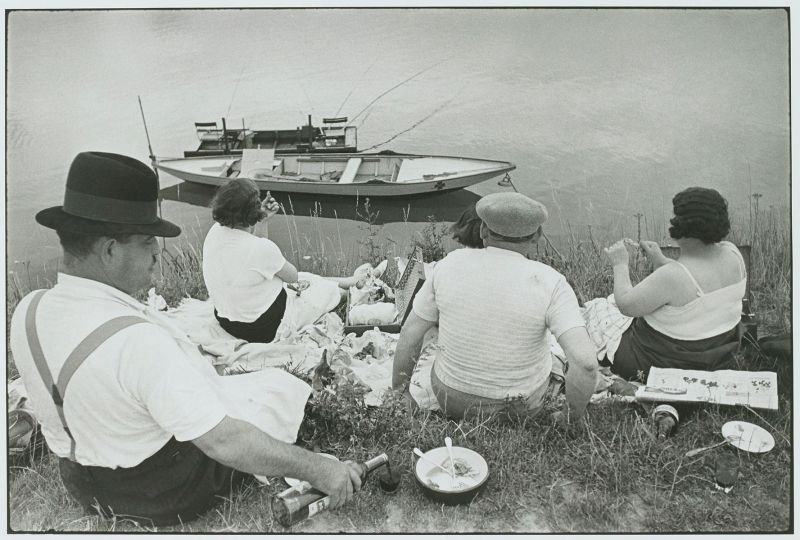

I didn’t count. At least a dozen, and a certain number of albums that I set up which other editors published. Which do I prefer? Probably the massive Cartier-Bresson Photographe that we just reprinted for the eighth time. To me, it seemed like the book made an account of the work, soberly, effectively.

Have you thought, if only once, and even if he forbade it, of reframing one or several of his photos? If only just to see?

To see what? To verify that his framing is impeccable?

You didn’t publish Images à la sauvette, which included the famous text “The Decisive Moment”, and which is one of his most well-known books. Is that not frustrating for an editor?

No, there is nothing frustrating there. Tériade is someone whom I respect, as an editor and a critic. For me, his merit was in being the first to consider a great photographer like an equal of the great painters. The format of Images à la sauvette, which was from Verve, the cover that he asked of Matisse clearly showed his intention. As for the text on “the decisive moment”, it’s a part of the international photographic heritage.

Are there photographs of Cartier-Bresson that you regret not having published?

No. When I prepared Flagrants Délits, I saw all the archived contact sheets at Magnum. I believe that I knew almost all the images, and no, I don’t have the slightest regret. In the book that we’re are preparing on landscapes, there are a few previously unpublished photographs. There will always be some. The work is too vast to not still make discoveries.

Among all the photographers whom you have edited, which one is the closest to Cartier-Bresson?

He influenced two or three generations of photographers, which is nothing shocking. Rarely did a man, like him, open a lane, define a means of expression, demonstrate an ethic. So it makes sense that he was an example for so many reporters. Pointing out only one wouldn’t make a lot of sense.

For many photographers, he was the absolute reference, a sort of landmark. For you, too?

Evidently. The absolute reference, but for a certain type of image, for reporting. He is the perfect example of an exceptional talent, benefiting a conception of man and the world, an instinct constantly in balance with a sharp intelligence and a culture, just as much political as pictorial and literary. I know I’m falling into the superlative, but how could one do otherwise?

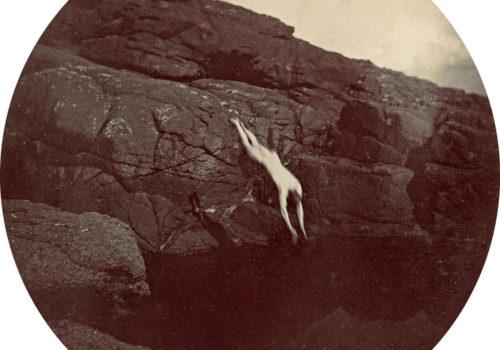

From 1970 on, Cartier-Bresson dedicated himself to drawing and painting. How do you view his work?

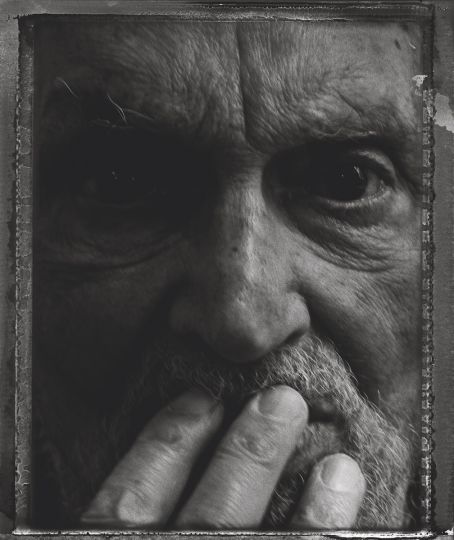

I find it very courageous that an artist, at the peak of his career, at the height of his notoriety, would take the risk of putting himself back into question and of facing the public, specialists, critiques. We know now that he drew, that his portraits, his landscapes, his nudes exist.

Since he still continued to make some, what can you say of his most recent photos?

He really did make very few of them. A sketchbook replaced the Leica slung over his shoulder. He photographed his family, his friends, some portraits, some landscapes. His eye didn’t change. It was the need to accumulate disappearing images.

If you had to conserve one sole image from Cartier-Bresson’s work in the corner of your memory, what would it be?

For almost forty years I’ve been living with his photography which I’ve selected, I’ve laid out, I’ve put on the wall or on the page, I’ve filmed or I’ve printed. There are clearly images that I prefer to others. But finding just one wouldn’t make much sense.

Can you say, though your modesty would have to suffer, that you were the eye of “the eye of the century”?

No, I can’t say that. “The eye of the century”, as you called him, is his. Not mine. A photographer is an artist. An editor is an artisan. His only advantage is not having lived the photos. He did not know the fatigue, the sweat, occasionally the fear. He can, therefore, judge the quality of a photograph more objectively and more serenely. But sometimes that’s not even true.

Interview by Philippe Séclier

Philippe Séclier is a journalist and photography exhibition curator. He lives and works in Paris.

C’est de voir qu’il s’agit…

Published by Éditions Delpire

35€