One of the most striking exhibition at the Rencontres d’Arles this year was the presentation coproduced with Photo Elysée of Debi Cornwall’s exploration of the staging of militarized power and what it entails to be a « model citizen » in such societies. Zoé Isle de Beauchaine met with the photographer at Espace Monoprix.

Zoé Isle de Beauchaine: This exhibition and the book that comes with it (published in English and in French by Radius Books and Textuel) follow the Prix Élysée that you won in 2023. How did the project come about ?

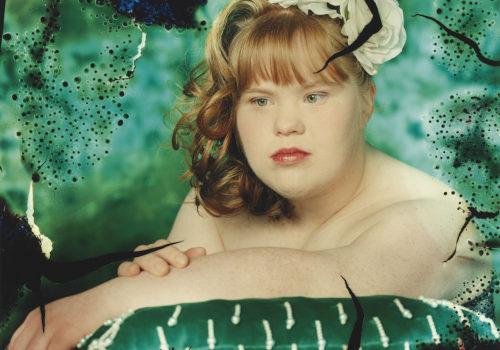

Debi Cornwall: The idea for Model Citizens arose from my 2020 book Necessary Fictions, which is also on view in this exhibition. I’ve been interested in the staging of American power in all of my works and increasingly in the performance of citizenship. These are two sides of the same coin. My focus traditionally has been on how state power works on us and I’m now thinking about how performative fictions manage difficult truths in civil society, for example in museum installations and in social life as well as in the Rally series : we are not just passive beings who consume governmental propaganda. We are also using fictions, stage plays, simulation for our own ends to make sense of our different realities.

You come from a background as a lawyer specialising in civil rights and turned to a photography ten years ago. Did you embrace a conceptual documentary practice focusing on these questions from the beginning ?

D.C : Yes and no. In university I took some photography classes. I interned for Mary Ellen Mark and thought I would like to be a social documentary photographer. This was in the mid-90s. Analog, black and white… I didn’t know what else a practice might look like. However I didn’t get the newspaper job I applied for when I graduated from college so life took a very different turn. But when I came back after having practiced as a lawyer who used individual cases as a means to expose systemic injustice, that legal training, that way of working, researching and thinking, very much came to inform the way that I made visual work as well as the way I think about what images can accomplish, the kinds of conversations they can spark.

The exhibition shows different sites of training for military purposes, from wars in the Middle East to the United States Border Patrol Academy in New Mexico. Could you tell us more about these ?

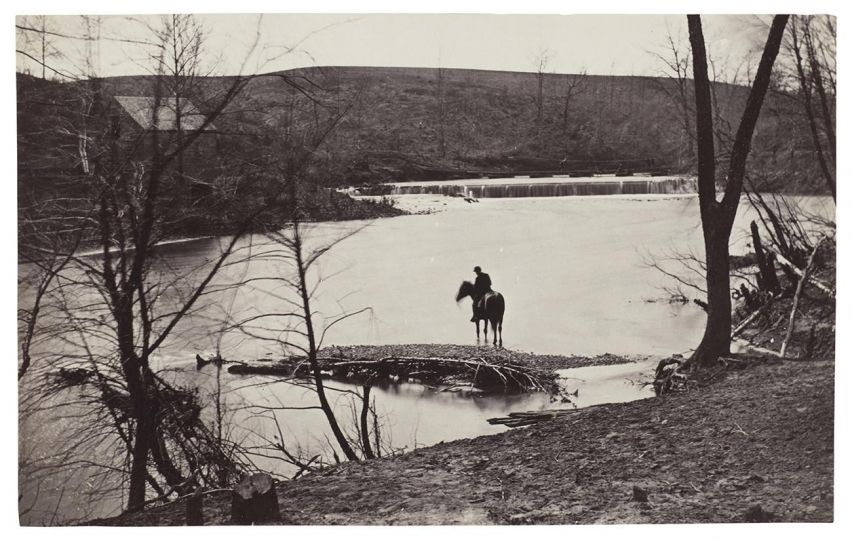

D.C : The first of these venues is from Necessary Fictions, my 2020 photobook where I documented the fictional country of Atropia, which exists only on American military bases across the country. Mock Afghan and Iraqi village sets are constructed to evoke the sights, the sounds and even the smells of the original villages, for soldiers preparing to deploy. These sites are also populated by civilians who act as “cultural role players. » They are often naturalized American citizens, they are fluent in Arabic and and other relevant languages. They have come to the United States, some of them even fleeing war, only to put on costumes and perform versions of their past lives in the service of the U.S. military. And this is something they are getting paid for, it’s a job. Similarly, at the mock border sites of the United States Border Patrol Academy, border patrol agents take part in realistic immersive scenarios to give them a memory sense for what to do when they deploy on the actual border: how to track, apprehend, and decide whether to use deadly force against people they refer to as « illegal aliens ». These latter are enacted by hired actors, often Hispanic Americans, naturalized citizens from places like Mexico who are enacting the « bad citizen », the « non-citizen », the threat.

Your work teaches us to look more closely at the fine line between reality and fiction.

D.C : In the exhibition, the first two walls and the entrance are meant to disorient you, in a way that invites your curiosity and to look very closely at what’s in the pictures. It’s a practice of juxtaposing different things in order to invite the viewer to figure out what’s happening here. With journalism now, we often see the same kind of pictures, and whether it’s of the front lines of war or the border, we think we’ve seen it. We don’t look. It becomes devoid of meaning. By using fiction, I’m hoping to get people to think differently about the reality, look more critically at what we’re being shown.

After your first book, you are now interested in the performance of American citizenship. What led you there ?

D.C : This experience of looking at military sites and writing about the blurring of fact and fiction in a militarized country for Necessary Fictions made me realize that these « sites of exception » actually highlight the truth about our culture. We think about these sites as relating to war overseas, but they have become a multi-million-dollar business and are embedded across the United States. What does it mean to normalize the fictional scenarios that play out in such sites? This is the point of my practice, to make us see the metaphorical air we are breathing. All of that got me thinking about the performance, not only how official fictions work but how we enact them, and how civil society stages American-ness. Not only the military and the Border Patrol Academy, but also American historical museums invariably staging Americans as heroic victors and as victims, as well as the political rallies I documented in Model Citizens.

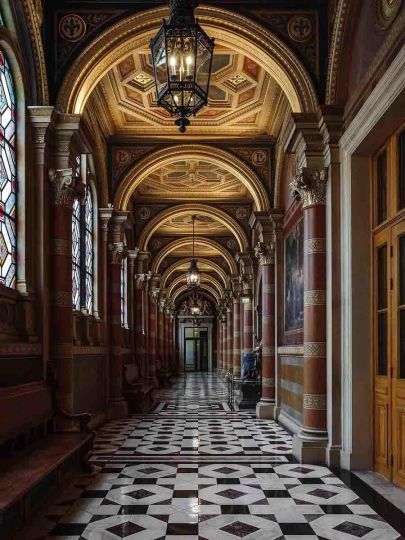

What drew you to historical museums ?

D.C : I’m interested in how museums try to draw in visitors by creating immersive environments designed to bring history to life. I’m drawn to the trompe l’oeil and the sometimes absurd unintended effects. Look at this image, “9/11-World Trade Center Installation”: on museum walls, a foundphotograph of the Twin Towers exploding has been enlarged and installed around corners in a museum space. It’s hard to orient oneself, but you can see a pipe in the ceiling above the wallpaper. This is a case where the drive toward realism perhaps went a little too far. Or if you take the Colonel Mitchell Paige diorama from the World War II Museum in Eldridge, Pennsylvania. The exhibit honors a local boy who served in WWII with valor. In doing so, they turned him into Rambo, the Vietnam War veteran movie character from the 1980s movies. We can’t help but resort to Hollywood in memorializing and honoring our soldiers. It’s not coincidental. This picture is just on the other side of a wall from my experimental film that incorporates Hollywood material.

The film closing the exhibition is untitled Pineland/Hollywood. You tell the story of a traffic stop in a mashup of Hollywood action and war movies.

D.C : The story is a case study, an encapsulated version of the larger questions that I’m dealing with. Pineland/Hollywood is about a traffic stop in which distinguishing fact from fiction became the difference between life and death. As part of my research, I always steep myself in cultural representations of what I’m looking at. I was watching a lot of war movies when working on this project. Amongst them was Bridge on the River Kwai. In one scene where the protagonist is walking into a military base and get suddenly attacked, thrown to the ground by a man with a knife. A supervisor jumps in, revealing that the attacker was a trainee in the middle of an exercise. I had this sudden flash of illumination : Might it be possible to try to tell the Pineland story using Hollywood film clips? And what other layer might that add? Ultimately, Pineland/Hollywood uses 500 fair-use clips from 200 movies in 10 minutes to tell one story. And there’s a revelation at the end that I will not disclose to the onlookers, but, like all of my work, it rewards attention.

Model Citizens / Citoyens Modèles is available in bookshops and online. It is published in English by Radius books (here) and in French by Éditions Textuel (here).

Debi Cornwall – Citoyens modèles

Curators: Nathalie Herschdorfer andLydia Dorner

A coproduction with Photo Elysée

Until September 29th

Les Rencontres d’Arles

Photo Elysée